WRB—Aug. 16, 2025

“slender works of female collapse”

[My apologies if you are receiving this twice; something went wrong with my first attempt to send it out. —Steve]

For these local families of distinction were convinced that not only one’s family but one's wealth was the be-all and end-all of every happy union meant to include social security. And in consequence, while considering Clyde as one who was unquestionably eligible socially, still, because it had been whispered about that he was a managing editor, they were not inclined to look upon him as one who might aspire to marriage with any of their daughters.

Links:

Reviews:

Two in the TLS:

Paul Griffiths reviews a book about Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time (Quartet for the End of Time: Music, Grief, and Birdsong, by Michael Symmons Roberts, April in the UK):

This movement enthralls Symmons Roberts to the extent that he once, from what he confesses to be a position of almost total musical ignorance, contemplated taking up the clarinet to play it. (The Quartet is written for clarinet, violin, cello and piano, the instruments available in the camp.) Better what he makes of it here in his true métier. The word “abyss”, he discovers in his Compact OED, has its antonym in “byss,” meaning bottom or ground, the “abyss” having no such limit. As for the birds, they sing in some of the book’s most beautiful pages. Sitting in a café garden in Berlin, Symmons Roberts hears the song of a “blackbird-mezzo . . . heavier than the air, that floated down and filled the space around me.” He pays homage to the birdsong recordings of Ludwig Koch and goes to the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris to study the notebooks Messiaen filled with transcriptions. He also has an “Abyss of Birds” of his own, a fifteen-line, single-sentence poem in which the songs of all the birds that have ever been plunge spiralling down “in one tremendous rinse and swoon of multiples” into a single note in the throat of a thrush.

[We linked to a review of two other books about Messiaen in WRB—Feb. 15, 2025.

“A single note in the throat of a thrush”? Yes, but we hear from Robert Browning:

That’s the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

And repetition, that initial moment duplicated, can through its own repetition become infinite. Messiaen writes in his notes to the “Praise to the Eternity of Jesus”:

Jesus is considered here as the Word. A broad phrase, “infinitely slow,” on the cello, magnifies with love and reverence the eternity of the Word, powerful and gentle, “whose time never runs out.” The melody stretches majestically into a kind of gentle, regal distance. “In the beginning was the Word, and Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

Repeat the note, repeat the moment, and time never runs out. —Steve]

Mary C. Flannery reviews a book about the Pearl manuscript (Chasing the Pearl-Manuscript: Speculation, Shapes, Delight, by Arthur Bahr, March):

Though the four poems are quite different from one another, they all exhibit what one scholar has described as “a passion for pattern.” Take the concatenated clusters of stanzas in Pearl, in which a word or phrase from the final line of one stanza appears in the first line of the next. These lead eventually to the final line of the poem, which echoes its first, bringing the reader full circle and evoking formally the perfect sphere of the titular gem. Numerological features and references abound throughout the manuscript, from the obsession with the number three in Cleanness to the 101 stanzas that make up both Pearl and Sir Gawain, a total that Arthur Bahr describes as “a suggestively not-quite-perfect number that evokes the slight-but-real climactic misstep of their respective protagonists.” As his study makes clear, Bahr finds both the manuscript and its poems to be “generatively imperfect,” embodying an “aesthetics of inexactness.” This inexactness, he argues, is meant to draw the reader onward through the sequence of poems and inward via contemplation.

In RealClearBooks, Kazuo Robinson reviews Graham Watson’s biography of Charlotte Brontë (The Invention of Charlotte Brontë: A New Life, August 5) [The Upcoming book in WRB—July 30, 2025.]:

One is pleased and a little relieved to read a literary biography with a sensibility that enlivens and remembers why its subject is worthy of discussion. Watson has to reckon with the standard achieved by Gaskell in the Life, which begins with a remarkably immersive narrated journey from the train station at Keighley, up to Haworth, and into the church where many of the Brontës are buried. His New Life has some heavy weather, which gives the Brontëan landscape its majesty. After Gaskell’s visit to the parsonage where she hoped to collect some materials, she is delayed on her way back to Manchester: “The pressure of the sultry evening brought a darkness troubled by rolling peals of thunder. Torrential rain flooded the reservoir high up on the moors, bursting the banks of the stream that ran through Thornton, the place of Charlotte’s birth, sweeping away everything in its path.” And Watson also permits himself here and there the droll humor of the Scotsman. This consists first in understatement. Brontë’s father, Patrick the vicar, and her widow, his curate Arthur Bell Nicholls, hoped to be hymned and praised along with her in Gaskell’s Life: “All that stood in their way were the contents of Charlotte’s letters and everything she had told her about both men.” And second, in the careful timing of bathos. Charlotte’s friend from boarding school, Ellen Nussey, whose letters are used all over the Life to provide the account of Charlotte’s emotional travails, learned of a £100 goodwill payment to Arthur. “Ellen—an unmarried, unemployed woman living on savings and dividends from private annuities—wondered if her own contribution merited some compensation too. She received it eventually: a free copy of the book.”

[I had a lot to say about Charlotte’s relationship with her family in WRB—March 2023 Film Supplement. —Steve]

Two in Literary Matters:

Tim Tibbitts reviews a book about James Wright and translating poetry (So Much Secret Labor: James Wright and Translation, by Anne Wright, Saundra Rose Maley, and Jeffrey Katz, March):

Beyond the impact translation had on his work, the authors make the case that the practice was central to his development as a person. Katz suggests that “[h]is work with translations would give Wright greater access to his own tenderness, anger, melancholy, and reverence by way of such a personal rhythm, without the constraint of what he called ‘rhetoric.’ In other words, he found in the Spanish and Latin American poets, in particular, a tonal directness, a language highly sophisticated, but left ‘unmanaged’ by the intellect and its New Critical partners—irony, tension, and paradox.” Wright himself makes the point even more emphatically in a letter excerpted in the “Nourishment” section, in which he says of the Peruvian poet César Vallejo, “I owe him so much because he reminded me that perhaps I too, might somehow vindicate myself not only as an artist, but even, as a human being.”

[I always feel compelled to note that freeing oneself from irony, tension, and paradox is trading one rhetorical strategy for another. —Steve]

Erick Verran reviews a collection by Christian Gullette (Coachella Elegy, 2024):

It is clear that Gullette’s style, chiseled by grief, has mostly outswam the tide of literary faddism. The advantage of saying less is that one doesn’t, of course—except he could do without the DJs and Jell-O shots, which read like a pop refrain. Then, compared with the diminutive charm of “Bees in the Maraschino Cherry Factory” or “Seahorse with Cotton Swab,” Gullette’s titles occasionally disserve the poems they open for, amplifying their minimalism. If phrasing less at-hand than “Clothing Optional” and “Election Night” wouldn’t necessarily have wrinkled his starch-crisp voicing, Gullette’s endings have the effect of slightly qualifying matters, of leaving the air charged with ambiguity: the detail one neither immediately notices nor entirely misses, such as “the clink / of forks as people laugh // and touch each other on the shoulder / when they agree.” These soft about-faces, a neutral mystery equal parts studium and punctum, simultaneously disarm and elevate; there is a note of severity you didn’t hear earlier in the poem, and now it’s over. The sharpest of these include being told that the reform school, from where Gullette’s brother has mailed him a letter for batteries, doesn’t allow its boarders to keep electronics.

[Elide the title—“Cochell’ Elegy”—and it’s fun to say, a movement from the back of the mouth to the front. —Steve]

In the local Post, BDM reviews a translation of a novel by Marlen Haushofer (Killing Stella, 1958, translated from the German by Shaun Whiteside, July 8) [An Upcoming book in WRB—July 5, 2025; we linked to an earlier review in WRB—June 28, 2025.]:

Clocking in as it does at fewer than 100 pages, Killing Stella will make even the firmest devotees of the “slender works of female collapse” genre—among whom I number myself—wonder if the book is really worth their money, time and attention. The answer is yes. Killing Stella is an accomplished work of real-life horror, the documentation of a woman whose choices have entombed her alive in a comfortable hell. Anna vacillates between seeing herself in purely passive terms and seeing herself as someone who could have acted but did not. But most impressive is how the reader is made to see the things that Anna does not allow herself to know about herself.

For instance: Given her thorough understanding of her husband’s nature, why agree to bring a teenage girl to live with them? When Stella arrives and is too drably dressed to attract Richard’s attention, why make a point of transforming her into a beauty? Passive and helpless as she perceives herself to be, Anna nonetheless serves Stella up to her husband as a present, gift-wrapped in a pretty dress. She orchestrates the beginning of the affair, even as she condemns herself for standing helplessly by. Anna, undoubtedly a victim of her possessive but unloving husband, is also his accomplice, and deciphering her deeper motivations causes this apparently lightweight book to become suddenly vast in its scope and implications.

In The New Republic, Mychal Denzel Smith reviews a collection of Jamaica Kincaid’s essays (Putting Myself Together: Writing 1974–, August 5):

Having been introduced to Jamaica Kincaid as a fiery postcolonial critic and knowing her later career as a chronicler of her beloved garden, the essays that comprise the first part of this collection feel as though they were written by someone else. There’s a knowing, hipper-than-thou affect evident in the articles on Muhammad Ali, Patti Labelle, and Diana Ross, and she showed her humor early (describing the crowd gathered to watch the Ali fight at the Victoria Theater in a Village Voice essay: “No one looked as if they had gotten dressed up for the event. The closest thing to being glamorous anyone came was one man who walked around with an orange-colored Panasonic cassette player”), but is also mean in that way a twentysomething can be. (On Diana Ross: “Black people always say that they have one face for white people and when they are by themselves they are real. I have never for a moment thought that there was a Diana Ross more real than the one I could see.”) These are not essays of grand searching, but they don’t appear to have been reaching for much of anything at all—not that I would want anyone digging up writing from my early adulthood, for which the same could be said. Their inclusion in Putting Myself Together lends itself to a query: Does Jamaica Kincaid still like these essays, or are we to read them as folly? Did she want us to see them as great writing (they are fine for what they are) or as part of the collection’s own narrative structure—struggling toward greatness?

[If the lines quoted here are mean they are also neatly observed. And isn’t that enough for an essay? Seek truth from facts, seek truth from neat observations. —Steve]

In the Journal, Donna Sanders reviews James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans (1825):

Drawing together characters of different cultures, ethnicities and faiths, Cooper paints a vibrant panorama of life on the eighteenth-century frontier, where identities merge and mingle. The many-sided nature of the American self is best epitomized by Natty, a child of European parents who grew up among indigenous tribes and Moravian missionaries, and who refers to himself as a “man without a cross.” The warm, honest scout reveres untamed nature and regrets the encroachments of modern society. His independent spirit speaks to young America’s desire to fashion itself as a proud beacon of rugged individualism.

Self-fashioning, disguise and deceit power Mohicans, leading to some of the novel’s most memorable moments. Maj. Duncan Heyward, the impassioned fiancé of Alice Munro, dons the costume of a French juggler to rescue his love from the secluded cavern where enemies hold her captive. Lt. Col. Munro dresses up as a “plain woodsman” as he searches for his missing daughters. Magua moves stealthily among friends and foes alike while executing his plot for revenge on the European colonizers. Amid this great gallimaufry of shifting identities and alliances, Cooper crystallizes an image of America as a “scene of strife and bloodshed” where the battle for virtue rages ever on.

[I think in the next few years we’re going to see more interest in the original nineteenth-century attempts to create a specifically American literature, both because going back to the sources is a good way to deal with getting stuck and because claiming to represent true American literature is an attractive thing for a literary movement. —Steve]

N.B.:

“The Mystery of the Soft Balls Rocking Cricket” [It’s good to know that our English cousins are just like us. —Steve]

“How Do You Spot a ‘Performative’ Male? Look for a Tote Bag.” [You can buy a WRB tote bag, if you feel so inclined, here. (I’ll know I’ve made it when people start carrying them around performatively; help me make my dreams come true.) I, on the other hand, am the sort of person who was recently sent an Onion article titled “Man Wishes Women In Crowded Bar Would Let Him Read Jane Austen Novel In Peace.” —Steve]

New issue: Literary Matters 18.1 (Fall 2025)

Poem:

“Metaphor” by Claudia Emerson

We didn’t know what woke us—just

cold moving, lighter than our breathing.The world bound by an icy ligature,

our house was to the bat a warmerhollowness that now it could not

leave. I screamed for you to do somethingSo you killed it with the broom,

cursing, sweeping the air. I wantedyou to do it—until you did.

[There have been mice in my shared house for at least the last two years and in that time, I’ve trapped and rehomed several generations of mouse families. I won’t set out glue or snap traps because I can’t bear to think of them struggling for hours and failing to die. But I must have left a have-a-heart trap set, though not baited, during the time when we were all traveling, because the mice are quite loud in the traps and I don’t remember hearing anything. Only last week I discovered the trap had sprung, a mouse dead inside. Its little body was desiccated, coiled in on itself. I laid it beneath a tree in our yard and covered it with fallen flowers. Which to say, I am familiar with Emerson’s regret, the bitter fruits of fear or carelessness. The poem moved me with its stark and quiet savagery: “[t]he world bound by an icy ligature/our house was to the bat a warmer / hollowness that now it could not / leave.” —K. T.]

Upcoming books:

Yale University Press | August 19

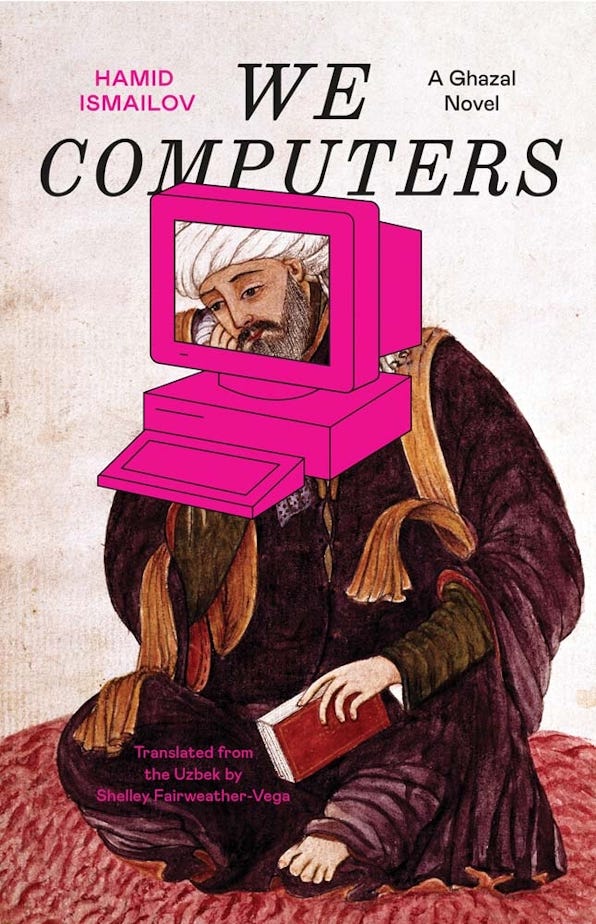

We Computers: A Ghazal Novel

by Hamid Ismailov, translated from the Uzbek by Shelley Fairweather-Vega

From the publisher: In the late 1980s, French poet and psychologist Jon‑Perse finds himself in possession of one of the most promising inventions of the century: a computer. Enchanted by snippets of Persian poetry he learns from his Uzbek translation partner, Abdulhamid Ismail, Jon-Perse builds a computer program capable of both analyzing and generating literature. But beyond the text on his screen there are entire worlds—of history, philosophy, and maybe even of love—in the stories and people he and AI conjure.

Hamid Ismailov brings together his work as a poet, translator, and student of literature of both East and West to craft a postmodern ode to poetry across centuries and continents. Crossing the poètes maudits with beloved Sufi classics, blending absurdist dreams with the life of the famed Persian poet Hafez, moving from careful mathematical calculations to lyrical narratives, Ismailov invents an ingenious transnational poetics of love and longing for the digital age. Situated at the crossroads of a multilingual world and mediated by the unreliable sensibilities of digital intelligence, this book is a dazzling celebration of how poetry resonates across time and space.

Also out Tuesday:

Amistad: Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler by Susana M. Morris

Dalkey Archive Press: The Sugar Kremlin by Vladimir Sorokin, translated from the Russian by Max Lawton

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: Baldwin: A Love Story by Nicholas Boggs

Tin House: Archipelago: A Novel by Natalie Bakopoulos

What we’re reading:

Steve finished An American Tragedy (by Theodore Dreiser, 1925). [It is hard, now, not to perceive An American Tragedy as a fusion of Thomas Hardy and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and in both cases the comparison is not to Dreiser’s advantage. In writing an unrelentingly bleak novel in which terrible things happen over and over to a protagonist with whom the novelist obviously sympathizes, Dreiser is calling back to Jude the Obscure and Tess of the d’Urbervilles. And yet Clyde Griffiths has more agency than Hardy’s heroes and creates many of his own problems in a way Jude, let alone Tess, does not. His tragedy is not that the society he is born into must necessarily crush him; his tragedy is that, as the defense keeps insisting at his murder trial, he is a “mental and moral coward.” (The logic there is that therefore he is hardly capable of murder.) He created a situation, merely by drifting along, where he considers killing a poor woman he has impregnated so she will not spoil his potential marriage to a rich woman. The fault is not in his stars but in himself—how sympathetic can he really be?

And his fault is his ambition, an ambition which takes the form of wanting to marry a rich girl. This material reads like The Great Gatsby, which came out the same year as An American Tragedy, if Fitzgerald modeled his prose not on Keats but on quicksand. Like Daisy Buchanan, Sondra Finchley is not merely a woman but a representative of an entire way of life—endless leisure, endless ease, floating above the harsh and brutal world the poor boy has known his whole life. Unlike Daisy Buchanan, Sondra Finchley is insipid. She spends much of the novel talking in scarcely believable baby talk, for example: “Whatever matter wissum sweet to-day? Cantum be happy out here wis Sondra and all these nicey good-baddies?” This is too goofy to be taken seriously. Whenever Dreiser gets away from the main events of his plot he sees America as a place where some are born to sweet delight, some are born to endless night, and the former will never understand the latter. Their money has made them invulnerable. They can ignore whatever they do not wish to see. But the story that brings it all together is—this? What does Clyde Griffiths reveal about anything besides Clyde Griffiths?

The tragedy of Clyde Griffiths, which he does not see, is that whenever he gets close to wealth he acts as if he has the impunity it brings without actually having it. For this he is sent to the electric chair. The tragedy of Roberta Alden is that she has been seduced and abandoned, and her attempts to secure some provision from the man who seduced and abandoned her cause her death. These are not quite the same thing. The first is American; the second is tragedy. —Steve]

Critical notes:

Kids can be fickle, lazy and easily bored. So can adults. Parents will buy a pet for their children as a way to teach them responsibility and sometimes the theory works. In the sixties we had a Siamese cat named Ming Tai, a beautiful creature. We attached her leash to the clothesline in the back yard so she could enjoy the outdoors without escaping. We were told never to leave her unsupervised. One day my brother wandered off, the cat climbed the apple tree and hanged herself. A little later, my maternal grandmother gave me a caiman, a scaled-down alligator, mostly to irritate my parents, I suspect. I kept her in a shallow glass container, a sort of a casserole dish, and fed her raw ground beef. One summer day I left her on the picnic table in the backyard. When I returned, she was gone, probably to the creek that flowed at the bottom of the hill behind our house.