WRB—Aug. 30, 2025

“fizzy little plot”

The Washington Review of Books is running misprints and clumsy wordings from other publications, and otherwise being Godlike, so WE MUST BE DAMN NEAR PURE OURSELF.

Links:

In our sister publication on the Hudson, Adelle Waldman on what happened to the suburban novel:

Though it both defined and anticipated the form, Babbitt (1922) differs from the suburban novels of the midcentury in one crucial way: it is satirical, veering between a send-up of Babbitt’s boobism and self-flattery and an occasionally sympathetic portrait of a man who is trapped in a life he doesn’t quite like. Unlike the heroes of later suburban novels, Babbitt, a well-to-do businessman with a college degree, wasn’t presented as an everyman. Rather, he seemed to represent an up-and-coming type—what we’d later call a member of the professional middle class. As Babbitt says in a boosterish speech to his fellow businessmen, “It’s the fellow with four to ten thousand a year, say, and an automobile and a nice little family in a bungalow on the edge of town, that makes the wheel of progress go round!”

By the time the suburban novel reached its apotheosis, Babbitt’s comfortable, thing-filled lifestyle had come to be associated with the average American, or what was assumed to be the average American by many writers and critics and readers. This was essential. Even if many suburban novels focused on characters in the upper strata of the middle class—one exception being Rabbit Angstrom, a former high school basketball star who works a lower-middle-class sales job hawking a kitchen gadget called the MagiPeeler at a local department store—they were nonetheless portrayed not as economic winners in an exploitative system but as ordinary people: not satirical targets but deserving of the sympathies of a mass audience.

[Waldman mentions The Ice Storm (1997) and American Beauty (1999) when talking about a later wave of art about the suburbs that came after the novels of the 1950s and early 1960s, but she omits the likes of Office Space (1999) and Fight Club (also 1999). Relatedly, her analysis of how the changing economic situation shaped this art, though accurate, glosses over the change in America’s self-conception. The characters wondered, to quote Peggy Lee, “is that all there is?” in very different Americas.

The ’50s have entered cultural memory wrongly simply because the Boomers, with their vast numbers, were children then. It was not a prelapsarian idyll. It was a time when the nation was trying and mostly failing to reckon with the Second World War. I mean this in both the most immediate sense—with those who died, with those who came back permanently wounded, whether physically, mentally, or spiritually—and in a broader one. Some of the questions were more philosophical; for example, what did the Holocaust reveal about civilization and barbarism? Some were more practical, like wondering how to return to something like normal after the upheavals caused by four years of war economy on the home front (and before that the Great Depression). And over all of this hung the knowledge that the two global superpowers, struggling for geopolitical and ideological supremacy, had weapons pointed at each other which could end the world. The stifling suburban conformity of the 1950s depicted in the novels Waldman discusses did not come from a place of confidence. It was a desperate attempt to conjure up and cling to something that seemed stable and safe after the Second World War and its aftermath had shown that nothing could be taken for granted.

The 1990s were not plagued by these doubts. The idealized American way of life was not something new and fragile, created to ward off the wolves. It was (to invoke a book far more subtle than its detractors admit) the only thing left at the end of history. The Cold War was over, and the United States won; from now on it would be liberal democracy and free-market capitalism in saecula saeculorum. And so, unlike in the 1950s, to question whether this was all there is was not to push against a hastily assembled idea of stability; it was to question what history was and how it worked.

The particular complaints may not have held up. I have heard plenty of commentary about ’90s suburban movies from people my age amounting to “what are these guys so worked up about? I wish I had a house in the suburbs and a stable and well-paying office job.” But, just as the suburban novels of the ’50s pointed to how that vision of normality would come apart in the next decade, the suburban novels and movies of the ’90s asked a question we are still asking: what about thymos? —Steve]

In The American Scholar, Thomas Swick on the revival in travel writing brought about by Paul Theroux’s The Great American Bazaar (1975):

In Istanbul, Theroux spends a day with the writer Yashar Kemal, and this outing takes up more space than his visits to the Topkapi Palace and Hagia Sophia. For him, sightseeing is “an activity that delights the truly idle because it seems so much like scholarship”; he’s much happier, and more productive, talking to people—a practice he would later in his career describe as “buttonholing”—and attentively walking the streets, where the “hairy brown sweaters and argyle socks” suggest to him that the city has stood still since the death of Atatürk in 1938.

Sort of like travel writing. Most travel writers who visited Istanbul before Theroux wrote, as if by some unwritten professional decree, about the history and the architecture, the restaurants and hotels (with the obligatory nod to the Pera Palace and Agatha Christie); no one mentioned the hairy brown sweaters. Presumably they saw them, provided their heads weren’t buried in guidebooks, but they viewed them as insignificant compared to the treasures of the Topkapi jewel room. The problem was, the jewels had already been written about; the past was a well-covered, pawed-over subject. Few people wrote about the Turkey of their time. And it was Theroux’s great talent to be able not only to home in on a sartorial detail that vividly brought the Turks to life—and put his readers there on the streets with them—but to glean from it a valuable insight.

[Pictures of exotic places being available on the Internet, instead of being the exclusive province of National Geographic and the like, probably did a lot to do in travel writing as well. —Steve]

Reviews:

In The Bulwark, Mary Townsend reviews Agnes Callard’s book about Socrates (Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life, January) [An Upcoming book in WRB—Jan 11, 2025.]:

But “letting” someone help you make brownies is not real recognition. And one reason compliments are often awkward to give and receive is because they never can be mutual, quite. Absent in this tale of cookery is any moment of mutual noticing, any sign of mutual, lasting respect, because these are things that mind-direction, flattery, and being treated as “an intellectual thing” cannot give. Ultimately, Callard’s Socrates remains Callard herself, both king and sister, and what lies beneath the avatar, the most real thing of all, is just this ambition and, as she identifies, a longing that is “perpetually dissatisfied”—contentless, hungry, with a heartbreakingly contradictory desire to rule the world and yet remain somehow lovable, both a tyrant and a good little girl, a kind of ravenous little mermaid of the soul, where Socrates is the animated crab. Yet fortunately for the rest of us, attaining mastery over someone else’s will is not the only thing that gives human beings worth; and, gods be praised, we remain much more than minds.

And I have known the eyes already, known them all—

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

In a book about Socrates it’s striking that this is not a story about dialogue. —Steve]

In Engelsberg Ideas, Katherine Harvey reviews a book about the moon (The Medieval Moon: A History of Haunting and Blessing, by Ayoush Lazikani, September 9):

Medieval writers also imagined what might happen if Moon-dwellers came to Earth. Some of these fantasies were rather sinister: Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain included stories of incubus demons who frequently travelled back and forth between Earth and the Moon, when they were not busy having sex with human women. But others, such as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, are rather moving. In this tenth-century Japanese story, an elderly couple find and raise a tiny child. She grows up to be a beautiful young woman, loving and popular; even the Emperor becomes her friend. But things are not as they seem, for Kaguya-hime is a Moon-princess, and soon her people arrive to rescue her from this “filthy place.” Carrying her off in a silk-canopied chariot, they drape her in a feather robe which makes her forget her earthly friends, so that she cannot remember those who grieve for her.

[Several items in this review would suggest that the medieval mind was quite different from ours. Then I read that in the twelfth century a guy was imagining extraterrestrial beings visiting Earth to have sex with human women, and I concluded that nope, they’re just like us. —Steve]

In the Journal, Donna Rifkind reviews a reissue of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (by Anita Loos, 1925, August 5):

Between the lines of this fizzy little plot is the point that makes Gentlemen Prefer Blondes as fresh today as it was in 1925: This is a story about business that’s pretending to be a story about sex. Or, more exactly, it’s about sex stripped of sentiment to reveal what Loos sees as the pure spirit of transaction at its core. “I always seem to think that when a girl really enjoys being with a gentleman, it puts her to quite a disadvantage and no real good can come of it,” Lorelei confides. Within this frame, Loos levels the playing field. Instead of disparaging her characters as gold diggers and sugar daddies, she portrays Lorelei and her paramours as equally determined to win in a Hobbesian race for acquisition. In the process, rules are upended and everyone resorts to larceny. What could be funnier—or more American?

[I’ve always thought that “everything is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power” would be funnier if instead of “power” it was “money.” (You sometimes see this attributed to Oscar Wilde but he definitely didn’t say it.) Among other things, that way it would naturally set up “you might think he loves you for your money, but I know what he really loves you for—it’s your brand-new leopard-skin pill box hat!” There are layers to this thing.

And, for all the thinkpieces about what’s wrong with dating nowadays, no one has yet been so bold as to pull Leviathan off the shelf:

And therefore if any two men desire the same woman, which neverthelesse they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies; and in the way to their End, (which is principally their owne conservation, and sometimes their delectation only,) endeavour to destroy, or subdue one an other.

—Steve]

N.B.:

The quest to get a review copy of Virginia Woolf’s uncollected letters (The Uncollected Letters of Virginia Woolf, edited by Stephen Barkway and Stuart N. Clarke, March). [One thing that baffles me, as one of America’s leading readers of book reviews, is what gets reviewed and what doesn’t. One thing that especially baffles me is what gets reviewed in eight different places and what doesn’t. Oliver Soden, the author of this piece, claims to have seen exactly one review of the collection, in Literary Review; it’s also the only review of it I’ve seen. As he says:

This, you might think, would still excite what remnants of the literary world there are left, and bears repeating: Edinburgh University Press has published 50 new letters from Virginia Woolf to T. S. Eliot, the lion and unicorn of modernist writing in English.

And in that review Zoe Guttenplan writes:

To Eliot, she compares the sight of Jupiter to “a drop of water under a magnifying glass—all writhing worms” and describes prose (as opposed to poetry) as a “mere frivolity one laps up in a second with one’s tongue.”

No one besides Literary Review thought this was worth a review? It would have been worth it for “writhing worms” alone. —Steve]

The quest for novelty merch at a baseball game. [Last week the Journal had a piece about people attempting to have nine beers and nine hot dogs in the nine innings of a baseball game, which seems like a quest much more in keeping with the spirit of watching—and, for that matter, playing—baseball. —Steve]

The quest to get good at golf in order to hang out with one’s friends. [Is fishing too déclassé? Am I not helping the cause of fishing, the traditional way to waste time with friends while occasionally doing something physical, and one much more open to all classes of society than golf, by associating it with a word that has two acute accents in it? —Steve]

Blue dragons, sea slugs with painful stings, are washing up on Spanish beaches.

Radio stations all over the world.

Poem:

“Drought” by Claudia Emerson

I began to understand

its severity when glassycrows came shameless, panting at last

to the birdbath, and when the locustsfell to the ground, another failed

crop. The street lay empty all day,and the river grew thinner, its spine

showing through. Only butterfliesthrived—the still air cleft by their

repeating patterns, the featheringwings of swallowtails, monarchs;

I learned from their bright emersionto rely, for a while, only

on the eye, the dry horizon.

[Emerson has an impressive eye for her surroundings and for its minute devastations, like the bite of the drought or the failure of the crops. Nevertheless, the vignettes in this poem startle: the crows rendered shameless by dehydration, the river starved of water. Butterflies are often symbols of death and, as the centerpiece of this poem, they are the participants at a wake in the aftermath of the drought’s enervating scythe. —K. T.]

Upcoming books:

Library of America | September 2

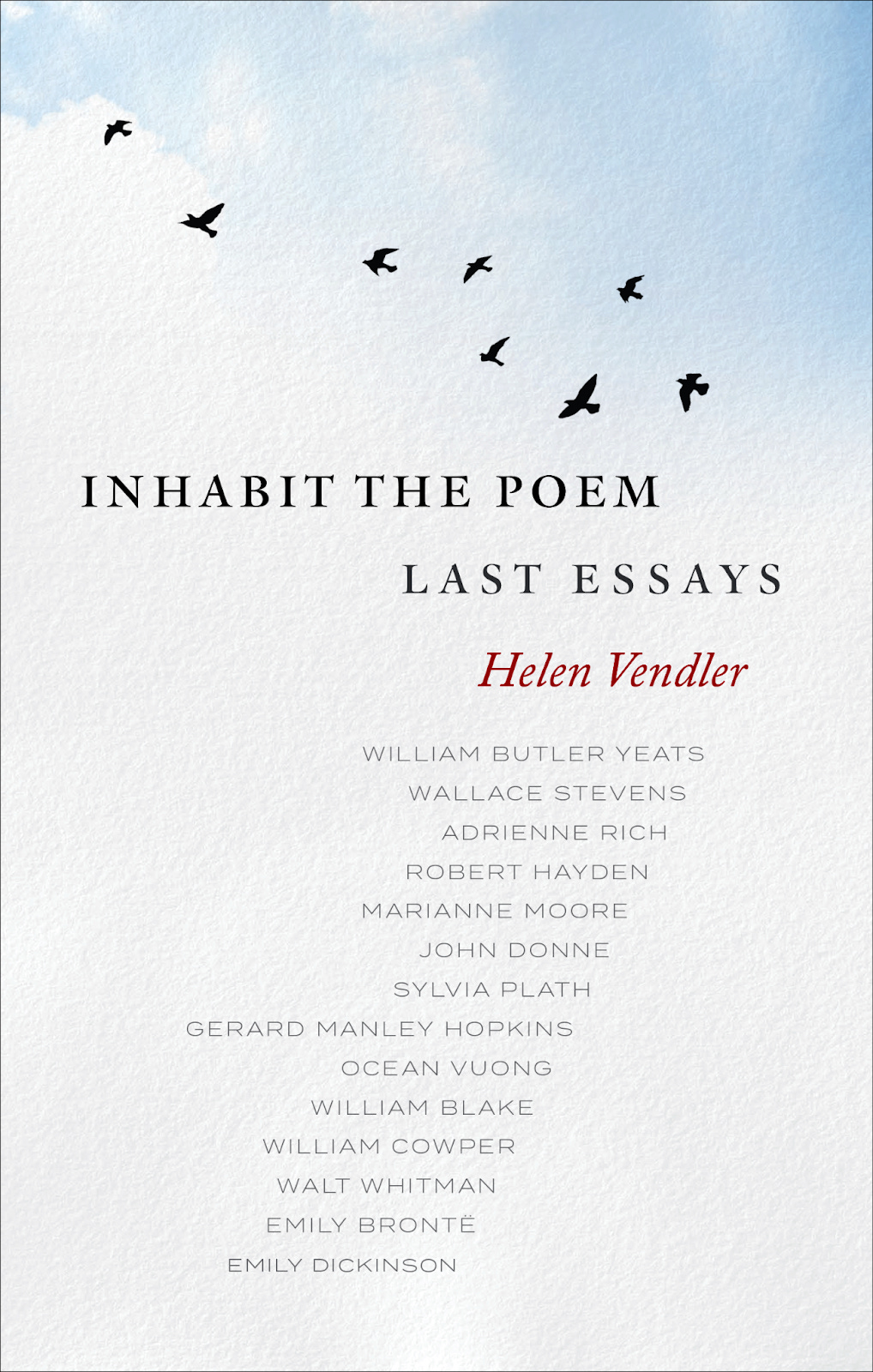

Inhabit the Poem: Last Essays

by Helen Vendler

From the publisher: In this posthumous gift to poetry lovers, one of our foremost poetry critics revisits the work of a wide range of American, English, and Irish poets—from John Donne to Marianne Moore to Ocean Vuong—in thirteen insightful essays. Helen Vendler approaches each of her subjects through the lens of a single poem, inhabiting it, living completely within its world, to uncover its rich emotional life.

The essays gathered here were published in Liberties magazine during the last three years of Vendler’s life, and were intended as her final book. The author’s preface—completed only three days before her death, at age ninety—serves as a summation of her thoughts on poetry and poetry criticism. Whether reflecting on a Black poet’s interest in creating the mind and language of an extraterrestrial (Robert Hayden), on the poetics of motherhood (Sylvia Plath), on the first PTSD poem (Walt Whitman), or on a literary conundrum (why, of the many poems known to her, Emily Dickinson requested on her deathbed that Emily Brontë’s “No coward soul is mine” be read at her funeral), Vendler demonstrates why the Nobel Prize–winning poet Seamus Heaney called her “the best close reader of poems to be found on the literary pages.”

This farewell volume is further testament to Vendler’s remarkable ability to get to the heart of a poem, to reveal the mind of the poet in the act of creation, and to show us exactly why and how poetry matters.

Also out Tuesday:

Assembly Press: The Orange Notebooks: A Novel by Susanna Crossman

Pantheon: The Season: A Fan’s Story by Helen Garner [We linked to a review in WRB—Mar. 26, 2025.]

Unnamed Press: Zone Rouge: A Novel by Michael Jerome Plunkett

Yale University Press: Perpetua: The Woman, the Martyr by Sarah Ruden

Storyteller: The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson by Leo Damrosch

What we’re reading:

Steve read more of The Faerie Queene.

Critical notes:

In The New Yorker, Zach Helfand on the history of fact-checking at that magazine:

Perhaps the most revered of all checkers was Martin Baron, who put in thirty-six years. Baron was gentle, fatherly, and prim. Alex Ross once wrote a piece mentioning a minor Mozart canon titled “Leck mich im Arsch.” Baron stayed up late combing through Mozart biographies so he wouldn’t have to call a Mozart scholar and repeat the phrase “lick me in the ass.” He was almost pathologically punctilious. The checkers loved Baron. He’d bestow upon them honorifics, as in Professor Seligman or Dr. Kelley. He felt that, as a checker, he should avoid errors at all times. John McPhee said, “Somebody told me, ‘The thing you’ve got to know about Martin Baron, he is always right. And take that literally.’ If a Shakespeare play was mentioned in a piece, he would have to go and check the author’s name.” By the end, he’d spent so much time checking that he had difficulty making any assertions at all. He would phrase statements as questions: Wouldn’t you say it’s a nice day? After Baron’s death, Ian Frazier recalled, “Gesturing to the water below the window, he once said to me, ‘I think that’s the Hudson River.’ ”

BDM on Robert Heinlein:

There’s a Tumblr post that lives on in my memory, but which I can never find when I look for it, where somebody sarcastically describes a certain tendency as people saying, basically, “normalize being normal.” In other words, you know, you feel a bit defensive about doing something “normal” and you make that other people’s problem.

“Normalize being normal” is also beginning to describe my mental relationship to Robert Heinlein, in the sense that he is this enormously popular and beloved writer who I nonetheless feel a bit dangerous for liking to read. I act about Heinlein like somebody who has discovered black lipstick exists: Oh, is this too much for you? Is this too much edge, mom?

[I don’t know about describing things as normal—if you want to see where that leads you, you can read a Sally Rooney novel—but it’s certainly preferable to the world where grown adults fight about whether this or that is “punk.” We can’t be happy unless we think that somewhere out there our happiness is making someone mad. —Steve]

In The Point, Steve on the American dream of college football:

Here is something so obvious it hardly needs to be said: all the college football players are in college. They are all, with the exception of the occasional thirty-year-old Australian punter, young. College football is not like the pro sports in this respect. We never see anyone grow old or decay. We never see a player who used to be great reckon with his body very slowly betraying him. We never see anyone washed up. We never see some young kid demonstrate, through his athletic ability, that the game has passed a man on the verge of middle age by. We get older, but they stay the same age. In college football, they are all athletes dying young.

And this is the American dream. Not the metaphorical death—although no country with some of the Roman Republic in its DNA could be free of tendencies toward being a death cult—but the unending youth. The surface-level indications of this are too numerous to name; America loves an image, and no image is stronger than that of the young and beautiful. But it goes down to the roots. Paine can write “we have it in our power to begin the world over again” as if it applies to all of America, but that is fundamentally a young person’s desire. Horace Greeley says, “go West, young man,” and has the decency to specify who should go West. The promise of the frontier is the promise of a place where no one is old.

[I’m so happy that it’s fall and I can stop devoting my Saturdays to lame pursuits, like reading, and resume devoting them to cool pursuits, like watching twelve hours of college football. (Sometimes I read during commercial breaks; usually I change the channel to another game, though.) —Steve]