WRB—Dec. 14, 2022

We went to the WRB Christmas Party and everyone knew you

The Managing Editors are immensely sorry for having missed this Saturday’s issue. Was this tragic? Yes. Avoidable? Probably. Will it happen again? We hope so! [But only once in a blue moon. —Chris]

To do list:

Follow us on Twitter, or Instagram, where Grace, from our recent Children’s Literature Supplement [Issues of which are archived here for ease of access.], has promised to actually post things;

Order a tote bag or now a MUG;

If you would like a set of Finite Jest volumes, now in both hardcover and significantly less expensive paperback [Maybe for Christmas?], use this form;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, now stored on this page for non-paying readers to access, either by placing or responding to one;

and, now for a greatly (40% or so) reduced price for a yearly subscription through the end of the year,

Links:

It’s “How to Be Funny week” at Gawker. Here’s WRB-fave Dan Brooks on Wodehouse: “The image of Wodehouse as some sort of manic literary beaver is one of the singular pleasures of reading his work.”

Department of Centenary Reconsiderations:

For the Boston Review, Johanna Winant writes about 100 years of Ulysses, The Waste Land, and the Tractatus, three books united by a common year of publication and a common interest in being very annoying to read:

It’s not controversial to describe modernist literature as challenging. Wittgenstein admitted to a potential publisher that the Tractatus would appear “strange,” and Eliot wrote that modern art “must be difficult.” Using The Waste Land as a case study, literary scholar Leonard Diepeveen argues in The Difficulties of Modernism (2003) that “the rapid proliferation of difficulty was an immediately noticeable characteristic of modernism, at times even going so far as to claim that difficulty, because of its preponderance, defined modernism.”

But there are many ways to be difficult; George Steiner, in his classic 1978 essay “On Difficulty,” identifies four. The first is contingent difficulty, which can be resolved with more information. These difficulties, Steiner writes, are “the most visible, they stick like burrs to the fabric of the text,” but “theoretically, there is somewhere a lexicon, a concordance, a manual of stars, a florilegium, a pandect of medicine, which will resolve” them. Then there is modal difficulty, whereby “large, sometime radiant, bodies of literature have receded from our present-day grasp” due mainly to the passage of time. Steiner’s third type of difficulty is tactical: when “the poet may choose to be obscure in order to achieve certain specific stylistic effects.” Last, there are ontological difficulties, which “confront us with blank questions about the nature of human speech, about the status of significance, about the necessity and purpose of the construct which we have, with more or less ready consensus, come to perceive as a poem.”

And for Poetry, just on The Waste Land, Ryan Ruby notes, among many other points in a really magnificent essay, that “modernism” is pretty old at 100 years on:

What we are celebrating when we commemorate the centennial of The Waste Land is less the singular achievement of a particular poet than the moment when the aforementioned aesthetic norms improbably broke through to a popular audience and became the idiom in which art was produced, received, discussed, interpreted, judged, and—one wants to say—lived. That is perhaps why it has been difficult not to detect in the many centennials this year an undercurrent of melancholy and nostalgia, a mixture of memory and desire. Since 1989, it has become increasingly clear that the high Modernist period was a historical exception and the current era is the historical rule. Although the time-travel simulation of anniversary rituals allows readers to taste a little of the excitement of reading these works when they were first published, it comes with the uneasy recognition that the culture of the current era doesn’t measure up.

And for The American Scholar, on Matthew Hollis’ book out this week on the same topic [The Upcoming book from Oct. 8, 2022], A.E. Stallings: “Surprisingly suspenseful, Hollis’s book shows how, at many turns, Eliot’s poem could have ended up something else, full of scattered brilliances but not the sustained masterpiece we have today.”

And The Paris Review has the text of a lecture recently delivered by Sally Rooney on Ulysses:

Okay, okay, you might be thinking. James Joyce is the successor of Jane Austen, really? Ulysses is an updated version of the marriage plot? That’s enough misreading for today, thank you. And indeed, past a certain point I do begin to feel like a little girl who has been allowed to play for too long with her brothers’ toys, and is now surreptitiously making the action figures kiss. Ulysses is for girls, I mutter under my breath….Naturally, I lay no claim to objectivity. The Ulysses I present to you this evening might sound suspiciously like a novel about attractive young people in their twenties and thirties hanging around Dublin, doing no work, and thinking about sex; and there may be reasons such a reading appeals particularly to me.

“The atmosphere was captured some years earlier when, on a visit to Lawrence’s house in New Mexico, W.H. Auden recorded: ‘Cars of women pilgrims go up every day to stand reverently there and wonder what it would have been like to sleep with him.’ Suitably, Lady Chatterley outsold the Bible in the year after the trial.” For Unherd, Nicholas Harris on the myth of Lady Chatterley, which is, blessedly, not quite 100.

Speaking of Auden: for Print magazine this week Maria Popova writes about what a bummer it was to be W.H. Auden: “‘The More Loving One’—the second verse of which became the epigraph of Figuring, and which appears in Auden’s indispensable Collected Poems—is a poem both profoundly personal and profoundly universal, radiating a reminder that no matter the heartbreak, no matter the entropic undoing of everything we love and are, we are survivors.” [I mentioned this poem way back in March. —Chris]

More distantly still related to Auden: Lincoln Michel interviews Elisa Gabbert on his Substack about writing Normal Distance (September) [The Upcoming book and Poem from Sept. 10, 2022! —Chris].

One more interview: James Surowiecki interviews Geoff Dyer, whose collection The Last Days of Roger Federer [See Terry Eagleton’s review in WRB July 6, 2022] came out in May, for The Yale Review.

Reviews:

In September we linked to reviews of Jana Prikryl’s new collection of poetry (Midwood, August) and a sequel novel (Heat 2, August) to the film Heat (1995). Here are new entries on both:

Christian Lorentzen for Galerie [I’ve clicked around this site cursorily and don’t really know what it’s deal is. Anyway I guess I’m getting their emails now. —Chris] on Heat 2:

Call it the outlaw sublime—a style that channels the tradition of the American tough guy and re-aestheticizes the hardboiled existentialism of the 1930s and ’40s for the postmodern era. Mann’s romanticism may be retro, but he and his characters move through an ultramodern world of networked security systems, ubiquitous surveillance and globalized capital. There’s a continuity to his historical epics and sleek crime pictures. Whether set among the tangled freeways and glass towers of Chicago, L.A. or Miami; the pre-Revolutionary wilderness; or the hardscrabble streets of Depression-era America, Mann channels the same visual grandeur and parses the same logic of honor. He belongs to the generation that arose in the aftermath of studio Hollywood and the flourishing of the French New Wave.

Babe wake up! There’s a new William Logan roundup in The New Criterion! He’s got it out for Nebraska. But he actually liked Midwood: “I’m drawn to these poems that resist the reader, that wave like lost souls, longing for resolutions never to be reached. Even in a minor mode, Prikryl is one of the strangest and most unclassifiable poets we have.”

Speaking of Nebraska, last month we linked to an excerpt from Jon Lauck’s new book on the history of the Midwest (The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800–1900, November).

Mark Athitakis reviews it for the local Post: “A template for fairness in education, voting rights and community in America was in large part set in the Midwest. In the main, it was a ‘culture of democratic advancements, open politics, literacy and learning, economic self-determination, and ordered freedom,’ Lauck writes.”

And Hendrik Meijer reviews it in National Review: “Some of us in the Midwest suffer from region envy. How richly identifiable is flinty and literate New England, the South in all its gothic glory, Texas because it is Texas, and the vibe that belongs to California. Are we resigned to the ranks of the nice but nondescript? Lauck, a Dakotan and preeminent midwestern historian, knows better. For him the Midwest—broadly the Great Lakes states extending through the Great Plains—has its own compelling singularity.”

Speaking of last month, we linked to Mick Herron’s essay on John le Carré in the TLS. Here’s Sam Adler-Bell’s review of John le Carré’s recently-issued letters “compiled, edited, and annotated by le Carré’s son Tim Cornwell” (A Private Spy, December) [Previously mentioned here.] in The Baffler:

Le Carré was fond of Auden’s line, “Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return.” And so it goes, he thought, for nations as well as families. (Of course, it is far easier to harmonize these registers—the intimate and the geostrategic—in the novel than in political reality; this is perhaps why le Carré’s own political compass could be erratic at times.) “The winners forget, but the victims have terribly long memories,” he wrote in a 2009 letter to August Hanning, then Germany’s domestic security chief, “and we have paid for that, & will pay for it—just as in Ireland.” Terrorism, le Carré held, was a return of the repressed, no less wicked for being explicable. And he saw the war on terror as a neurotic effort to reclaim and redeem Western moral vigor. George W. Bush, in his desire for war with Saddam Hussein, personalized the dynamic: a son seeking to win his father’s war. “If anybody had killed my Daddy, or even tried to,” le Carré quipped in a letter, “I’d have given him my favourite conker.” In le Carré’s world, misery and memory were locked in mad, morbid embrace.

[I just want to say, the notion of “reviewing” a collection of letters is deeply amusing to me. Imagine reviewing someone’s texts. —Chris]

And Michael Press reviews a big slate of books on Egyptological themes for the TLS. We don’t recall having ever linked to a topic like this before.

Speaking of topics we haven’t linked to before, in the LRB Laleh Khalili reviews a recent book by Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe about the consulting firm McKinsey (When McKinsey Comes to Town, October): “One gets the sense that Bogdanich and Forsythe think the consultants they write about are rotten apples, but the barrel is sound. Their own material makes clear, however, that all the services often spoken of as merely helping businesses and government departments run more efficiently—management consulting, audit, software development—are in fact focused on enabling capitalists to enrich themselves further without the inconvenient interference of workers, taxpayers or regulation.”

N.B.:

“Here Robin Whitten, AudioFile’s founder and editor, picks out five outstanding audiobooks in a range of genres and explains what it is that makes them special.”

Post45 Data Collective has a table of “the winners and judges of prizes for prose, poetry, or unspecified genre between 1918 and 2020 with a purse of $10,000 and over.”

Carpe Librum has opened a pop-up bookstore at 1350 I Street NW through the end of January. “Books, CDs, DVDs, and vinyl are on sale for $6 and under.”

There’s a new issue of The Lamp coming soon, and a new issue of Socrates on the Beach already here.

“A madeleine-flavored macaron?” But Why?

Upcoming book:

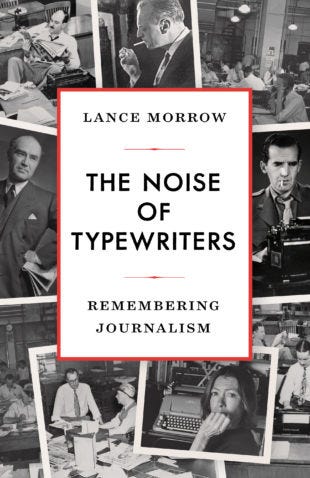

January 24 | Encounter Books

The Noise of Typewriters: Remembering Journalism

by Lance Morrow

From the publisher: W.H. Auden wrote, “Poetry makes nothing happen.” Journalism is a different matter. In a brilliant study that is, in part, a memoir of his 40 years as an essayist and critic at Time magazine, Lance Morrow returns to the age of typewriters and to the twentieth century’s extraordinary cast of characters—statesmen and dictators, saints and heroes, liars and monsters, and the reporters, editors, and publishers who interpreted their deeds. He shows how journalism has touched the history of the last 100 years, has shaped it, distorted it, and sometimes proved decisive in its outcomes.

The Noise of Typewriters is, among other things, an intensely personal study of an age that has all but vanished. Morrow is the son of two journalists who got their start covering Roosevelt and Truman. When Morrow and Carl Bernstein were young, they worked together as dictation typists at the Washington Star (a newspaper now extinct). Here is a striking profile of Henry Luce, Time’s founder, whom Morrow considers the most consequential journalist of the twentieth century. Morrow remembers Dorothy Thompson, Joseph and Stewart Alsop, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Otto Friedrich, Michael Herr, and other notable figures in a golden age of print journalism that ended with the coming of television, computers, and social media. The Noise of Typewriters is the vivid portrait of an era.