WRB—Aug. 2, 2025

“answer your own questions”

“How long are they gonna worship this guy?”

“Hey! We got Managing Editors over here!”

Links:

Two in the TLS:

Daniel Karlin on a year without reading anything:

If I were asked, for example, where these lines came from—“As new wak’t from soundest sleep / Soft on the flourie herb I found me laid / In Balmie Sweat, which with his Beames the Sun / Soon dri’d, and on the reaking moisture fed”—I would have no difficulty in identifying them as the beginning of Adam’s account, in book 8, of what he remembers of his own creation; but if asked “How does Adam begin his account of what he remembers of his own creation?”, I would be unable to reproduce these words. The same holds true for Shakespeare; as an experiment, I attempted a “memorial reconstruction” of Hamlet, like the actors supposedly responsible for the Bad Quarto of 1603; this is a play I know inside out, but my version of it, which I recorded over several days, made the Bad Quarto look Good, to say the least. At the same time, my head is filled with quotations, which surge into consciousness when I need them (and sometimes whether I need them or not); there is a difference, obviously, between the voluntary effort to remember a book and the latent, enduring “presence” of that book in one’s memory, but it was still disconcerting to find that, if I had been asked to participate in the famous last scene of François Truffaut’s film adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 (1966), I would have been unable to introduce myself by saying “I am the poems of Robert Browning,” or even “I am a few poems by Robert Browning,” but only “I am a few scattered verses by Robert Browning, some of which may not even be by him.” On a desert island, I would be without resource.

[I feel like Karlin’s one exception to not reading anything, which was “to continue the textual collation of manuscripts of a number of poems by Robert Browning” because he was under contract to do so and didn’t want to delay his co-editors, makes the whole project rather like deciding not to drink if your job occasionally required you to drink whiskey straight from the bottle.

It is funny how much of my knowledge of things in books is “the passage about this is on a page on the left, about halfway down, two-thirds of the way through the book,” which is not really knowledge about the content of a book but instead knowledge of the physical item. For the WRB I look things up in my books a fair bit—if there’s not an index, this sort of knowledge ends up being pretty useful. In related news I now find books without indexes much more infuriating. —Steve]

Tim Parks on teaching English in Italian classrooms:

If the task is teaching literature, why muddy the waters? Watching a film is quite different from reading a book, and there’s the danger of suggesting that literature can be reduced to a content that might just as well be expressed in a different medium; all we need to know is that Jane marries Rochester, Pip inherits a fortune, Tess meets a gruesome end. But this is not the case: literature requires and nurtures a competence with language, exploring our ancient habit of constructing worlds with words. Film is a different enchantment.

But the business of hope? “My students get so discouraged,” one teacher tells me. And I’m stumped. I honestly can’t think of any books important to me that seem designed to instill confidence in the future of humanity. And I wonder why I never felt this need for hopeful literature. Nor can I imagine my teachers, back in the 1960s and 1970s, fretting about this. We were in class to read the best that had been written by forebears and contemporaries, to see how different visions and modes of expression had built up a mental landscape that had to do with us now, a landscape that included murderous Macbeth, the madness of Miss Havisham, the crushing of Winston Smith. It was taken for granted that life was perilous.

[People are showing their students the Polanski Tess (1979) in class? It’s one of the best movies I’ve seen, but I have to wonder who out there thinks their students can’t handle a book on its own and believes the solution to this problem is a three-hour movie full of shots that look like landscape paintings.

For the record, the movies I recall watching in high school were the Zeffirelli Romeo and Juliet (1968) (a waste of time), the Baz Luhrmann version of the same (1996) (great until Mercutio dies and Luhrmann doesn’t realize that the tone has changed), and the Zeffirelli Hamlet with Mel Gibson (1991) (a waste of time). These genuflections to the idolatrous screen were permitted, I assume, because my teachers thought we would benefit from hearing Shakespeare spoken. The idea that we should have watched any other movies would have been met with incredulity, but not as much incredulity as the idea that they were supposed to inspire hope in their students, or do anything else aside from teach English. You can’t—I can hear them saying this with unconcealed exasperation—apply Macbeth, say, to your life, or get anything useful out of it, unless you first understand it. To not understand this is to not understand what books are, or how reading works.

If, reading this newsletter, you have ever thought that the Managing Editor is the crankiest, most crotchety, and oldest 26-year-old alive, know that I was educated by people even crankier and more crotchety than I am, who have had far more time to practice the art of yelling at clouds. (A couple of you, I think, are reading this. Hi! I love you.) —Steve

In The New Statesman, Frances Wilson on Hans Christian Andersen:

Andersen, a dreamy and effeminate only child, preferred his own company. His favorite pastime was the toy theater made by his father, for which he wrote plays to be performed by the dolls whose clothes he designed and sewed. His first production was a tragedy taken from a song in Pyramus and Thisbe, the play within the play performed by the mechanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “Everyone was obliged to hear my play,” Anderson recalled in his first memoir, The True Story of My Life, written when he was 27 and not yet a household name. “It was a perfect treat for me to read it, and it never occurred to me that my audience might not experience the same pleasure in listening.” Anderson’s performances were mocked by the street boys who chased him home, where he wept. He also had a fine soprano voice, and was known, he recalls, as “The Funen Nightingale.” In his fairy tale The Nightingale, the bird’s voice becomes famous and moves emperors to tears, until he is replaced by an automaton.

[Are there more threatening words than “his first memoir . . . written when he was 27”? Perhaps “a song in Pyramus and Thisbe, the play within the play performed by the mechanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” —Steve]

In our sister publication on the Hudson, Ingrid D. Rowland on Veronese:

Veronese may have been, like Raphael and Rubens, a painter of impeccable manners and an expert pleaser of patrons, but along with those manners came striking sensitivity, wit, and a wicked sense of humor. Nor has every twentieth-century artist passed him over. The redoubtable painter Alex Katz (still active at ninety-eight) acknowledges that Veronese, in many ways, is his true mentor. The paintings, he maintains, project their energy vigorously outward, dominating the space in front of them—our space—rather than pulling in the viewer, a bit of magical stagecraft performed with a confidence no other painter can match: “There is no strain, it just keeps moving toward you. I still think of him as having the largest controlled gesture. The paintings are impersonal, elegant, and powerful.”

Reviews:

In the Journal, Tim Page reviews a new book about Mahler (Gustav Mahler, by Stephen Downes, June):

There have been more than 100 books about Mahler, ranging from The Mahler Album (1995), a handsome collection of every photograph of the composer known to exist, to the encyclopedic multivolume biography by the musicologist Henry-Louis de La Grange (3,600 pages in the original French, published from 1979 to 1984, then trimmed a bit for translation). We now have another, in the form of Stephen Downes’ Gustav Mahler. Do we need it?

The answer is yes, and for a few reasons. Books about Mahler tend to beget more books about Mahler—those who revere this composer feel a calling to write about him, each of them carrying, to use Walt Whitman’s words, their “special flag or ship-signal.” None of the composers who were Mahler’s rough contemporaries and in some cases his equals—Richard Strauss, Jean Sibelius, Leoš Janáček—have inspired anywhere near so much literature. Moreover, although neither of the two films that have been based on his life are at all reliable—Ken Russell’s abysmal Mahler (1974) is sensationalistic throughout, and Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971), although suffused with the “Adagietto” from Symphony No. 5, transformed the hero of Thomas Mann’s novella from an elderly author to a middle-aged composer—they have helped keep Mahler a fresh topic of conversations.

[Writing a book about someone requires a sense, if not necessarily of love and admiration, that the subject is one of “your guys,” and Mahler’s life is much more effective at creating that sense than the other composers Page mentions. —Steve]

N.B.:

The world of forensic ornithology.

“The Latest Weapons Against Wolves: AC/DC and Scarlett Johansson”

Pete Wells on the Maine lobster roll. [The manager of one lobster shack reports that in recent years tourists have moved away from getting whole steamed lobsters in favor of lobster rolls. You hate to see it. The disassembly is part of the fun. —Steve]

Air Mail has an item about the apéro dînatoire. [Are we doomed to forever be a provincial nation, impressed by French phrases of dubious merit? —Steve]

[In Wednesday’s commentary on Wyatt’s “Whoso list to hunt” I intended to mention Richard Lovelace’s “La Bella Bona Roba,” which is full of some wonderfully gross stuff about hunting, but I forgot. So instead here are some notes Victoria Moul made about it last year: “Isn’t this a fantastically horrible poem?” (That’s what you want to hear.) —Steve]

Poem:

“Scarborough Fair,” author unknown, as published by Frank Kidson in Traditional Tunes (1891)

“O, where are you going?” “To Scarborough fair,”

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme;

Remember me to a lass who lives there,

For once she was a true love of mine.And tell her to make me a cambric shirt,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Without any seam or needlework,

And then she shall be a true love of mine.And tell her to wash it in yonder dry well,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Where no water sprung, nor a drop of rain fell,

And then she shall be a true love of mine.Tell her to dry it on yonder thorn,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Which never bore blossom since Adam was born,

And then she shall be a true love of thine.O, will you find me an acre of land,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

Between the sea foam, the sea sand,

Or never be a true lover of mine.O, will you plough it with a ram’s horn,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

And sow it all over with one peppercorn,

Or never be a true lover of mine.O, will you reap it with a sickle of leather,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

And tie it all up with a peacock’s feather,

Or never be a true lover of mine.And when you have done and finished your work,

Savoury sage, rosemary, and thyme,

You may come to me for your cambric shirt,

And then you shall be a true lover of mine.

[We just finished up county fair week here in my home town. The heat wave cancelled the Draft Horse pull, which is a great sadness for us, but we still got to see the Western horse fitting & showing and pleasure riding classes. A teenage competitor saw my 3 wide-eyed girls and brought her gentle giant over for treats and pets. You've probably heard a version of “Scarborough Fair” sung by Simon & Garfunkel, though they are far from the only performers to record it.

This version was collected in Whitby by Frank Kidson, who tells us that English and Scandinavian versions of a ballad called “The Elfin Knight” are the basis for this version, printed in 1891. Kidson tells us that versions were commonly localized, with “Scarborough” regularly substituted out for the town where it was being sung.

He remembers it sung in old London neighborhoods. The story, though, is much older. Love, crossed by magic, is faced with impossible tasks to be united or reunited. —Grace]

[One thing I like about this version is the switch from addressing “her” to addressing “you.” Since it happens exactly halfway through, and since it represents a change in perspective from the original speaker to “a lass who lives there,” part of me suspects that Kidson wanted to combine two different variants with an artistic touch. (In most folk songs like this I know the two speakers would simply alternate stanzas; the framing device here makes that impossible, though. They are not in the same place and so can’t have a back-and-forth.) But I think it’s more likely that, in the way folk songs sometimes do, it preserves existing verses without really preserving who was speaking them, or to whom. The most obvious version of this is in “St. James Infirmary,” whose bizarre and haunting shifts—the singer sees his dying love in the first stanza, boasts that “she will search this wide world over / but she’ll never find another sweet man like me” in the second, and plans his own funeral in the third—are the result of a failure to preserve which character was saying what, on top of confusion introduced by the singer and the dying person being either male or female, depending on the version. (If you know “The Streets of Laredo” you are familiar with a song that shares the same ancestors in which who says what never got mixed up.) Here, it indicates a strategic intensification or a forgetting of the framing device; is the lass supposed to be speaking to the original speaker, or to the person who went to Scarborough Fair?

As Grace says, this kind of story is very old. The first ballad in Francis James Child’s The English and Scottish Popular Ballads is “Riddles Wisely Expounded,” about which he says:

Riddles, as is well known, play an important part in popular story, and that from very remote times. No one needs to be reminded of Samson, Oedipus, Apollonius of Tyre. Riddle-tales, which, if not so old as the oldest of these, may be carried in all likelihood some centuries beyond our era, still live in Asiatic and European tradition, and have their representatives in popular ballads. The largest class of these tales is that in which one party has to guess another’s riddles, or two rivals compete in giving or guessing, under penalty in either instance of forfeiting life or some other heavy wager; an example of which is the English ballad, modern in form, of “King John and the Abbot of Canterbury.” In a second class, a suitor can win a lady’s hand only by guessing riddles, as in our “Captain Wedderburn’s Courtship” and “Proud Lady Margaret.” There is sometimes a penalty of loss of life for the unsuccessful, but not in these ballads. Thirdly, there is the tale (perhaps an offshoot of an early form of the first) of The Clever Lass, who wins a husband, and sometimes a crown, by guessing riddles, solving difficult but practicable problems, or matching and evading impossibilities; and of this class versions A and B of the present ballad and A–H of the following [“The Elfin Ballad”] are specimens.

(Since Child mentions it, I want to say that Ian & Sylvia’s version of “Captain Woodstock’s Courtship” is one of my favorite recordings of any folk song.) As if to prove how common these are, Child then discusses similar songs in German, Russian, and Gaelic. And this sort of thing fits the folk song well; if you have more riddles, or more impossible tasks, as is the case here, you can always turn them into more stanzas. Inside the frame story there is only a list of riddles, after all, and that can be as long as an audience will tolerate. —Steve]

Upcoming books:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux | August 5

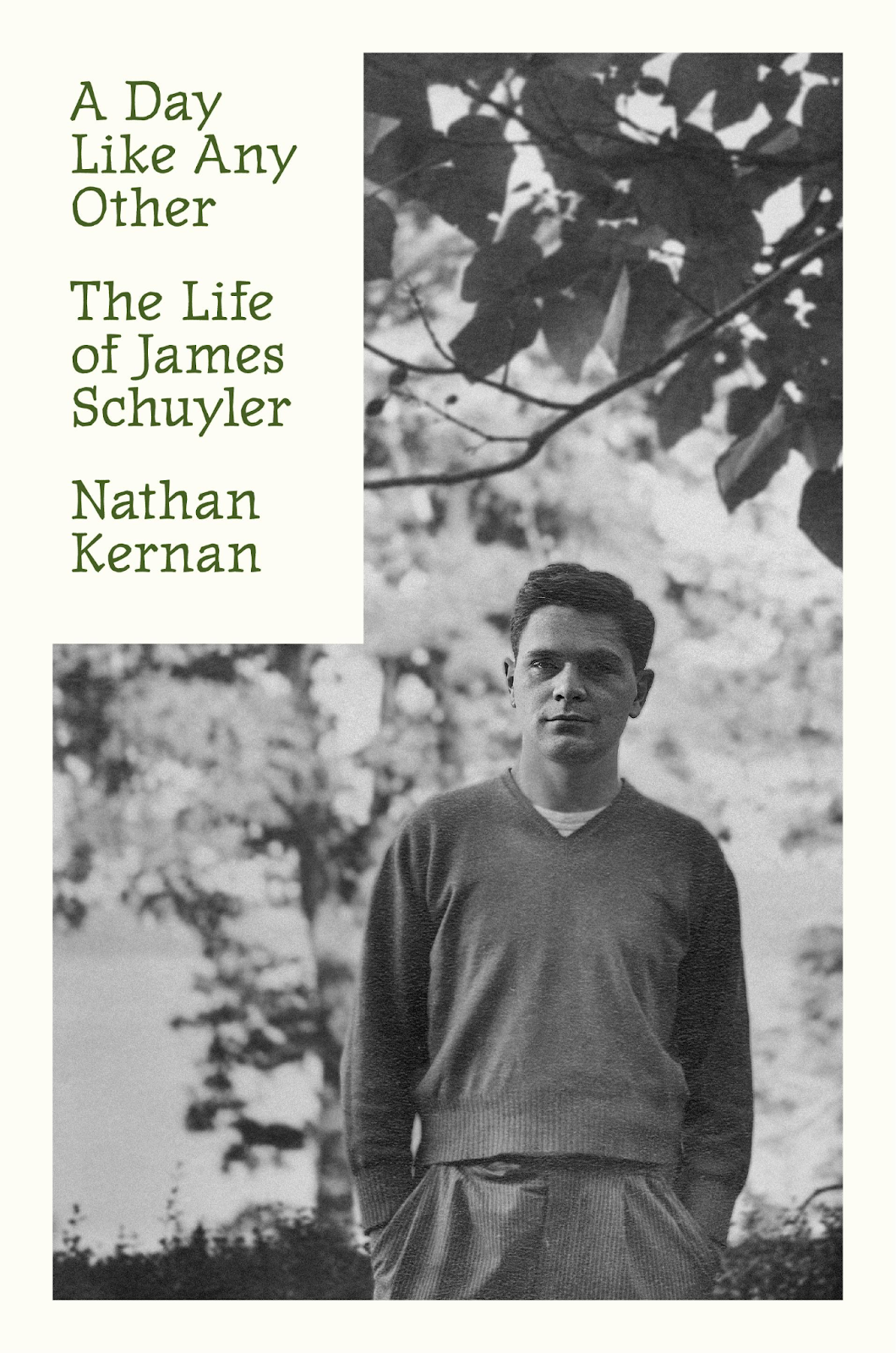

A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler

by Nathan Kernan

From the publisher: Nathan Kernan’s A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler is the definitive biography of the great American poet who, along with Frank O’Hara, Barbara Guest, John Ashbery, and Kenneth Koch, was an original member of the so called New York School of poetry. Opening with Schuyler’s legendary first public reading in 1988, Kernan goes back to trace the tumultuous arc of the poet’s life and work.

Born in Chicago in 1923, James Schuyler grew up in Washington, D.C., and upstate New York before moving to New York City in 1944, where he fell into the social orbit of the poet W. H. Auden. After two years in Italy, he returned to New York in 1949 and began to publish his first poems. There he met fellow poets O’Hara, Ashbery, Guest, and Koch. For many years he lived outside the city in Southampton, Long Island, in a close relationship with the painter Fairfield Porter and his family, and spent his summers in Maine. Schuyler’s subsequent years in New York City were marked by poverty and mental illness, yet it was during this time that he wrote some of his greatest poems. After his move to the Chelsea Hotel in 1979, the poet’s circumstances began to turn around, and when he died, much too soon at sixty-seven, his life was stable and fulfilled.

In praise of Schuyler’s poetry, John Ashbery wrote: “To reread him is to live, as though life were an experience one had just forgotten and been newly awakened to.” Schuyler’s work embodies the quiet beauties of the natural world and the mundane stuff of everyday existence, even as his own life was often messy and troubled. A Day Like Any Other, Kernan’s absorbing biographical study, explores this and other paradoxes of Schuyler’s singular life within the vibrant milieu of mid-century New York’s poets and painters.

[We linked to a review in WRB—July 12, 2025.]

Also out Tuesday:

Seagull Books: Satyajit Ray: A Film by Shyam Benegal

Skyhorse Publishing: Some Recollections of St. Ives: A Novel by David Mamet

What we’re reading:

Steve read more of The Luck of Barry Lyndon.

Critical notes:

Jane Cooper on kingship in Shakespeare’s Richard II:

Given the aforementioned context of the play, to construe the events of Richard II as implicitly supporting elective monarchy as a kind of proto-democratic system would be to take serious interpretative liberties. It would also ignore the tragic flaw at the centre of the action: Richard’s conflation of anointed kingship with absolutism and license to forsake the law of the land. For audiences since those of Jacobean England, Richard’s belief that he exists above the law in the first act, and claims like “The breath of worldly men cannot depose / The deputy elected by the Lord” would have been registered as ironic in the aftermath of the Wars of the Roses. Respect for the monarch as the head of the body politic was strong, trusting that the monarch would be a healthy head atop a healthy body. One important Biblical element to the medieval theories of kingship which persisted well past Elizabeth’s reign was the Pauline construct of a mystical body described in 1 Corinthians 12: “For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ.” In this light, Edward Coke at the case of Proclamations of 1611 asserted that “the King hath no prerogative, but that which the law of the land allows him.”

Jason Scott-Warren on the conversation in which Elizabeth I said “I am Richard II, know ye not that?”:

During the government investigation of Essex’s uprising, it had emerged that his accomplices had paid a theatre company to revive an old play about Richard II on the afternoon before the rising. The play was probably Shakespeare’s Richard II, which focuses on the deposition. In the courtroom, Francis Bacon said that the Earl’s servants wanted to watch a tragedy that their master would soon bring “from the stage to the state.” Elizabeth’s “tragedy . . . forty times played in open streets & houses” can be read as another response to these events, one that registers Shakespeare as a political threat. As Jonathan Dollimore asked, “can ‘tragedy’ be a strictly literary term when the Queen’s own life is endangered by the play?” Lambarde’s conversation with Elizabeth thus not only feels like drama, emulating the cut-and-thrust of stage dialogue. It creates a connection between the texts we consider as literature and those we treat as historical documents. For historicist criticism, there was no fundamental difference between the two; “the textuality of history” matched “the historicity of texts.”

Buku Sarkar on articulating process:

It is important, if only privately, to be articulate about what you are doing and why. As an artist, of any discipline, you have to be able to answer your own questions. Or work towards an answer. Taking a photograph is easy. We can all do it. But to analyze it, rationalize it (yes, as counterintuitive as it feels) is as important as taking the image itself. How else will you grow?

Don’t just pass it off with the “image speaks a thousand words” nonsense because we only say that out of defensiveness.

You know this is true.