WRB—Dec. 9, 2023

“Reading print magazines”

She subscribed to the Washington Review of Books. Skipping nothing, she devoured all the reports of first nights, horse races, and soirées, took an interest in the debut of a singer, the opening of a shop. She knew the latest fashions, the addresses of the good tailors, the days for going to the Bois and the Opéra.

Links:

Two from The New Yorker:

A profile of Christian Wiman by Casey Cep:

Part of what Wiman was doing in those days was looking for a form, not only for his art but also for his experiences of existential arrest and excess. Having left the Church, he tried to find meaning in literature, kicking the tires of aesthetic theories like those of Matthew Arnold and Wallace Stevens, test-driving the possibility that poetry could fill the void left by religion. But his poems, when they were good, seemed to come not from his conscious mind, exactly, but from some perfect sound he felt as if he had overheard, some indeterminably inward or outward voice, which he did everything he could to capture. In another essay, written before his return to Christianity, he explains, “There are even moments, always when writing a poem, always when I am suspended between what feels like real imaginative rapture and being absolutely lost, that I experience something akin to faith, though I have no idea what that faith is for.”

[The Poem in WRB—Apr. 23, 2022 was a translation by Wiman of a poem by Osip Mandelstam, and his most recent book, Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries against Despair (December 5), was the Upcoming book in WRB—Nov. 18, 2023, in which we also linked to an excerpt from it.]

Parul Sehgal on the lives of critics [Critics have lives? —Steve]:

It’s a pity that so many showed the same signs of the unfortunate orientation at a young age. In fact, a Max Jamison composite comes together rather neatly. Here’s roughly what we’re dealing with: A family that’s marginalized in some way. A child, inculcated early in holding herself apart, perhaps nurturing some deeply held feelings of difference, even freakishness, develops a taste for blissful alienation, confirmed by engulfment in art. (Food critics attest to precocious appetite in a more literal fashion. Raymond Sokolov, in the memoir Steal the Menu, reports that, as an infant, he drank three bottles at every feeding.) Education is likely to be spotty and marked by cheerful hostility to received opinion. Elizabeth Hardwick sat incredulous at exam time, watching her classmates diligently scribbling—she was supposed to tell the professors what she knew they already knew?

In Longreads, Harrison Scott Key tells the story of his saddest Christmas, which he “spent guarding $100,000 worth of explosives on the surface of the moon”:

“Your momma’s worried, son. The machete will make her feel better. I sharpened it,” he said, thumbing the blade.

Pop had brought along my old 12-gauge pump, my .30-.06 rifle, and three preloaded clips with 220-grain shot, in case the fireworks tent was attacked by a team of bison.

“And some pistols,” he said, handing me a bag of pistols.

“Thanks, Pop,” I said, transferring the arsenal to my trunk, a few parking spaces over.

Sometimes, when I think about my life, I think about the quiet moments that may have shaped me more than I could’ve known, like the time my father handed me a sack of guns in a dormitory parking lot because he didn’t want me to die.

In the new issue of The Lamp, Nathan Payne on Clifton Fadiman’s approach to the task of popularizing the Great Books:

In The Lifetime Reading Plan, Fadiman avoids some of the mistakes that mar the Great Books set. For one thing, he takes a humbler approach to his selection of books. In his introduction, titled “A Preliminary Talk with the Reader,” he tells us that the Lifetime Reading Plan is “not in any absolute sense a list of the ‘best books’” and that “no single scholar” would find it “satisfactory in all respects.” Fadiman is at such great pains to insist that his guide is no substitute for a formal education, and that he cannot make any sure claims for it (“It will not make you happy—such claims are advanced by the manufacturers of toothpastes, motorcars, and deodorants, not by Plato, Dickens, and Hemingway”) that it almost seems like he anticipates the critiques of the likes of Macdonald, and crafts his rhetoric so as to neutralize them in advance.

In The New Statesman, Julian Barnes on the inescapable influence of the family on writers, no matter what they do [My own father, Philip Larkin, wrote a rather famous poem about this. And it puts a whole new spin on “Maman died today.” —Steve]:

But some kind of revolt is inevitable, because the vestigial writer or artist is seeking to express his or her individualistic vision of the world, which inevitably conflicts with that of the parent. A father doesn’t have to be tyrannical, or a mother over-protective, for them to want things to stay the same, and for the child not to grow up—or not in such a way that he or she becomes a writer. A poet friend of mine had a money-man father who was puzzled by his choice of “career.” “The thing is, son, you’ve got to have something to aim for. What are you aiming for?” “Nobel Prize, Dad,” replied my friend, an answer which was strangely judged satisfactory.

In The Critic, Michael Duggan on the interwar travel writing of Patrick Leigh Fermor and the lost Europe it depicts:

The great severing of Europe, in time and space, hit Patrick Leigh Fermor personally. In 1935, in Athens, he met and fell in love with Balasha Cantacuzène, sixteen years his elder, a princess and painter belonging to one of the great dynasties of eastern Europe. They spent much of their four years together on the run-down family estate in Moldavia, Rumania, from whence Paddy returned to England immediately after Britain declared war on Germany in order to sign up. He later wrote an account of the last day of peace in Moldavia when he rode with others in a cavalcade of horses and an old open carriage, through sunlit fields and vineyards, to a mushroom wood. Coming home, “The track followed the crest of a high ridge with the dales of Moldavia flowing away on either hand. We were moving through illimitable sweeps of still air.”

Reviews:

In our sister publication across the pond, Erin Maglaque reviews a book on “the bibliophile’s bibliophile” (Aldus Manutius: The Invention of the Publisher by Oren Margolis, December 5):

He was so busy that he hung a sign on his door: “Whoever you are,” he warned, “Aldus insists on asking you to state whatever you want from him as briefly as possible, and then immediately to leave.” There was one exception. “Unless, that is, you have come, like Hercules, when Atlas was exhausted, to shoulder the load.” Everywhere he looked was work and more work: corrupted manuscripts, fragments; nothing was complete, nothing was fully preserved. He was cleaning away the accumulated errors of centuries; he compared editions, sought out the best manuscripts. As an editor, Aldus said he had to “assume [the author’s] mindset,” and perform a philological ventriloquism. When presented with a worm-eaten manuscript: what would Euripides have written? To rescue every single work of antiquity from obscurity: the scale of the work was endless, self-obliterating.

[No information on his preferences in cover design, alas. —Steve]

In our sister publication in the Forest City, Zack Schlosberg reviews a novel by Fanny Howe, written in the 1990s but published last year (London-rose, 2022):

By denying sex its ordinary locus in human relation, the celibate drives sex inward, into her own being and her senses that open to experience. “Celibacy,” the narrator of London-rose announces, “is not cerebral but blushes like a salamander and intensifies all colors.” Celibacy, that is, does not depend upon another for provision, but calls forth otherness—knowledge—from deep within, the way a salamander changes color according to its shifting sense of the physical world. Change comes not from the outside but from a strong and pending reserve of interiority. The question for Howe, and her narrator in London-rose, is how to shift one’s dark interior into something like light.

N.B.:

New Directions is having a holiday sale.

Apparently “TikTok made cottage cheese cool.” [Cottage cheese has always been cool, and you have been too sinful to see it. It was not something we ever had in the house growing up, and so it continues to have a kind of forbidden allure to me. I realize I am the only person who thinks this. —Steve]

An idea for a Substack dating app. [In the end, every app is a dating app. —Steve]

An explanation of the Gävle Goat, which is forty feet tall, made of straw, and the target of attempts to burn it down every year. (h/t it's only dark)

New issue of The Lamp, as linked to above.

Poem:

“Four” by Chad Walsh

The massacre of solar hydrogen

To warm our blood is a mad, spendthrift thing.

In a system planned by provident men

Summer would be a lengthened name for spring;

The old wastrel, that sun, he would be rationed

In his consumption of his vital core

So a few extra centuries of us could be stationed

On the earth to shiver a few centuries more.Still, sitting out here with you in the patio,

Naked as the neighbors up the hill will permit,

Inwardly, outwardly, dually aglow,

I’ll let him squander the patrimony a bit

Of my blood claimants in the n + n degree.

I’ll never see them, and they’ll never see me.

[This is from Walsh’s 1954 Twenty-Three Sonnets: Eros and Agape. (Also from Heartland. Also out of print.) Walsh was, among other things, a C. S. Lewis scholar and co-founder of the Beloit Poetry Journal.

It was the phrase massacre of solar hydrogen / to warm our blood that first struck me about this poem, but the phrase that ends up seeming the most crucial by the end of the poem is mad, spendthrift thing. There’s a tension throughout the poem between extravagance and a more restrained responsibility: in a system planned by provident men, there would be rationing of the sun’s power to ensure that the life of the world would be extended, albeit in a colder form. Instead, Walsh shows, there’s a recklessness to the mad, spendthrift world as it is.

In the octet, this tension plays out on the level of creation, but in the sestet it plays out within the context of the romantic relationship between the speaker and the addressee. The two of them sit naked as the neighbors up the hill will permit, having pushed the bounds of responsibility to their neighbors as far as they can, all while soaking up the sun, unbothered by their supposed recklessness or how it will affect their blood claimants down the line. In that way, this is a poem that operates deeply in the mode of eros: mad and spendthrift, the lovers declare their allegiance only to the present moment, together in the sun. —Julia]

New book:

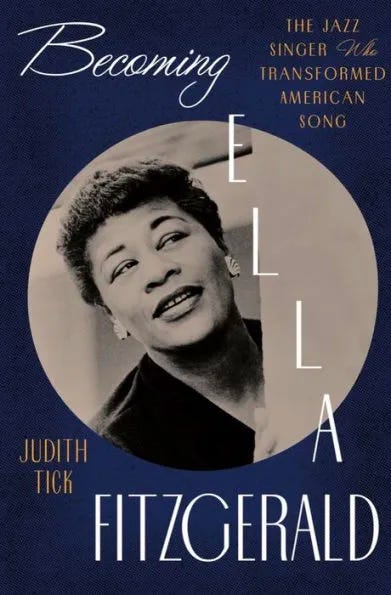

Norton | December 5

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song

by Judith Tick

From the publisher: Becoming Ella Fitzgerald clears up long-enduring mysteries. Archival research and in-depth family interviews shed new light on the singer’s difficult childhood in Yonkers, New York, the tragic death of her mother, and the year she spent in a girls’ reformatory school—where she sang in its renowned choir and dreamed of being a dancer. Rarely seen profiles from the Black press offer precious glimpses of Fitzgerald’s tense experiences of racial discrimination and her struggles with constricting models of Black and white femininity at midcentury.

Tick’s compelling narrative depicts Fitzgerald’s complicated career in fresh and original detail, upending the traditional view that segregates vocal jazz from the genre’s mainstream. As she navigated the shifting tides between jazz and pop, she used her originality to pioneer modernist vocal jazz. Interpreting long-lost setlists, reviews from both white and Black newspapers, and newly released footage and recordings, the book explores how Ella’s transcendence as an improviser produced onstage performances every bit as significant as her historic recorded oeuvre.