WRB—Aug. 24, 2024

“rebuild the Tower of Babel”

THE WASHINGTON REVIEW OF BOOKS IS NOT an idea. It is a radiant node or cluster; it is what I can, and must perforce, call a VORTEX, from which, and through which, and into which, ideas are constantly rushing.

N.B.:

The audio of this month’s session of the D.C. Salon is now available:

The next monthly salon, on the topic “Can we choose our beliefs?”, will take place on September 28. If you would like to attend, please email Chris for the details.

Links:

Two in The Paris Review:

An email exchange between Christopher Bollas and Helen Vendler. Vendler:

Of course, your reflections on everything from stand-up comics to serial killers are fascinating. Who hasn’t pursued comparable characterizations of comic or sadistic apparitions in culture? Your anecdotes (Ken Kesey and the Panthers) offer a moment of relief in the argument of a serious article, and your personal anecdotes are equally attractive on a written page. I often wish that the criticism of poetry offered that sort of relief to the reader, but I can’t manage it, not wishing to be intruding on Keats or Shakespeare. You’re working with human beings in actual life—so different from working with etymological and semantic and syntactic phenomena—but I wish I had your sense of relish of the human comedy (and tragedy). As you say, “A sense of humor . . . captures the intersection of two realities: the intentional and the unintentional— . . . breaking down one’s receptive equanimity upon encountering the ponderous”—and literary criticism is always leaning, if only slightly, in the directions of the ponderous. I love creative writers far more than scholars because of their disruption of the expected: I wish I had their wit. The “ironic fate” of any analytic session in its unwilled disruption of itself is a defense of listening with the third ear, which perceives that fate.

[One thing I noticed over the course of reading thousands of Roger Ebert’s reviews is his tendency to be less funny when he thinks a movie is great (even if the movie in question is itself funny). It’s as if he felt the need to have the tone of the review, through its seriousness, speak to the quality of the movie. Reviewing four movies a week is a different task than poetic criticism, but, if some barely-remembered movie that got four stars can make Ebert stop being funny, is it any surprise that the effect of Shakespeare on the critics of poetry is even more powerful? —Steve]

An excerpt from Giorgio Agamben’s upcoming book (Self-Portrait in the Studio, translated by Kevin Attell, October 6):

One knows something only if one loves it—or as Elsa would say, “only one who loves knows.” The Indo-European root that means “to know” is a homonym for the one that means “to be born.” To know [conoscere] means to be born together, to be generated or regenerated by the thing known. This, and nothing but this, is the meaning of loving. And yet, it is precisely this type of love that is so difficult to find among those who believe they know. In fact, the opposite often occurs—that those who dedicate themselves to the study of a writer or an object end up developing a feeling of superiority towards them, almost a sort of contempt. This is why it is best to expunge from the verb “to know” all merely cognitive claims (cognitio in Latin is originally a legal term meaning the procedures for a judge’s inquiry). For my own part, I do not think we can pick up a book we love without feeling our heart racing, or truly know a creature or thing without being reborn in them and with them.

In our sister publication on the Hudson, Victoria Baena on an exhibit of Brecht’s fragments and extracts:

On the other hand, the delivery drivers zooming on electric bikes past the performance of a play about Weimar-era inequality did recall Brecht’s interest in the analogies and discrepancies between his era and earlier moments of economic crisis and conflict. This was one reason he so often set his plays in a time or place other than his own, from interwar China (The Good Person of Szechwan, 1941) to seventeenth-century Italy (Life of Galileo, 1938). What he called “historicism” was another way of startling viewers into recognizing the specific conditions that shaped their present. A note to Fatzer observes that the play was to be set “at the time of the first world war a time bereft of all morality.” It was to end “with the total destruction of all four [men] but which in midst of murder false witness and debauchery also bore the bloody traces of a new kind of morality.”

In the local Post, Michael Dirda on Lewis Carroll’s poetry:

As is well known, Carroll’s writing revels in wordplay, mathematical patterns and tantalizing verbal suggestiveness. Not surprisingly then, the experience of reading “The Hunting of the Snark” calls to mind Alice’s reaction to “Jabberwocky”: “Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don’t exactly know what they are!” Commentators, some serious, some facetious, many desperate, have argued that the poem allegorizes the pursuit of happiness, or social success, or wealth, or even the Hegelian absolute. Martin Gardner, in The Annotated Hunting of the Snark (2006), strongly contends that its covert subject is the inevitability of death, while some French theorists regard the work as nothing less than an investigation of le néant—the void, nothingness. The Snark hunters themselves can even sound like students of semiotics. Remember that blank map?

[You’re telling me that the covert subject of a literary work is the inevitability of death? Wow. I’ve never heard that before. —Steve]

In Engelsberg Ideas, Alexander Lee on Guercino’s business sense:

Perhaps his most effective secret was copying. During the seventeenth century the art market was extremely competitive. Works by celebrated artists—like Guercino—were in high demand. Patrons often vied to buy the best works; and if they didn’t win, they could either arrange for another painter to make a copy or hold a grudge against the artist for favoring his rival. Either way, the artist risked losing money. Guercino realized that he could avoid this by making copies of his best works. Take Lot and His Daughters (1650). Two years earlier, a certain Girolamo Panessi had bought the Samaritan Woman at the Well (1658) for 113 scudi—and he was now anxious to buy Lot and His Daughters. Unfortunately, Guercino had already sold it to Manzini by then. He didn’t want to disappoint Panessi, either, so when Manzini decided to give the painting to the Duke of Modena, Guercino seized the opportunity to take a look and make a copy. Everyone was happy; and Guercino made money twice over.

Two in The New Criterion: first, Allen C. Guelzo on Charles Ives’ Third Symphony:

Ives has been associated with modernism largely because of the complexity of his musical experiments. But those experiments began with a reach not forward but backward, to his father, George Ives, a Civil War bandmaster and town musical leader in the Ives family’s hometown of Danbury, Connecticut. George Ives implanted in his son Charles a taste for experimenting with sound—with the cacophony of rival bands marching past each other, songs sung to accompaniments in a different key, and amateur church singers whose earnestness in singing gospel hymns was more valuable than their intonation. This was the musical landscape of Charles Ives’ boyhood, and it pointed in no direction that looked “modern.”

[Since college football season starts today, here is Ives’ take on an old drinking song (complete with kazoo chorus) that also inspired the best college football fight songs. (The Notre Dame Victory March excepted, of course.) —Steve]

Reviews:

Second, William Logan reviews a new edition of Delmore Schwartz’s collected poems (The Collected Poems of Delmore Schwartz, edited by Ben Mazer, April):

If there’s a plan in this mishmash of overbaked verse and sub-Whitman prose, it’s not easy to follow—and, when you follow, it’s hard to understand why Schwartz felt obliged to tackle the same tale again and again, to pierce the psychology before and after, Freud’s collected works in hand. Longer with Schwartz was not deeper. He had many gifts, but concision was never among them—poetry is usually stronger when the poet lets the reader make the connections; but Schwartz, like some deranged electrician, left his poems full of backup generators and faulty wiring. He was victim of an inner fury, a tendency to destroy the very thing he was desperate to create. The good notices came from friends, but most reviews agreed that the poem was ridiculously overlong.

Schwartz could write perfectly acceptable pentameter when he wanted, but in Genesis it often sounds like prose padded into verse: “A fiancée; the quintessential flower: / Who better shall draw from the little boy / The first of all the many metaphors / With which he will enact his hope and fear?” His narrative flits from prose to verse and verse to prose without making either seem necessary. Genesis reminds me of The Ring and the Book, which runs longer than either the Iliad or the Odyssey—but Browning, a far better technician than Schwartz, came much closer to writing a credible verse-novel.

[We linked to an earlier piece on Schwartz in WRB—July 17, 2024. “You killed your European son / You spit on those under twenty-one.” —Steve]

In The Nation, David Schurman Wallace reviews a reissue of a Guy Davenport essay collection (The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays, 1997, January)

If “imagination” is the key to Davenport’s thinking on culture, he did not mean it in the way that it is often invoked today: a disruptive idea that strikes like a bolt from the blue. Tradition was indispensable, even inescapable, in the act of creation, he believed. In one of the collection’s most famous essays, “The Symbol of the Archaic,” Davenport provides another axiom of his thought: namely, that modernism needed to look backward, deep into the past, to advance. “What is most modern in our time frequently turns out to be the most archaic,” Davenport writes. “The sculpture of Brancusi belongs to the art of the Cyclades in the ninth century B.C. Corbusier’s buildings in their Cubist phase look like the white clay houses of Anatolia and Malta.” If The Geography of the Imagination asks us to think spatially or cross-culturally, Davenport here asserts the power of the “midden” of history, what he sees as the twentieth century’s reabsorption of the past to create new, more vital work: “Archaic art, then, was springtime art in any culture.”

[We linked to the reissue’s introduction and a review in WRB—Jan. 13, 2024 and another review in WRB—July 27, 2024. Today’s opening joke, which came to me after reading the second review and which, like many of the opening jokes, is mostly true, has been in my mind as a kind of WRB mission statement ever since. The purpose of rounding up what gets rounded up here and then commenting on it (both through notes like this and the structure of the newsletter itself) is to bring the old and the new together (I had some notes on this last month) and suggest connections—to get the ideas rushing, as it were. —Steve]

In our sister publication on Lake Erie, Cary Stough reviews Kate Briggs’ notes on translation (This Little Art, 2017), a translation of poetry by Ann Jäderlund (Lonespeech, translated by Johannes Goransson, May), and a collection of “translations” by Jacqueline Feldman (On Your Feet: A Novel in Translations, March)

The anxiety of authorial influence in the art of translation remains partly immanent to translators themselves, the myths they’ve kept alive about the task precisely by their perennial self-criticism. “The hidden masters of our culture,” Maurice Blanchot called them, and that has always stuck. But I wonder, is part of that avowed hiddenness not what defines this as cultural work at all? Precious few literary artists get the validation Blanchot bestowed upon the translator: “the enemy of God,” who by the act, “seeks to rebuild the Tower of Babel.” This seems to be a common trope among the canon of critical literary theorists. The valorization of the act persists, it appears, because no one—not even God—has convincingly absolved us of our Babelian guilt. In every translators’ note there is a melancholy nostalgia for the harmony we squandered by once being, in those brief moments at the top of the tower, too close to heaven. In the incongruity between languages, also known as misunderstanding, there’s an acknowledgment of a kernel in each lexicon that resists transfer. And in each attempt to smooth out a translated work’s re-telling, there’s an admission of faith in the originality of the author’s text. If we’ve learned anything from Kierkegaard, we know that faith is only fulfilled in its tumbling down. We know from Marx, that faith follows funding.

In The New Republic, Anna Altman reviews a book about hypochondria (A Body Made of Glass: A Cultural History of Hypochondria, by Caroline Crampton, April) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Apr. 17, 2024.]:

Crampton seeks out these stories to identify “fellow travelers,” as she puts it, but in each of these examples, how was the notion of hypochondria helpful to the sufferer? Some dwelled on illness because it had indeed shattered their lives (Donne lost his father, three sisters, a brother, a stepfather, four children, and his wife in untimely fashion), and expressing fear of illness gave voice to a defining part of his life, while others, like Molière, who engaged medical professionals to no avail, may have dramatized the experience to balance his anxiety with levity. Others, like Kant, used the term to regain a sense of control over the body. Later, Freud’s preoccupation with the unconscious mind established the idea that health problems were either physical or mental, but that one could indeed influence the other. Hypochondria, in these instances, is not pure pathology but serves a purpose: It expresses our fundamental mortality, or a theory of mind or body.

[Cf. the pieces about disease in WRB—July 15, 2023.]

N.B. (cont.):

Some really nice covers from long-gone magazines.

The WRB’s friends at the Philosophy & Society Initiative of the Aspen Institute are hiring a Program Associate, part- or full-time in Washington, D.C.

“A burglar who broke into an apartment in Rome on Tuesday night was arrested after stopping in the middle of the robbery to read a book about Greek mythology.” [Sir, subscribe to the Washington Review of Books. —Steve]

New issues:

The New Criterion Volume 43, Number 1 / September 2024 [As linked to above.]

Poem:

“Greeter of Souls” by Deborah Digges

Ponds are spring-fed, lakes run off rivers.

Here souls pass, not one deified,

and sometimes this is terrible to know

three floors below the street, where light drinks the world,

siphoned like music through portals.

How fed, that dark, the octaves framed faceless.

A memory of water.

The trees more beautiful not themselves.

Souls who have passed here, tired, brightening.

Dumpsters of linen, empty

Gurneys along corridors to parking garages.

Who wonders, is it morning?

Who washes these blankets?

Can I not be the greeter of souls?

What’s to be done with the envelopes of hair?

If the inlets are frozen, can I walk across?

When I look down into myself to see a scattering of birds,

do I put on the new garments?

On which side of the river should I wait?

[This is from Digges’ Trapeze (2004), her fourth collection out of five (counting her posthumous The Wind Blows Through the Door of My Heart).

I’m so often fascinated by Digges’ ability to handle strange, complex syntax (like in the earlier poem of hers we featured back in February), and I see that here, although tightened into such short sentences like The trees more beautiful not themselves. What really strikes me about this poem, though, is the way she uses man-made materiality to depict her idiosyncratic recreation of the Greek underworld: one of the first things we’re told is that it’s three floors below the street. I love how that description frames something inherently mysterious and beyond comprehension within a setting that’s both extremely ordinary and unappealing—Hell, Digges tells us, is just like a parking garage. Other, similar details build upon this: the dumpsters of linen, the dirty blankets, the envelopes of hair. It’s all dirty and human, and yet we get moments that run up against those descriptions: the souls that, though tired, brighten; the trees that become more beautiful as they become more othered from their natural state; the scattering of birds in the speaker’s chest.

I love that last line, which holds its own mystery within it—When I look down into myself and see it, she asks, do I put on the new garments? There’s so much tension there, and hope, too—the fact that the new garments are, it’s implied, within reach already, just hanging somewhere nearby while the speaker waits for a sign to put them on. The final line, too, has a beautiful tension in the way it looks toward the physical distance of the two river backs. On which side of the river should I wait, before the souls forget their earthly lives, or after? —Julia]

Upcoming books:

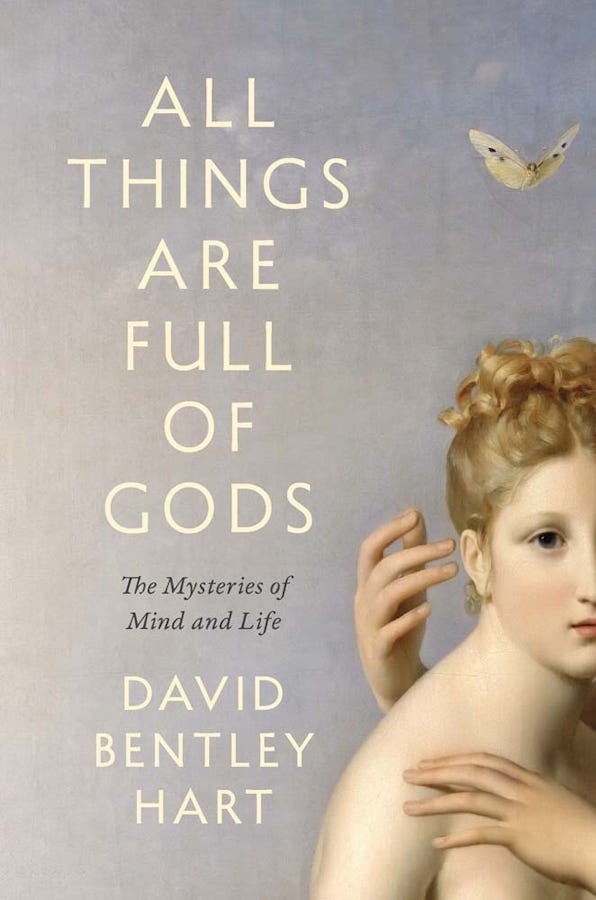

Yale University Press | August 27

All Things Are Full of Gods: The Mysteries of Mind and Life

by David Bentley Hart

From the publisher: In a blossoming garden located far outside all worlds, a group of aging Greek gods have gathered to discuss the nature of existence, the mystery of mind, and whether there is a transcendent God from whom all things come. Turning to Eros, Psyche asks, “Do you see this flower, my love?”

. . . .

Engaging contemporary debates on the philosophy of mind, free will, revolutions in physics and biology, the history of science, computational models of mind, artificial intelligence, information theory, linguistics, cultural disenchantment, and the metaphysics of nature, Hart calls readers back to an enchanted world in which nature is the residence of mysterious and vital intelligences. He suggests that there is a very special wisdom to be gained when we, in Psyche’s words, “devote more time to the contemplation of living things and less to the fabrication of machines.”

Also out Tuesday:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: Christopher Isherwood Inside Out by Katherine Bucknell

Harvard University Press: Simone Weil: A Life in Letters, edited by Robert Chenavier and André A. Devaux, translated by Nicholas Elliott

Wise Blood Books: The Blackbird & Other Stories by Sally Thomas

Yale University Press: Tchaikovsky’s Empire: A New Life of Russia’s Greatest Composer by Simon Morrison [We linked to a review in WRB—Aug. 3, 2024.]

What we’re reading:

Steve finished the essays on the English Civil War. Seeing It Ends with Us (August 9) last week prompted him to finally get around to Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature (by Janice A. Radway, 1984) so he can understand what is going on there. [Chris had some notes about it in WRB—Jan. 20, 2024, and we linked to a piece indebted to it in WRB—Apr. 6, 2024.]

Julia started Mariah Stovall’s debut novel I Love You So Much It’s Killing Us Both (February) solely on the basis of the title and the jacket copy’s references to punk music but now can’t put it down. She’s also been reading Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth (1991) and Gerald Manley Hopkins’ Poems and Prose: Selected and edited by W. H. Gardner, and reading poems from Graywolf Press’ anthology Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Poems (January) out loud to her students this week.

Critical notes:

Benjamin Compaine (quoted by Radway while discussing book marketing strategy):

The toothpaste equivalent [of what publishers attempt] would be if Lever Bros. came out with a different brand each month, changing the flavor, packaging, and price, with each new brand having a maximum potential sale to only 4% of the adult population.

To offer a theory though, I think what lasts is almost always what has a dedicated following among one or more of the following: artists, geeks, academics, critics, and editors. “Gatekeepers” of various types, if you like. Artists play the most important role in what art endures because artists are the ones making new art. Indirectly, they popularize styles and genres and make new fans seek out older influences. Directly, artists tend to tout their influences and encourage their fans to explore them. In literature that takes the form of essays, introductions to reissues, and so forth. In music, it might be something like cover albums as in the way Nirvana’s Unplugged (1994) introduced a new generation to older bands and musicians. Academics is pretty obvious. The older books with the best sales are mostly ones that appear on syllabi. And geeks and critics are the ones who extensively explore a genre or category’s history and proselytize their favorites. Editors are the ones who actually chose the older books to republish and can champion obscure books back into the public eye.

[It’s the guys at NYRB Classics. More lasting than bronze. —Steve]

Paul Franz on learning to think:

Might not the primordial question be, not a seeking (by oneself, for oneself) but a requesting? The child wants something. The child demands it. The parent is presumed to possess this, or at least to be able to furnish—to be—the means by which this thing can become the child’s. The thing may be knowledge, but is more likely to be an object—something to play with, something to eat. Do not those metaphors, scarcely metaphors, of “grasping,” and so on, in their root form aim at “possessing,” even the most elemental—the most alimental—form of possessing in eating, consuming?

Alexander Bain and William James first used the phrase “stream of consciousness” in 1855 and 1890, respectively. Literary critic May Sinclair was the first to deploy it in a literary context, using it in The Egotist in April 1918 to describe Richardson’s ability to get “closer to reality” through “Miriam’s stream of consciousness.” Richardson herself disliked and distanced herself from it, dubbing it, very unflatteringly, a “lamentably ill-chosen metaphor.” She disowned the term, so it abandoned her in turn.

Today, “stream of consciousness” is usually applied to the output of writers such as James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Woolf. Richardson, whose books never achieved the same notoriety as those of this all-star group, is often left out of the conversation, even though she effectively pioneered the method. The question now is, how do we properly recognize her contribution? Do we respect her ardent wish to be detached from the phrase, or do we hail her as the founder of a modernist movement that defined a generation? This, like the business of trying to decipher a lengthy paragraph of unbroken psyche, is a tricky one.

For generations, academics and critics have been trying to sever American letters from the broader inheritance of the Western canon. In his book America’s British Culture (1993), Russell Kirk took narrow-minded multiculturalists like Folta and his ilk to task and insisted that Americans should lay claim to the great body of English literature. “Love of an inherited culture has the power to cast out the envy and hatred of that culture’s adversaries,” he wrote. That’s a far superior approach to our literary heritage, and I can think of no better author to teach that kind of love than the ever-delightful and utterly lovely Jane Austen.

[You have to read Whitman, but you also have to read all the other stuff. Great harm has been done by Americans who only did the first half of the assignment. —Steve]

What is “striking” about Genesis 1, from the perspective of the cultures that surrounded Israel, is the “demotion of the sun” from divine status to, effectively, a big light in the sky—just another of the things created by YHWH. That is, the primary dialectical strategy of Genesis 1 is disenchantment.

Even Max Weber, the man to whom we owe the phrase “disenchantment of the world,” spoke of the resident of disenchanted modernity as being trapped in an “iron cage of rationality”—which sounds rather like the condition of someone under a dark enchantment. I think of “the man in the iron cage” in Pilgrim’s Progress—did Weber know that scene?