WRB—Feb. 10, 2024

“resistance to sublimate”

That is why, whatever force there may be in my reasonings, seeing they belong to criticism, I cannot hope that they will have much effect on the minds of men, unless you extend to them your protection. But the estimation in which your newsletter is universally held is so great, and the name of Washington Review of Books carries with it so much authority, that, next to the Sacred Councils, never has such deference been paid to the judgment of any Body, not only in what concerns literature, but also in what regards human philosophy as well: everyone indeed believes that it is not possible to discover elsewhere more perspicacity and solidity, or more integrity and wisdom in pronouncing judgment.

Links:

Two in Granta:

Sheila Heti interviews Phyllis Rose about her Parallel Lives (1983) and marriage in general:

Heti: Part of the real power of your book is the sense we get of a writer sublimating writing and thinking about her own marriage into writing and thinking about the marriages of others. Now we are awash in women writing directly about their own lives, a mode which can become a little flat. Do you think something is lost in the contemporary resistance to sublimate—to think about our own lives through thinking about other lives? This came up for me as I was concluding the first draft of my introduction: that there is something to learn in your book about the depth we can get to when we write about our own life through the lens of other lives, as opposed to writing about our own lives directly.

Rose: Thank you. That’s very generous. But I would like to turn the question back, rhetorically, to the author of those wonderful books, How Should a Person Be? (2012) and Motherhood (2018). Don’t you think that all literature involves sublimation of some sort or other? What you bring to a book from your own life does not make or break it. What matters is your art—sentence after sentence, paragraph after paragraph, chapter after chapter. Terms like auto-fiction may stir up interest in critics and readers, but writers will write what suits their talents and needs of the moment regardless. Proust was writing auto-fiction. Thank goodness he didn’t wait for the term to be invented. I personally don’t care where the material for a book comes from, so long as I enjoy the experience of reading it.

James Scudamore on attempting to ghostwrite the memoirs of Stephen James Joyce, grandson of James Joyce:

He told me how much his grandfather had liked a wine from the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel, and that “following his example,” he and Solange had got into the habit of importing it.

“What I really like is a white Burgundy,” he said. “The problem is, I like the white, but the white doesn’t like me.”

I mentioned the scene in Ulysses where Bloom orders the glass of Burgundy and the gorgonzola sandwich.

“Well, if I’d have been him, with a gorgonzola sandwich, I’d have had a red.”

I said I couldn’t remember if it was specified in the book or not.

“Check it.” The glare blazed for a moment, then he relaxed. “Of course, Ulysses is not my favorite book. And that’s where all Joyceans go wrong.” He noticed a dog under a nearby table, and brightened. “Oh! Il y a un cousin par terre! We’ve had one dog in our lives. A long time ago. And we never wanted another one because we had that dog, and that dog was special. We used to ship her back and forth from Africa as excess baggage.”

In The New Atlantis, John Last on the return of bears specifically and wilderness generally to portions of Italy from which they have long been absent:

Throughout the long history of wilderness as a concept in Europe, one quality has perhaps been the most enduring and essential: fear. For the ancients, wilderness was a place of supernatural beasts and evil portents; for medieval Europeans, a dangerous frontier inhabited by unknown perils and temptations. When the Italian Baroque painter Salvator Rosa tried to revive an appreciation of rugged nature, it was the sensation of terribilità he tried to evoke—a sublime sense of power, beauty, and danger.

Today’s Europeans are perhaps well primed to feel this fear again as the ancients did. Robert Hearn notes that as Europeans’ encounters with wild animals have become less common, “a certain childishness” has crept into their relationship with nature—a naïve love of animals coupled with a petulant demand for control. But as many Italians are rapidly learning, wild animals are not saintly sidekicks and cheeky bandits, and neither are they sacred creatures possessed of the kind of individual dignity that makes their death in every case a crime.

[Bears are weird animals. Maybe the most human of all animals. You can’t get into the heads of most of them, but you can get into the head of a bear.—Steve]

In Comment, Jack Bell on the kingfisher and the relationship between human beings and the rest of the world:

The story of Ceyx and Alcyone is an etiology, a narrative that explains how a creature comes to be the kind of thing that it is. In Ovid’s retelling, the narrative discloses the origin of the kingfisher’s fondness for water, its mating and nesting habits, its rattling, doleful call. By reading Ovid’s myth, we come to an understanding of how the kingfisher came to be. But there is another strategy at work too. As we read about a queen who shares a name with the alcyone, the kingfisher, it is difficult not to feel drawn into a strange kinship with the animal that the suffering lover, Alcyone, becomes at the end of the story.

In the Hudson Review, Robert Crossley on speech in Hamlet, especially from the unheard Ophelia:

By contrast, Ophelia is often left speechless or is actively silenced. At the close of the first scene in which she appears—when first her brother and then her father disparage and rule out any love affair with Hamlet—Polonius commands her to keep silence. And she does. Later, after she is made to participate in Polonius’ fantasy by returning Hamlet’s gifts and letters, she approaches her father in a state of distress over the misogynistic invective of Hamlet’s “to a nunn’ry” rants. All she gets is a “How now, Ophelia?,” and she is dismissed without being allowed to say anything. That silencing is followed by her mortification during the play-within-the-play when she is muted by Hamlet’s sardonic compliments and crude insults. By the time Gertrude refuses speech with Ophelia, a strong pattern has emerged. And the gentleman who has been interceding to persuade Gertrude to meet with Ophelia makes the pattern complete. “Her speech is nothing,” he says of Ophelia’s incomprehensible ravings about murder and abandonment. He means that her speech makes no sense, but he also underscores the value that others have placed on Ophelia’s voice: precisely, none.

Reviews:

Two in Bookforum:

Celeste Marcus reviews Rachel Connolly’s recent novel (Lazy City, 2023) [One of the Upcoming books in WRB—Sept. 30, 2023.]:

Refusing to participate in the culture of self-help, and of therapy-speak in particular, is a method of ignoring rather than treating the aftereffects of catastrophe. But that language can be a tool for escapism, too. Readers are denied the comfort of fleeing Erin’s heavy monologue and finding refuge in the vernacular we invoke to explain trauma and the traumatized to ourselves. This vernacular is useful, of course, but it comes with a price. Connolly’s refusal to use this language shields her from reducing Erin and her ilk to clinical typologies. Erin bristles at being cast as another victim in the cultural imagination. She demands recognition—from herself and from us. Several times she stares at herself in the mirror and smiles. This ritual is the soul of the novel: Erin is looking for herself. She is rigorously seeking the version of herself that isn’t a simulacrum of the girls she sees at the bar or reads about in magazines. She’ll find what she’s looking for by reckoning with the cataclysm that forced her from her former self.

Katie Kadue reviews Lars Iyer’s recent campus novel (My Weil, 2023):

The conceit is a familiar one to anyone who has spent time in an academic humanities department: the practice of turning assignments in on time requires a different understanding of time than, for example, the theory of messianic time developed by Walter Benjamin. Graduate students like to make jokes based on such mismatches of theory and practice. How can we possibly complete essays on the poetics of incompletion? How can we possibly work on our thesis on antiwork politics? These one-liners can pass the time in the library or on social media. When cannily deployed, they might even invite us to think seriously about the contradictions that structure our lives. But they become tiresome when unrelentingly repeated over the course of multiple heavily italicized pages of a novel.

In our sister publication in the Forest City, R. K. Hegelman reviews a translation of Rilke’s lone novel (The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, 1910, translated by Edward Snow, 2022):

As Malte will eventually deem, “I prayed for my childhood, and it has returned, and I feel that it is just as difficult now as it was then, and that growing older has done me no good at all.” He proceeds to only venture further back in time in search of an unsullied purity, hence the several impromptu fictions that hark back to the medieval, and the consistently gothic flavor to his anecdotes, whose anti-modernity stems not from the likes of a Pre-Raphaelite romanticism but the morbid reality of the times, “the heavy, massive enmity of that era.” The tale of a hunting party, led by the court jester, recovering the mutilated body of the Duc de Lorraine; the queer insanity of Charles VI of France—the pervasiveness of death in all of these visions brings him no nearer to a reconciliation with it.

In the Journal, Meghan Cox Gurdon reviews a book about the love letters of the presidents (Are You Prepared for the Storm of Love Making?: Letters of Love and Lust from the White House, by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, February 6):

By contrast, there’s a gap between the ruthless Richard Nixon conjured in the public imagination and the vulnerable young beau who wrote of himself as if he were a character in a story in a letter to Pat Ryan in (probably) 1938: “Though he is a prosaic person, his heart was filled with that grand poetic music, which makes us wish for those we love the realization of great dreams, the fulfillment of all they desire.” To Jacqueline Bouvier, John Kennedy wrote “almost nothing,” the Hooblers observe, before or after their marriage; nor it seems has Barack Obama done much letter writing to Michelle. The Hooblers regret the paucity of letters between the Obamas, a textual failure that denies posterity access, they say with a touch of mawkishness, to “words that passed between them that might give an insight into two of the most interesting people of our time.”

[I like the letter from a young John Adams to Abigail before they were married in which he jokingly catalogs her faults, among which are:

You do not sit, erected as you ought, by which Means, it happens that you appear too short for a Beauty, and the Company looses the sweet smiles of that Countenance and the bright sparkles of those Eyes.—This Fault is the Effect and Consequence of another, still more inexcusable in a Lady. I mean an Habit of Reading, Writing and Thinking. But both the Cause and the Effect ought to be repented and amended as soon as possible.

I also like the letter from a middle-aged John Adams to Abigail, his wife of two decades, in which he informs her “if I am cold in the night, and an additional quantity of Bed Cloaths will not answer the purpose of warming me, I will take a Virgin to bed with me.” He then adds “Ay a Virgin.—What? oh Awful!” before explaining that a “virgin” is a kind of hot water bottle used to keep beds warm. —Steve]

N.B.:

“The Glitzy IRL Book Party Is Back, Baby” [I’m happy for New York City. —Steve]

Companies are moving back to ads and away from subscriptions. [The Washington Review of Books advertises the genius, sophistication, learning, and taste of the Managing Editors. —Steve]

Standard Industries is in talks to buy Air Mail.

An interview with Tony Stubblebine, CEO of Medium.

A New Zealander on Americanizing novels written in the non-America Anglosphere. [Paging my favorite Canadian Tory. —Steve]

Belt Publishing has been acquired by Arcadia Publishing.

Capitol Hill Books is hiring.

New issues:

Granta 166: Generations [As linked to above. I love the Nico Walker short story in here. —Steve]

Hudson Review Winter 2024: Volume LXXVI, No. 44 [As linked to above.]

The New Atlantis No. 75—Winter 2024 [As linked to above.]

Bookforum Winter 2024 [As linked to above.]

The Dial Issue 13: Order

Image is shutting down. R.I.P.

Seiji Ozawa died on Tuesday, February 6. R.I.P.

Mojo Nixon died on Wednesday, February 7. R.I.P.

Local:

An exhibit of German Expressionism and later artists influenced by it opens at the National Gallery of Art tomorrow, February 11.

Poem:

“How the City was Founded” by Campbell McGrath

She feels the sting of a burr in her heel

and sets her basket down just there,

where the stream widens coming down from the hills,

and sits on a log by the water.Shafts of sunlight animate broad shoals

of river gravel, clumped mussels

beard the rocks and the clear green shallows

are full of lazy fish. Pretty and useless,her daughter stands beside her. “Sweetheart,”

she says, “run and tell your father

to move the camp over here. My feet hurt

and I’m not walking any farther.”

[This poem is from the Summer 2023 issue of 32 Poems. —Julia]

Upcoming books:

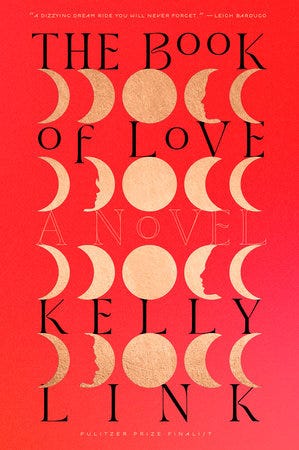

February 13 | Random House

The Book of Love

by Kelly Link

From the Lit Hub preview: It’s not so often that a debut novelist is already a MacArthur “Genius” Grant recipient and a Pulitzer finalist, but then we’ve been waiting for Kelly Link’s debut novel for a long time now. Lovers of big, immersive literary fantasy (and, of course, of Link) will not be disappointed—this is a nimble, clever, and deeply satisfying novel, in which a handful of teenagers, most of them recently dead, get dragged into an age-old grudge match between mythic creatures of unending (or possibly ending, but no spoilers) power. All of it is rendered in Link’s trademark winking, personable prose, which tends to deliver something pleasurable on every page. (Very often, in this case, it is a sassy comeback.) So yes, this novel has Big Buffy Energy—that is, sometimes it is fun and ridiculous, sometimes it is a tragedy on an epic scale, but always there is someone looking askance at the goings-on, even while their world is ending. Well, there are worse ways to get through February.

Also out Tuesday:

Other Press: The Age of Magic by Ben Okri

From the publisher: Eight weary filmmakers, traveling from Paris to Basel, arrive at a small Swiss hotel on the shores of a luminous lake. Above them, strewn with lights that twinkle in the darkness, looms the towering Rigi mountain. Over the course of three days and two nights, the travelers will find themselves drawn into the mystery of the mountain reflected in the lake. One by one, they will be disturbed, enlightened, and transformed, each in a different way. An intoxicating and dreamlike tale unfolds. Allow yourself to be transformed. Having shown a different way of seeing the world, Ben Okri now offers a different way of reading.

What we’re reading:

Steve read more of Stanley Fish’s How Milton Works (2001). [At this rate I’m going to finish it by May. The portion I most recently read featured a comparison of the meeting of the Lady and the titular character in Comus to the meeting of Venus and Aeneas in Book 1 of the Aeneid. It also featured Fish taking to task those who forget that Milton excludes Catholics and some others from the toleration he advocates in the Areopagitica, which is very important to understanding that text. Wonderful stuff. —Steve] A friend gave him a copy of Far from the Madding Crowd so he’s going to start that soon. [Year of Thomas Hardy? —Steve]

Julia has been reading Colette’s Chéri (1920) and just started Robert Cording’s In the Unwalled City (2022).

Critical notes:

Dirt asked a bunch of people “is it better to desire or be desired?”

The WRB Slack responds:

[Yes. —Steve]

[This is a circular question because you’re burying “do you [desire to] desire or [desire to] be desired.” —Chris]

[I agree with Chris . . . and besides it being a circular question, it’s a dishonest one. To truly desire someone encompasses wanting them in their entirety, which necessarily includes desiring their desire . . . it’s impossible to honestly prefer one as “better,” because they are intrinsic. Anything less is just longing or yearning, which are desire lite, for cowards and children. —Hannah]

[I have never experienced either of these things and have no plans to do so any time soon. I just read poems. —Julia]

[The Almighty and Ever-loving God desires us all infinitely and individually. Therefore, human adulation cannot truly add to the amount any given soul is “desired.” Thus, the only real human activity is setting about to desire God, that is to say, the source of all Good, over and above all earthly things. Can you tell I grew up on the Baltimore Catechism? —Grace]

[Fuck you. —Jude]

Those two selves were also profoundly entangled. In many ways, Marian Lewes’s relationship provided her with the conditions that enabled George Eliot’s writing. From the outset, Eliot’s work was a shared endeavor with her partner: Lewes submitted the books to editors on her behalf, negotiated her contracts, and held distractions at bay. Not only did her relationship provide subject matter for her marriage plots, but the complexity of her domestic arrangements also gave her the requisite distance to think critically about the institution, which resulted in her searing indictments of marriages based on illusions or made for imagined gain. Maintaining so many competing identities—and preserving the secret of her authorship—posed a serious ongoing challenge to Eliot’s sense of self. Becoming Mrs. Lewes, Carlisle writes, was not “an easy lapse into social conformity, but a precarious balancing act—and people were watching to see if she would fall.”

Henry Oliver on Iris Murdoch [A bit of an expansion of his writing on Murdoch we linked to on Wednesday.]:

It is often said that love is her subject, but that isn’t quite right. Murdoch is a novelist of the good. Inspired by her hero Plato—and his philosophy that Eros can lead us to goodness through an appreciation of beauty, and of the beauty within the people we love—Murdoch designed her novels, even the entertaining capers, to show us that the surface of life is a trap: lust, ego, ambition, greed, selfishness all capture us and make us prey to what she called the “fat unrelenting ego”.

What really matters, Murdoch is constantly saying, is the “otherness of the other person”. We must get outside ourselves; go through the difficult, wrenching realization of what it really means for other people to exist. The fantasy lives in our head are morally dangerous, Murdoch warns. We must get out into the world, to other people.

From an 18th century defense of Bach by Johann Abraham Birnbaum:

The last exception the author wishes to take to the pieces by the Hon. Court Composer amounts to this: that “all the voices work with each other and are of equal difficulty, and none of them can be recognized as the principal voice” (by which presumably the upper voice is meant). Now, the idea that the melody must always be in the upper voice and that the constant collaboration of the other voices is a fault is one for which I have been able to find no sufficient grounds. Rather, is it the exact opposite that flows from the very nature of music. For music consists of harmony, and harmony becomes far more complete if all the voices collaborate to form it. Accordingly this is not a failing but rather a musical perfection, and I am very much astonished that the author could consider this a failing, since it is characteristic of the Italian taste, nowadays everywhere so highly admired, especially in church works. The author need only look into the works of Praenestinus [Palestrina], among the old composers, or [Antonio] Lotti and others among the more modern ones, and he will find not only that all the voices are continuously at work but also that each one has a melody of its own that harmonizes quite well with the others.