WRB—Apr. 20, 2024

“the surprise of middle age”

Are the Managing Editors the only ones who think that literary criticism, looking at language nuances, is useful?

N.B.:

“New York’s Hottest Club Is a Literary Event,” but in D.C. the place to be is the next WRB x Liberties salon, which will take place on May 18. If you would like to come discuss the topic “Should you like your friends?” please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

In Minor Literature[s], an excerpt from a collection of essays by Michel Butor (Selected Essays, translated by Mathilde Merouani, 2022):

The true writer is the person who cannot stand to have certain aspects of reality be talked about so little or so poorly, who feels obligated to draw attention to some of these aspects in a manner they hope definitive. Not that the writer imagines in the least that once they have addressed these aspects there will no longer be any need to talk about them—on the contrary. What the writer wants is for the mind to be forever alert. In the same way, the most useful critic is the person who cannot stand to have certain books, paintings or pieces of music be talked about so little or so poorly, and the sense of obligation is as pressing in the area of criticism as in any other.

The critic is outraged: “How can you not see, not love, not feel the difference, not understand how much this is what might help you?”

In Dirt, Naomi Kanakia on the absence of money from contemporary novels:

It is suggestive that it’s in literary fiction where money-talk is the most taboo. Commercial novels frequently touch on money and occupation—it’s a main driver of conflict in romance and crime novels in particular. But literary fiction is largely removed from mass opinion and is shaped by a small number of critics, editors, and agents, mostly from elite backgrounds themselves. It’s certainly possible that part of the class replication strategy for upper- and upper-middle-class literati involves suppressing mention of money in literature. If so, I can only lament the harm this suppression does to the work in question.

I’m not particularly moved by considerations of fairness—most literary writers come from privileged backgrounds. That’s true today, and it was true in Austen’s time as well, and I don’t see it ever changing (even in the Soviet Union, it was rare for a successful writer to be from a peasant or proletarian background). But I do think this silence about money seriously harms the work on an artistic level.

[Jane Austen’s two most “political” novels—Mansfield Park and Persuasion—add to the money talk a focus on where the money comes from; Sir Thomas’ need to attend to his slave plantation makes possible various moral disasters at home, and the men of the Royal Navy, who make their money by actually doing something valuable, come off much more favorably than titled aristocrats like Sir Walter, who don’t and look down on those who do. This element still exists in contemporary novels, even if in the attenuated form of saying what characters’ jobs are. But without the explicit discussion of income it loses its punch, since to be dedicated to “the amorous effects of ‘brass,’” as Auden put it, requires some specifics. —Steve]

Two in The New Yorker:

Kyle Chayka on Byung-Chul Han:

In Non-things (2022), Han argues that online we encounter a glut of information—i.e., non-things—that distracts us from having experiences with objects in the world: “The digital screen determines our experience of the world and shields us from reality.” The best way to read Han is similar to the best way of reading the Bible: flip through, find an evocative line, and proceed from there. Each sentence is a microcosm of the book, and each book is a microcosm of the oeuvre, thus the reader need not delve too deep to get the point. “The smartphone is a mobile labor camp in which we voluntarily intern ourselves,” Han writes in Non-things. Spicy! It is a koan to meditate upon, and a description that immediately makes one hate oneself for staring at a screen. I kept reading because I felt like I had to, in case Han might be able to offer me some salvation.

[I am tired of reading sentences like “We are so stimulated, chiefly by the Internet, that we paradoxically cannot feel or comprehend much of anything.” It is a shabby use of the first-person plural to imply that the reader suffers from the same failings and complicities as the writer. Accuse yourself directly; accuse me directly; accuse the world directly; but do not suggest, as if I the reader were some old friend of yours, that you know and share my secret faults. That they exist, I grant you; that the buck-passing generalities of the first-person plural will identify them, I do not.

Putting together this newsletter requires, of course, significant time spent on the internet—you may think of me as a pearl diver working in untreated sewage—and, despite that, I am still confident in my abilities to feel and comprehend. (Maybe it’s all the uninterrupted time I spend reading books and watching movies.) To be clear, I hardly think the internet is an unalloyed good and would love to see its influence reduced (you should keep reading the WRB, though). That said, something like “access to smartphones in schools is hindering learning” is one kind of problem, and “you, a grown adult, cannot sit down and watch a movie all the way through without checking your phone six times” is a different kind of problem. You can do something about the latter right now. Writing pieces about societal issues clearly motivated by your own failure to handle technology responsibly (as is commonly seen) is well and good, but it’s orthogonal to changing your own life. If thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out—don’t drag me into it. —Steve]

In First Things, Matthew Gasda reviews Han’s latest (The Crisis of Narration, translated by Daniel Steuer, April 1):

Whereas narratives have a “wondrous and mysterious” quality, there is something frantic about the data pouring out of our screens: charts and infographics, advertisements and commercials. Our information society lives in an “age of heightened mental tension”: constantly stimulated, constantly expecting surprise, constantly fragmented. Phono sapiens may become terrified of climate change, political extremism, or microplastics; he may compulsively bet on stocks and games; he may be addicted to dating apps; or all of the above. In any case, he is stuck in an information loop without the possibility of closure.

Alex Ross on noise:

We humans have a high tolerance for noise, despite our ambivalence. In some way, we seem to require it. Other species feel differently about the never-ending sonic havoc of the Anthropocene. Caspar Henderson, in A Book of Noises: Notes on the Auraculous (2023), points out that when our species stayed mostly indoors during the early months of the covid pandemic the animal world reacted with apparent relief: “Birdsongs regained qualities that had last been recorded decades before, when cities were quieter. The white-crowned sparrows, for instance, extended their sounds back down into lower frequencies . . . and their songs became richer, fuller and more complex.” Birds also sang more softly: they “had been ‘shouting,’ just as people raise their voices on a construction site or at a noisy party.” Their stress levels likely declined. Noise is another dimension of humanity’s ruination of the natural world.

[Echoes of Screwtape’s ersatz Futurism: “Noise, the grand dynamism, the audible expression of all that is exultant, ruthless, and virile—Noise which alone defends us from silly qualms, despairing scruples, and impossible desires.” And from the subtleties of birdsong, even if humanity, as Philomela could tell you, brings its own violence into those sounds. —Steve]

In Tablet, Edward Serotta visits Paul Celan’s hometown of Chernivtsi:

Thousands of research papers have been written on Celan. German composers and artists have drawn from his work, and German academics have mined one incident after another in Celan’s life to dissect it. Just google “Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland” and you’ll find books, films, theater pieces, panel discussions, and works of art—by the thousands. And “Todesfuge” overshadows everything he would write later.

Countless school classes in Germany recite it each year. For instance: In February 1995 I sat in the audience of a high school auditorium in Berlin’s Köpenick, where nine girls sat on the stage and recited the poem to a packed hall of students and family members. A year later I was in a Waldorfschule in Bremen, where 30 high school seniors took to the stage and with a choir master in front of them, yelled the poem, in perfect precision, at the top of their lungs, to devastating effect.

[We linked to an earlier installment of Serotta mixing travel literature from Ukraine with appreciation of a writer in WRB—Mar. 2, 2024.]

Two in our sister publication on the Thames: first, Terry Eagleton on the origins and development of culture:

Both types of culture are currently under threat from different kinds of leveling. Thinking about aesthetic culture is increasingly shaped by the commodity form, which elides all distinctions and equalizes all values. In some postmodern circles, this is celebrated as anti-elitist. But distinctions of value are a routine part of life, if not between Dryden and Pope then between Morrissey and Liam Gallagher. In this respect, anti-elitists who like to see themselves as close to common life are deluded. At the same time, cultures in the sense of distinctive forms of life are leveled by advanced capitalism, as every hairdressing salon and Korean restaurant on the planet comes to look like every other, despite the prattle about difference and diversity. In an era when the culture industry’s power is at its most formidable, culture in both of its main senses is being pitched into crisis.

Reviews:

Second, Freya Johnston reviews a book about Dr. Johnson’s criticism (The Literary Criticism of Samuel Johnson: Forms of Artistry and Thought, by Philip Smallwood, 2023):

Here, as always, Johnson has the varying demands and interests of his audience in mind. The critic’s task, like the editor’s, is not merely to single out beauties and faults, to praise or to blame, but to disentangle complications, a task in which he or she will always need the help of other readers. The mind of the literary critic can therefore be neither self-sufficient nor conclusive, but must remain amenable to change and suspicious of “the cant of those who judge by principles rather than perception.”

In Literary Matters, Lee Oser reviews a collection of William H. Pritchard’s writing (Ear Training: Literary Essays, 2023):

Pritchard is similarly wedded to his subjectivity: his idea of tone conveys objective value only when it captures feeling and emotions that are rooted in nature. Otherwise, it is impressionistic and hierophantic (a priest of criticism in his Amherst temple), or, as Pritchard rightly acknowledges, “mysterious.” When his students have trouble communicating Shakespeare’s aural power, he reflects on their experience: “‘I can hear it in class when you read it aloud,’” said another student, the mysterious “it” being (perhaps) the pace, the swing, the tonal achievement and human feel of a passage.” Mind you, I am not dismissing these terms as meaningless. In the classroom of such a gifted professor, they may well be edifying. But there may be good reason why students find them elusive. Shakespeare was trained as a rhetorician, and none of the Greek or Latin rhetoricians, nor their Elizabethan counterparts, wrote this way about their art.

In The New Criterion, D. J. Taylor reviews a book on the poetry of World War I (Muse of Fire: World War I as Seen Through the Lives of the Soldier Poets, by Michael Korda, April 16):

If the question of how Brooke might have ended up had he survived the war is unanswerable, then it can be safely predicted that he would not have written many more poems like “The Soldier” (“If I should die, think only this of me:/ That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is for ever England”). He might, of course, simply have taken a job at headquarters and peddled the official line. In the end, the only thing that can be said truthfully about Great War poetry en masse is that there comes a moment when, however incrementally, it begins to lose its abstraction. Comparing Brooke’s “If I should die, think only this of me” with Sassoon, the Georgian critic Edward Shanks suggested that “Brooke’s subject is the impact made on his mind by the imagined possibility of death in certain circumstances”; Sassoon, alternatively, is “moved by something a great deal more definite.” He was indeed, and the latter stages of Muse of Fire are an eloquent testimony to all that he, and others like him, had to endure.

N.B. (cont.):

On the work of repairing the undersea cables that bring you the internet: “People will sometimes note that these are the largest construction projects humanity has ever built or sum up a decades-long resume by saying they’ve laid enough cable to circle the planet six times.”

Inside the book conservation lab at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A profile of Rusty Foster, of Today in Tabs. [One of my best friends in high school lived—well, he still does—on Long Island (the one in Maine, not the one you’re thinking of) and so I feel obligated to boo Peaks. (Really though, Peaks Island is nice.) —Steve]

New issues:

First Things May 2024 [As linked to above.]

The New Criterion Volume 42, Number 9 / May 2024 [As linked to above.]

Local:

The local Post solicits reader input on the best dive bar in the D.C. area.

A ranking of government agency logos.

The Friends of Southwest Library book sale will take place at said library today from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Nicolette Polek will discuss her new novel (Bitter Water Opera, April 16) with Maud Casey at Politics and Prose tomorrow, April 21, at 5 p.m.

The Capital Rare Book Fair will take place at the University Club from Friday, May 3 to Sunday, May 5.

Poem:

“Object Permanence” by Nicole Sealey

[For John]

We wake as if surprised the other is still there,

each petting the sheet to be sure.How we have managed our way

to this bed—beholden to heat like dawnindebted to light. Though we’re not so self-

important as to think everythinghas led to this, everything has led to this.

There’s a name for the animallove makes us of—named, I think,

like rain, for the sound it makes.You are the animal after whom other animals

are named. Until there’s none left to laugh,days will start with the same startle

and end with caterpillars gorged on milkweed.O, how we entertain the angels

with our brief animation. O,how I’ll miss you when we’re dead.

[This poem is from Sealey’s Ordinary Beast (2017), her first full-length collection.

There’s so much about this poem that’s lovely: the strange auditory image we get when the speaker tells us rain is named . . . for the sound it makes, for one. But I also just appreciate how Sealey approaches love in all its strangeness: the animal / love makes of us. And one of the ways that love makes us strange, Sealey shows, is how, at times, the experience of it runs against what we know to be rational. The lovers give into it even as they cling to their sense of themselves as rational:

. . . Though we’re not so self-

important as to think everythinghas led to this, everything has led to this.

I love those lines so much: how sure and in control the beginning of it sounds, and the sudden surrender that happens with the second repetition of everything has led to this. And that line admitting this love’s contra-rational centrality fits in so well with the diction of this poem, with its ecstatic Os and lines like beholden to heat like dawn / indebted to light. It all gives the poem this golden, abundant feel. But it isn’t overwrought; there’s such a simplicity to the opening image—the same startle each day when the lovers wake in the morning and look at each other with such appreciation that it’s almost like surprise—and to the last line, too. The enjambment that leads into that last line is set-up so well, with the second ecstatic O just dangling there, right before the speaker’s acknowledgement that the ecstasy of their love, its warmth, is temporary. But because it’s stated so earnestly—how I’ll miss you—that acknowledgement reinforces, rather than undermines, everything that comes before it. —Julia]

Upcoming books:

April 23 | HarperOne

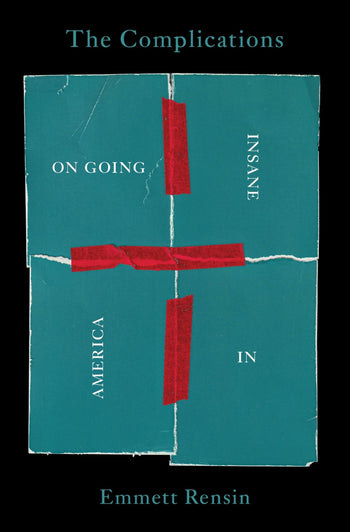

The Complications: On Going Insane in America

by Emmett Rensin

From the publisher: Going beyond the usual peans against “stigma” and for “understanding”, Rensin confronts the dysfunction in current mental health narratives, contrasting what he calls mental illness “high culture”—in which we affirm the prevalence of anxiety and encourage regular therapy, insisting that the “mentally ill” aren’t dangerous or even weird—with even progressive society’s inability to contend with people with more severe forms of mental illness: those people we pass on the street talking to themselves, those caught in a loop between hospitals and prisons, or even those who we cannot tolerate in our own schools, offices, and lives, including himself.

With raw honesty, Rensin invites us into every aspect of his life, from what it’s like see four different psychiatrists in one year and the nature of psychotic breaks to a harrowing diary that logs exactly what happens when he stops taking his medication and the unexpected kinship he discovers with an incarcerated spree killer with schizophrenia. Going beyond pure memoir, he reflects on the uncertain “science” of diagnosis, the nature of art about and by the insane, political activism, and the history of madness, from the asylum to the academy.

Also out Tuesday:

Coffee House Press: Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other by Danielle Dutton

Knopf: Lucky by Jane Smiley

Pantheon: Reboot by Justin Taylor

What we’re reading:

Steve read more of The Cromwellian Protectorate by Barry Coward (2002) and, relatedly, read Marvell’s elegy for Cromwell and three articles about it (“Credible Praise: Marvell’s Dilemma in His Elegy on Oliver Cromwell,” by Stephen Szilagyi, 1986; “‘I Saw Him Dead’: Marvell’s Elegy for Cromwell,” by Ashley Marshall, 2006 [The best of the three on account of its willingness to ask the most questions about the poem’s connection to the political situation at the time. —Steve]; and “Love, Chaos, and Marvell’s Elegy for Cromwell,” by William M. Russell, 2010).

Julia’s mostly just been reading Tess Gallagher’s poetry. [Her poems are very strange. I’m still trying to figure out what to think about them. But I love Portable Kisses (1996), which is just a collection of weird poems about kissing. Gallagher: Ideally, a reader should finish this book, then find someone to kiss. This is also the ideal end of reading the WRB poetry column. —Julia]

Critical notes:

Did Willoughby really ever like her? It turns out this is sort of the wrong question. He actually did really like Marianne, he’s just a very unstable person. He’ll flirt with you today, and if tomorrow he’s more worried about his financial situation, he’ll go off to marry a rich woman. The day after that, now that he’s financially stable, he’ll regret trapping himself in a comfortable but loveless marriage. And so on and so on.

So the coordination problem here is not so much about identifying a shared feeling—it’s about identifying whether that feeling, or whatever you want to call it, will cash out in a way that is compatible with your own understanding. Liking the same poets is not a reliable indicator of this, as people continue to discover today.

[Going to bring back the WRB Classifieds, but the only information those submitting personal ads will be allowed to include is which poets they like. —Steve]

The surprise of middle age, and the terror of it, is how much of a person’s fate can boil down to one misjudgment.

Such as? What in particular should the young know? If you marry badly—or marry at all, when it isn’t for you—don’t assume the damage is recoverable.

“Repressive forces don’t stop people from expressing themselves,” wrote the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze in Negotiations (1972–90), “but rather force them to express themselves.” Wiki Aesthetic Fandoms offers an escape route from the self in self-expression. Instead they hijack and remix premade identities, working via temporary, contingent solidarities that might as well have come from reading Judith Butler, Denise Riley, or Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.