WRB—Aug. 27, 2022

MGMT Editors

That’s the WRB painted on the wall, looking as if it were alive.

To do list:

Follow us on Twitter [Or Instagram. Or Facebook.] to keep up with the Barely-Managing WRB Summer Intern;

Order a tote bag;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, now stored on this page for non-paying readers to access, either by placing or responding to one;

and,

Links:

The Italian Proust?

Harrison Dietzman explains the inavoidability of smoke in The Point.

In First Things, Jason M. Baxter revisits The Wasteland at 100.

The Atlantic has a new project that takes its cues from Calvino and Nabokov: “This month, The Atlantic is excited to present five shorter stories displaying the virtue of lightness. Through a diversity of style, voice, and perspective, these writers build worlds with precision and economy, speaking to love, belief, loss, and, most important: possibility.”

Reviews:

Ian Beacock in The New Republic examines a British mid-century study of people who thought they could see into the future: “Most of us have experienced odd coincidences that make us feel, even for an instant, that we have glimpsed the future. A phrase or scene that triggers a jarring sensation of déjà vu. Thinking of someone right before they text or call. Inexplicably dreaming about a long-lost acquaintance or relative only to wake and find that they have fallen ill or died. It’s mostly accepted that these are not really forms of precognition or time travel but instead fluky accidents or momentary brain glitches, explainable by science. And so we don’t give them a second thought or take them that seriously. But what if we did?”

In the Baffler, John Merrick reviews Terry Eagleton’s survey of five “Critical Revolutionaries.” “The one unifying feature of each of these writers, then—or at least the first four—is their deep cultural pessimism. The picture they paint of British culture is one of diminished standards, wracked by the rise of a mass culture in thrall to Americanized entertainment—what Richards hyperbolically called “the sinister potentialities of the cinema and the loud-speaker.” This cheapening of culture wasn’t merely a decline in the field of art, but was taken by the critics as a symptom of a declining society.”

N.B.:

The Week is looking for a weekend staff writer.

Astra is accepting submissions.

Bright Lights, Big City, Niche Fame [Who comes up with these headlines? Story of my life. –Nic]

The first White Noise trailer is, uh.

Heroes of the Fourth Turning is coming to Washington.

Dean Young, former Texas poet laureate, has passed away.

The staff of the Paris Review shares their favorite sentences. [A few of my favorites: “Later, when Sandy read John Calvin, she found that although popular conceptions of Calvinism were sometimes mistaken, in this particular there was no mistake, indeed it was but a mild understanding of the case, he having made it God's pleasure to implant in certain people an erroneous sense of joy and salvation, so that their surprise at the end might be the nastier.” —Muriel Spark, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie; “People bind themselves into numbered seats and fly across time zones and high cirrus and deep night, knowing there is something they’ve forgotten to do.” —Don DeLillo, Mao II; “Taco Bells jumped out at her.” —Joan Didion, Play It as It Lays —Nic]

Upcoming book:

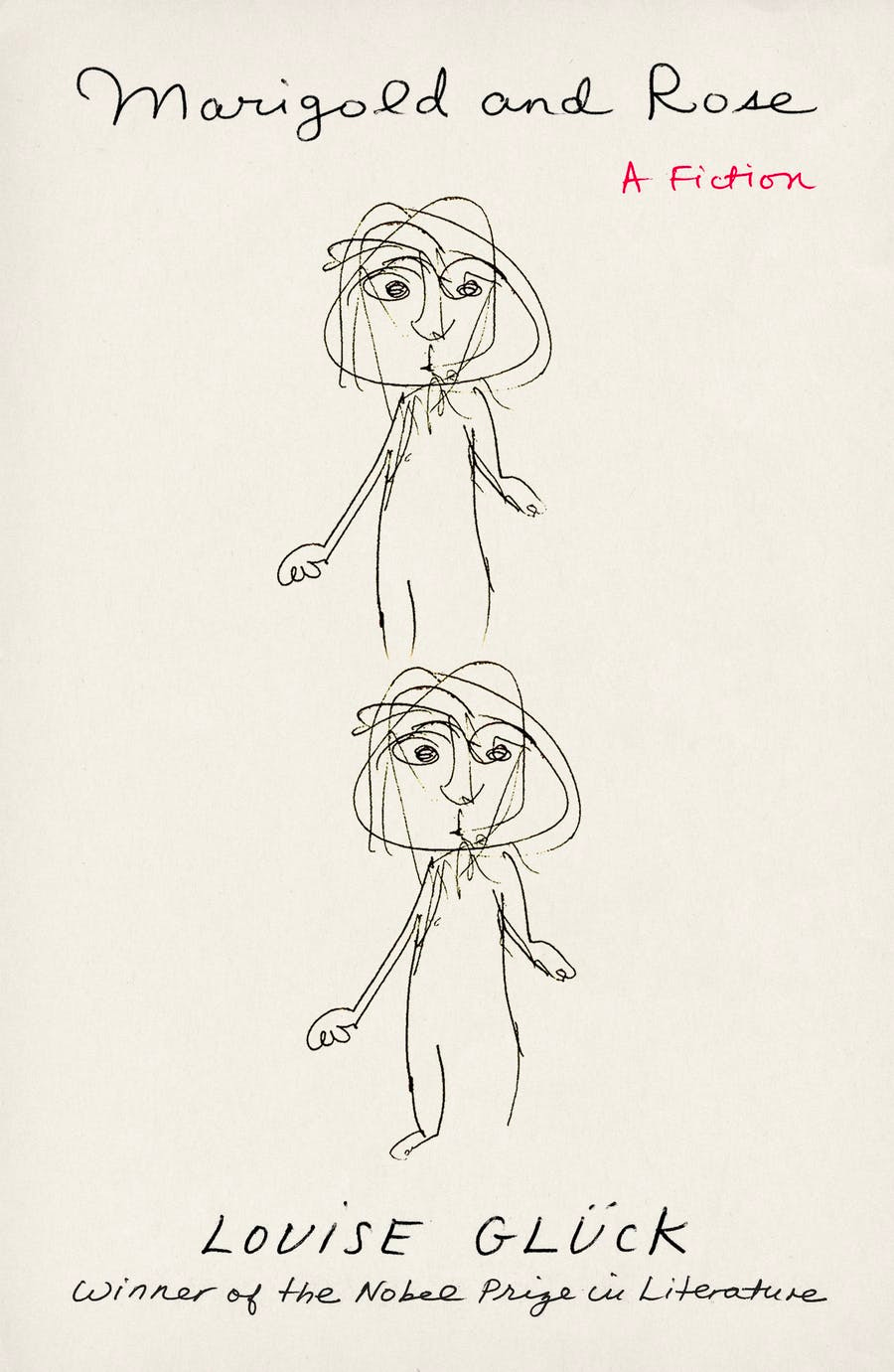

October 11 | Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Marigold and Rose

by Louise Glück

From the publisher: Marigold and Rose is a magical and incandescent fiction from the Nobel laureate Louise Glück.

“Marigold was absorbed in her book; she had gotten as far as the V.” So begins Marigold and Rose, Louise Glück’s astonishing chronicle of the first year in the life of twin girls. Imagine a fairy tale that is also a multigenerational saga; a piece for two hands that is also a symphony; a poem that is also, in the spirit of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, an incandescent act of autobiography.

Here are the elements you’d expect to find in a story of infant twins—Father and Mother; Grandmother and Other Grandmother; bath time and naptime—but more than that, Marigold and Rose is an investigation of the great mystery of language and of time itself, of what is and what has been and what will be. “Outside the playpen there were day and night. What did they add up to? Time was what they added up to. Rain arrived, then snow.” The twins learn to climb stairs, they regard each other like criminals through the bars of their cribs, they begin to speak. “It was evening. Rose was smiling placidly in the bathtub, playing with the squirting elephant which, according to Mother, represented patience, strength, loyalty, and wisdom. How does she do it, Marigold thought, knowing what we know.”

Simultaneously sad and funny, and shot through with a sense of stoic wonder, this small miracle of a book follows thirteen books of poetry and two collections.