WRB—April 8, 2023

“fire will issue forth out of my mouth and consume all the world”

Despite some concerns, the WRB is not “violent or misleading content that could lead to real-world harm.” It does not “mislead people or disrupt their experience.” [In other words, it is not a novel. —Steve]

Links:

In the LRB, Toril Moi on Marguerite Duras:

Duras’s notion of the ‘look’ shares some terrain with Sartre’s—we are talking about domination and subjection—but the differences are more striking than the similarities. For Sartre, the person looking always dominates the person being looked at. Let’s imagine that I’m peeping through a keyhole. Suddenly I hear steps in the hotel corridor. Instantly, I see myself as seen by the other, and am covered in shame. Duras inverts the power relationship: for her, the person doing the looking is revealing weakness. Any interest in another is a sign of submission. To look is to be passive, “fallen” or “degraded.” To look makes you vulnerable, because what you look at reveals your desire. The young girl in L’Amant declares that she doesn’t love the man. Yet she craves his gaze: by looking at her, he becomes her inferior; refusing to look back, she exults in her own power.

Two in Tablet:

Kenneth Sherman on Isaac Rosenberg:

In poetry, he showed no interest in adopting the techniques of the emerging imagists or of the Georgian poets who were popular during his lifetime. He was a traditionalist, working through the masters to fashion a voice. Side-stepping the dictates of modernism, he expressed his prophetic visions in an original language that synthesizes the anachronistic with the contemporary. He seems to have absorbed much of Blake, a kindred spirit in terms of social class, education (or lack thereof), and engraving skills. He would quote stanzas from Keats and Shakespeare and had an exaggerated fondness for Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the other pre-Raphaelites. When he showed up at the front in June 1916, it is reported that he’d forgotten his requisite towel but had remembered to bring a copy of John Donne’s poems, which he carried in his pocket throughout the war.

Maggie Phillips on the history of the Holy Grail:

The idea of a (Holy) Grail seems to have kicked off out of nowhere in the 13th century, spawning a variety of weird, eerie stories that involve unidentified disembodied hands extinguishing candles, mysterious chapels in the woods, and talking severed heads. They also often conclude with a lot of narrative loose ends. These mystifying stories with no readily apparent historical catalyst have created what scholars call “the Grail problem” of trying to determine just what the Grail is, and why. Wood describes a “proliferation of theories” as scholars through the years have tried to synthesize the complex nature of the various diverging Grail romances into a single coherent narrative.

In JSTOR Daily, S. N. Johnson-Roehr on a collection of Japanese woodblock prints at Boston College (available online here):

Ukiyo-e translates literally as “picture(s) of the floating world.” Ukiyo, the “floating world,” was originally “a Buddhist concept of the transitory, insubstantial nature of human existence,” explains art historian Donald Jenkins. But by the Tokugawa (Edo) period (1615–1868), the phrase evoked “the pleasures of human life, especially those associated with the brothel districts and the amusement quarters, even while some remnants of its earlier connotations remained.”

In the Boston Review, Robin D. G. Kelley on a French TV show from 1969 featuring Thelonious Monk and a documentary (Rewind and Play, 2022) about its making:

Near the end of the film, Gomis strings together several of Renaud’s monologues. Over his droning, tedious voice, Monk launches into a fierce, stride piano rendition of “Epistrophy.” The effect is cacophonous, as if they are fighting over space or shouting to be heard. In the middle of it all, Renaud recalls one night at Tony’s in Brooklyn when a melee erupted, tables were overturned, bottles sailed across the room, knives came out, and Monk and Sonny Rollins continued to play, unfazed. The way he tells it comes across as racist and voyeuristic, with “young Black people, dancing brilliantly,” amid “a fight like you see in the best American movies.” I know it happened because the late Randy Weston was also there, and he has told me the story many times. But something about Renaud’s tone doesn’t sit right.

Reviews:

In the New Yorker, Katy Waldman reviews a new novel by Esther Yi (Y/N: A Novel, March):

If this doesn’t sound like typical fan fiction, that’s because the narrator doesn’t see herself as a typical fan. (She’d probably identify as a hater.) Bubbly enthusiasm is not in her nature. “My spiritual sphincter stayed clenched to keep out the cheap and stupid,” she declares. And solidarity offends her; she loves only “that which made me secretive, combative, severe.” What seduces her is not Moon, exactly, but the prospect of using him to transcend everyone else, excising “them from my perception of space.” At Moon’s concert, she imagines vaulting onstage to intercept her prize, floating above the crowd, her own outlines brightening. “For a single moment in time,” she thinks, “I would be all that he saw.”

In The Nation, Will Self reviews a new translation of a novel by Mircea Cărtărescu (Solenoid, trans. Sean Cotter, 2022):

Whatever the vagaries of translation from one language to another, there remains the Nietzschean problem of the incommensurability of language and experience, for us and for Cărtărescu’s alter ego. For while he madly maintains the fragments of his bodily existence—his umbilical twine, his baby teeth, the plaits his mother tied his hair in when she was raising him as a girl—so he writes obsessively, but not for publication. In this, he exactly parallels his creator—for just as the counter-Cărtărescu is split from the real one by the negative reception of his epic poem (whereas the real Cărtărescu was lauded for The Fall), so the obsessive journals he keeps mirror the real ones his creator has kept throughout his adult writing life. At the end of Solenoid, these alternative journals are burned by the narrator—becoming as one with the counter-life they have described. The only conclusion possible is that they are the real lived substratum to the novel that Cărtărescu’s readers hold in their hands.

“Linguistic slush like this will not trouble unbelievers. But for Christians, it is important that someone claiming to articulate a Christian perspective on art and language take more care over his own verbiage.” (Emeline McClellan for University Bookman) [I think linguistic slush should trouble everyone. —Chris]

In Literary Review, Tess Little reviews Annie Ernaux’ diary of visiting the supermarket (Look at the Lights, My Love, trans. Alison L. Strayer, April):

Across thirty-five entries, Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux provides “a free statement of observations and sensations, aimed at capturing something of the life of the place”—including its various rules. Customers cannot carry backpacks, must wrap purchases from elsewhere in plastic and should refrain from taking photographs (Ernaux, failing on the last two counts, is duly reprimanded). Then there are the norms of “consumer civility.” We keep our distance; we bristle when someone ahead is slow to pay; we turn a blind eye when one or two grapes are popped in the mouth pre-purchase.

Lithub has up a new translation of a 2004 conversation between Ernaux and Yuko Tsushima: “I think both men and women write this way and there’s really no fundamental difference. I mean, there are male writers who basically publish their diaries.”

In the Sydney Review of Books, Patrick Allington reviews a collection of essays by Elaine Castillo (How To Read Now: Essays, 2022):

In turn, though, I agree with Castillo’s critique of empathy, despite having drunk more than my fair share of what she calls ‘ethical protein shakes’. I find her viewpoint, and those of Serpell and Tumarkin, compelling. The act of reading does not guarantee prompt action, or any action, or the right action. It does not guarantee a particular outcome—or even the first step towards one. It does not turn readers into good people, any more than writing a book means you must be an ethical person. Empathy does not create a reader who is necessarily empathetic in the right ways, let alone guaranteeing influence over others or, especially, changing systems and power.

N.B.:

Registration for the Catherine Project’s Summer offerings is now open.

The new issue of Image, number 116, is now available.

For instance, see Elizabeth Harper on some of the stranger Madonnas of Italy.

Related, Marta Figlerowicz shares some off-cuts about a strange saint from her Art of Fiction interview with Olga Tokarczuk in the Spring issue of The Paris Review.

The Spring issue of Humanities is available as well.

See for instance Alyson Foster’s feature on Martha Gellhorn, who had more going on than being Hemingway’s third wife.

Guernica now has issues, starting with April’s.

“Picasso’s pictorial pyrotechnics can be astounding. But the emotional core—or an emotional core that we might care about—often seems absent. Gopnik’s essay was hugely controversial at the time. But a quarter century on, it looks courageously clearheaded, and in many ways, the world has come around to the heretical position he advanced.” (Sebastian Smee in the local Post)

Fun from LRB:

Local:

There are plenty of tickets left for the last three shows of the Joffrey Ballet’s Anna Karenina at the Kennedy Center, through tomorrow afternoon.

The Washington Stage Guild is playing Ben Butler through the 16th.

Upcoming book:

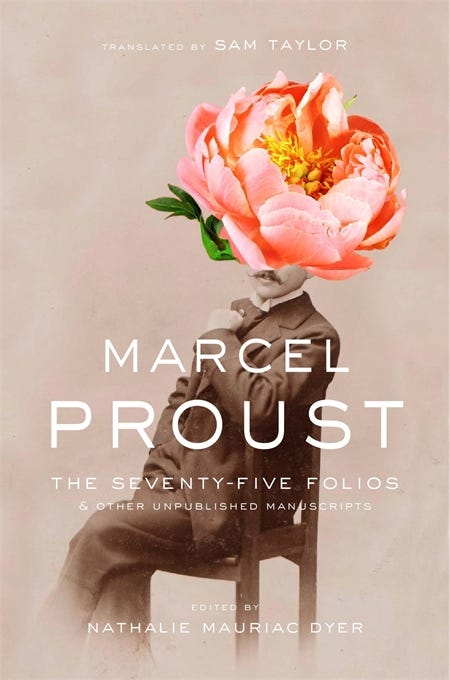

April 25 | Harvard University Press

The Seventy-Five Folios and Other Unpublished Manuscripts

by Marcel Proust, edited by Nathalie Mauriac Dyer, translated by Sam Taylor

From the publisher: One of the most significant literary events of the century, the discovery of manuscript pages containing early drafts of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time put an end to a decades-long search for the Proustian grail. The Paris publisher Bernard de Fallois claimed to have viewed the folios, but doubts about their existence emerged when none appeared in the Proust manuscripts bequeathed to the Bibliothèque Nationale in 1962. The texts had in fact been hidden among Fallois’s private papers, where they were found upon his death in 2018. The Seventy-Five Folios and Other Unpublished Manuscripts presents these folios here for the first time in English, along with seventeen other brief unpublished texts. Extensive commentary and notes by the Proust scholar Nathalie Mauriac Dyer offer insightful critical analysis.

Characterized by Fallois as the “precious guide” to understanding Proust’s masterpiece, the folios contain early versions of six episodes included in the novel. Readers glimpse what Proust’s biographer Jean-Yves Tadié describes as the “sacred moment” when the great work burst forth for the first time. The folios reveal the autobiographical extent of Proust’s writing, with traces of his family life scattered throughout. Before the existence of Charles Swann, for example, we find a narrator named Marcel, a testament to what one scholar has called “the gradual transformation of lived experience into (auto)fiction in Proust’s elaboration of the novel.”

Like a painter’s sketches and a composer’s holographs, Proust’s folios tell a story of artistic evolution. A “dream of a book, a book of a dream,” Fallois called them. Here is a literary magnum opus finding its final form.

Written up by Claire Messud in the last issue of Harper’s: “Even in these early sketches, his prose dazzles and thrills, by turns depicting recognition and wonder, sometimes overdone but always with the precise intelligence, meditation, and humor for which Proust is renowned.”