WRB—April 12, 2023

“very ticked off and in a hurry”

I’m in a place where I’m trying to honor my needs and act in alignment with what feels right within the scope of my life, and I’m afraid the WRB doesn’t seem to fit in that framework. I can no longer hold the emotional space you’ve wanted me to, and think the support you need is beyond the scope of what a Managing Editor can offer.

Links:

“Many of his misdeeds were a matter of record before he ever stepped foot in Coquille. And yet Walter continued to operate with impunity, charging as much as $1,000 a day as a consultant. America’s fragmented criminal-justice system allowed him to commit perjury in one state and move on to the next. Journalists laundered his reputation in TV shows and books. Parents desperate for closure in the unsolved murder of a son or daughter clamored for his aid. Then there was Walter’s own pathology. He so fully inhabited the role of celebrated criminal profiler he appeared to forget he was pulling a con at all.” Fun crime story by David Gauvey Herbert at NY Mag.

Note from Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr. for The Point on higher education:

Today, there is a resurgence of discussion-based courses like Great Questions at community colleges, standing in stark contrast to the apparent doom and gloom of the humanities in the Ivy League. … We must encourage community college leaders to grow and sustain the humanities programs under their protection, many of which have been seeded by private funding; the future of liberal education may depend upon it. Indeed, despite the dire reports of the state of the humanities, there is a humanistic revival in higher education underway—it’s just happening where few commentators think to look. Community colleges might very well be the best place for this revival.

Joey Keegin on not doing much, birdwatching, and punk rock:

Of course, not all useless activity is actually good. Binge-watching television, being hooked on drugs, or spending one’s day doing nothing but eating are useless activities, to be sure. But truly splendid uselessness nourishes and elevates us spiritually, rather than simply providing a rush of mental or bodily pleasure. The output is always more than the input: the contemplation of nature, the joy of music-making, and even the study of mathematics can be rich and ennobling activities that, while also being pleasurable, reward the intellect and the soul.

At Quillette, Anthony Egan on Kazuo Ishiguro and the uncertain spirit of the age:

In fact, almost all of Ishiguro’s novels depict characters who are, themselves, at least minimally uncanny. His butlers act like robots, his robots act like butlers. His clones act like artists, his artists act like clones. Almost everyone wears an emotional mask in circumstances when soulful self-exposure is the needful thing. All perform their roles according to narrow expectations, all exonerate their prior moral failures by reference to the indelibility of these roles, and all are afraid of violating the taboos that negatively structure their insular habitats. Their outward actions seldom correspond to their inward actions—for their lives are lived as performances calculated to gain the admiration of an imaginary consensus.

Two from the new Liberties, which is blue:

Alfred Brendel on Goethe and Beethoven: “In humor, Beethoven has a marked advantage. Goethe, it is said, possessed a brilliant skill in reciting comic texts, but he was not a humorist and he did not want to be one. Can you imagine Goethe laughing?” [Cf. the first item in Critical notes from WRB Mar. 18, 2023. —Chris]

And Celeste Marcus on what makes a good painting:

A painting is good because of the colors and the forms that make it up. This is as obvious as it is shocking. And it is not “formalism” to say so. For a lover of paintings, for someone who has achieved an occasional moment of transcendence before a canvas, it may seem heretical or idiotic to point this out, the way that it is heretical or idiotic to point out that a book is simply a mass of typed pages or that a person is merely a mass of cells. But respect for the tactility and the materials of paintings is essential to a substantive appreciation of them. If there is soulfulness in a painting, it was put there by a paintbrush. This is so regardless of its subject or its subjectlessness. Can Rembrandt’s Biblical etchings, or Poussin’s mythological paintings, or Hals’ group portraits, be appreciated without reference to the narrative that they present? I think so. Such a distillation of attention must be possible, if they are to be viewed as art. Extra-aesthetic meanings may abound in a picture, but they have no bearing on the painting’s artistic quality.

Two from the new First Things, which is green:

Ben and Jenna Storey write about reasons you might fall in love:

When we read classic literature with our students, love-at-first-sight stories appear everywhere. Students usually find such episodes bizarre and dismiss the characters in them as foolish. They bring up stories of friends whose lives were derailed by drunken hookups, roommates who let high-school sweethearts drag them down, or that dude down the hall who can’t get over some pointless infatuation. But such judgments often miss the mark—for it is frequently the most capable characters who are susceptible to this supposed weakness. Authors such as Dante and Plato tell of sudden encounters with beauty that cause people of great intelligence to change the course of their lives.

Reviews:

The other one from the new First Things:

And Phil Jeffery reviews the book out last fall about McKinsey & Co. (When McKinsey Comes to Town: The Hidden Influence of the World’s Most Powerful Consulting Firm, October):

Public-sector clients seem blinded by their faith that, no matter what the job is, someone who works for a big-name private company will do it more efficiently than an anonymous civil servant can. Better to pay a well-credentialed “business expert” (or several of them) six figures than to have an uncredentialed government worker do the same work for much less. This mirrors the apparent contempt private-sector clients have for lower-level workers in their own organizations. The consultants come in to fire people, to replace people, to shuffle around risk, but above all to embody an idea: There’s a certain type of worker we regard as extraneous no matter what he does, and another type we take to be superior no matter what he does.

For Tablet, David Mikics reviews Benjamin Balint’s new book about a “writer, artist, and idiosyncratic dreamer” (Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History, April):

Hints of Schulz’s masochism appear in his stories. His women are slender, imperious, and aloof, and they delight in teasing the men, especially Jakub, the father of the youthful narrator Jozsef, who stands in for Schulz. The father, a cloth merchant, becomes increasingly strange, obsessed by his recondite scholarly pursuits. Spindly and half-alive, wriggling under his desk lamp, in the end he turns into a cockroach, “merg[ing] completely with that uncanny black tribe.” He becomes a puny nightmare grotesque, a mere toy for his son’s imagination to play with.

In a 1935 essay Schulz compared his first book to Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers, which weaves biblical narrative together with “the timeless myths of Babylon and Egypt.” Schulz said that his own work, far more modest than Mann’s gargantuan, labyrinthine novel, “follows the spiritual family tree down to those depths where it merges into mythology, to be lost in the mutterings of mythological delirium.”

For Full Stop, Eliza Browning reviews two books out this spring by Brian Dillon (Affinities: On Art and Fascination, April) and A. V. Marraccini (We the Parasites, February):

In his recent book Professing Criticism, John Guillory suggests that literary criticism has largely become a product of academic circles rather than aimed at a general public. In order to survive, new forms of criticism have increasingly moved toward a critical/creative mode exemplified in personal essays that meld traditional forms of criticism with autobiography. Dillon and Marraccini take this a step further, suggesting that criticism thrives off personal attachments to art rather than detached, analytic research, and must encompass the individualized emotional connections formed by viewers. Both Dillon’s affinities and Marraccini’s parasitic criticism thus become a phenomenological immersion rooted in embodying the art both writers encounter, resulting in an affective emotional experience that extends to their readers. The authors’ own genuine enthusiasm for these works draws us to them in turn, suffusing them with a love that makes them come alive on the page. By transferring their emotional connections to their readers, Dillon and Marraccini enable us to newly embody these affinities, completing the cycle of criticism by creating a mutualistic bond between artist, critic, and reader. This collaborative process may represent the future of criticism, a new form of creation that transforms works of art into living, evolving things.

N.B.:

“The bagel has emerged as the unofficial food of official Washington. It’s not just a matter of importing either. D.C. itself has become a burgeoning bagel hub.” (Sam Stein with a fun report for Politico) [I remain to be impressed. I know some people feel strongly about this, but they are wrong. I earnestly wish the situation were otherwise, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves. —Chris]

A new podcast series from The Point, “Selected Essays,” is “about essays you should read but probably haven’t,” just like this newsletter.

Wired profile of Bookshop.org founder: “There’s more. This fall, Bookshop will publish a collection of short stories by Lydia Davis—a partnership about as glam as having Miuccia Prada design a capsule collection for some tiny boutique.” [Moving my workflow from Amazon links to a Bookshop.org page is one of the items on my very long list of WRB admin overhead tasks. —Chris]

More words! (Ed Simon at Lithub)

María Kodama, “a writer and translator but best known as the widow of Jorge Luis Borges,” R.I.P. See Joel J Miller’s post: “From the time of his death to hers nearly four decades later, Kodama ensured Borges’s books were edited, translated, updated, published, and protected from copyright infringement. She signed contracts, sued, and was sued. According to Halford, who interviewed Kodama in 2016, she called the period ‘thirty years of hell.’”

Al Jaffee, R.I.P.

“a few hundred people boosting a book they admire can do a whole lot to shake up a books entire trajectory” (Lincoln Michel)

Local:

Les Mis is at the Kennedy Center through the 29th.

On Saturday afternoon at the National Gallery: All That Heaven Allows (dir. Douglas Sirk, 1955) starring Jane Wyman.

Tonight at the Phillips Collection, “a hands-on workshop exploring photographic techniques.”

Upcoming book:

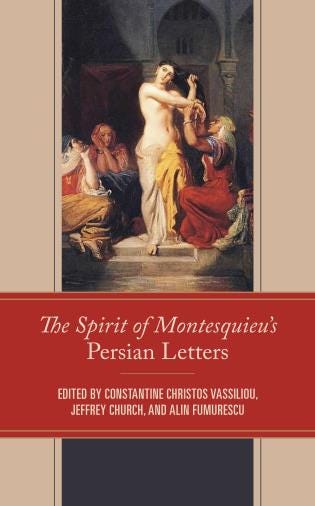

April 15 | Lexington Books

The Spirit of Montesquieu’s Persian Letters

edited by Constantine Christos Vassiliou; Jeffrey Church and Alin Fumurescu

From the publisher: This book’s primary purpose is to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Montesquieu’s Persian Letters, a seminal book in classical liberal thought. Persian Letters is a delightfully rich, sympathetic satire of commercial society’s promise and discontents, covering a wide range of issues and themes that shaped the direction of liberal modernity. It consists of a series of letters largely written by two Persian travelers to Paris, who allow modern readers to view Parisian life from the perspective of an outsider. The volume includes contributions from prominent scholars of Montesquieu’s and early career scholars who have recently unearthed new and exciting avenues for understanding this important hinge-figure in modern political thought.

What we’re reading:

A few months ago Nic remarked to Chris that Muriel Spark writes her novels from the perspective of God. Chris has been reading her short stories this week, though, and thinks she must have written them from the perspective of someone who has very ticked off and in a hurry.

Poem:

“Orchids Are Sprouting From the Floorboards” by Kaveh Akbar

Orchids are sprouting from the floorboards.

Orchids are gushing out from the faucets.

The cat mews orchids from his mouth.

His whiskers are also orchids.

The grass is sprouting orchids.

It is becoming mostly orchids.

The trees are filled with orchids.

The tire swing is twirling with orchids.

The sunlight on the wet cement is a white orchid.

The car’s tires leave a trail of orchids.

A bouquet of orchids lifts from its tailpipe.

Teenagers are texting each other pictures

of orchids on their phones, which are also orchids.

Old men in orchid penny loafers

furiously trade orchids.

Mothers fill bottles with warm orchids

to feed their infants, who are orchids themselves.

Their coos are a kind of orchid.

The clouds are all orchids.

They are raining orchids.

The walls are all orchids,

the teapot is an orchid,

the blank easel is an orchid,

and this cold is an orchid. Oh,

Lydia, we miss you terribly.

[This is from Akbar’s 2017 collection Calling a Wolf a Wolf. I have conflicted feelings about this poem, honestly. On one hand, I’m, as of late, at my breaking point when it comes to repetition as a device in contemporary poetry—it’s so often done, and often poorly. I think it’s trite. I once heard a good rule of thumb for repetition in a poem is that if the repetition changes or advances the meaning of the repeated phrase, then it’s being used well. I find that to be a decent rule. That’s not what Akbar is doing here, though, and it doesn’t entirely fail. I think the extent to which it succeeds is because there’s variations in the non-orchid images and in where the word “orchid” falls on the line. What does work for me here is that last sentence—it’s like a lightswitch gets hit and there’s suddenly light thrown onto the whole poem. That moment makes it easier to forgive the amount of times I just had to read the word orchid. —Julia]