WRB—Feb. 22, 2023

“It wasn’t the most literary conversation I had in Washington, but it was close.”

Don’t Shoot the Managing Editor; He’s Doing the Best He Can

[This is going to be a quick one today. —Chris]

To do list:

order a tote bag or now a MUG;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, either by placing or responding to one;

and,

Links:

Sam Leith on the Roald Dahl news event in The Spectator:

This panic is old wine in new bottles, and we should try to look at it coolly. You make a weak case, I think, if you insist that you “vandalize” Dahl’s books beyond recognition by the snipping of the odd phrase here or there. Some poetry is that vulnerable; relatively little prose is. These stories aren’t sacred texts, and you do them no favors by fetishising them as if they were. Stories are robust things. Is giving up a little of the books’ distinctiveness a price worth paying to try to help create a culture where overweight children aren’t bullied in the playground? That’s the calculation that the publishers have made, and it isn’t one to be dismissed out of hand. Fine-sounding principles about the inviolable sanctity of Art are no comfort to an eight-year-old in tears.

Edmund Racher on mid-century fiction and the decline of Rome in Antigone.

In The Hedgehog Review, Alan Jacobs on [Forgotten, of course,] novelist Hope Mirrlees, “a satellite member of the Bloomsbury group” whose Paris (1920) “Virginia Woolf thought ‘obscure, indecent and brilliant.’”:

Like many other fantasy writers, Mirrlees is interested in what happens if the power of Fairyland cannot be wholly excluded from our well-buffered society. In this case, we see what happens when magic begins to creep back into well-ordered and well-buffered lives. To figure this as essentially a drug war—an inevitably unsuccessful attempt to prevent the smuggling of what one character in the story significantly calls the “commodity” of fairy fruit—is a wonderful conceit and developed with delightful panache, tracing an elegantly oscillating line between the economic and the metaphysical. When one character tells a senator that he should be more aware of the high levels of consumption of fairy fruit among the poor, I find myself murmuring, Fairy fruit is the opiate of the masses.

Christian Lorentzen reporting in Harper’s on last year’s local publishing antitrust hearings:

“My name is Stephen King. I’m a freelance writer,” the seventy-five-year-old novelist said, as though he were at an AA meeting that happened to be populated mostly by lawyers rather than by alcoholics (or freelance writers). The story of King’s publishing history is a fascinating one, as such stories go. He published Carrie with Doubleday in 1974, with no agent, and received an advance of $2,500. He received no royalties from the film adaptation, but “Signet published a movie tie-in edition and that did very well.” After five books with Doubleday, all of which received low advances but turned out to be bestsellers, King accepted the representation of Kirby McCauley, an agent for “a lot of old-time horror and fantasy writers,” whom he’d bumped into at a party for the romance writer Helen Van Slyke. McCauley convinced him to go to Doubleday with an offer of three books and an ask of $2 million. “And the man who’s negotiating on Doubleday’s behalf,” King said, “a man named Robert Banker, laughed and walked out of the restaurant.”

N.B.:

[I like how subtle most of these are. Pleasing. —Chris]

Pulitzer Prize: “The 2014 general nonfiction winner, Tom’s River by Dan Fagin, went from 10 copies [before the prize announcement] to 162 copies sold (6,266 copies sold to date) on BookScan [which measures a significant proportion of industry sales].”

RIP Michael Deville: Le cinéaste Michel Deville est mort.

“The Most Disastrous Decision in Corporate Publishing History”

Issues:

New issue of Orion: “The Language of Nature: Translation and the words that define our world”

March issue of Harper’s.

Local:

Tonight through Subday: Balanchine! | Kennedy Center

Book (Washington Drawings: Abe to Zoo, 2022) review in The American Conservative:

As you would expect from a world-class civic planner, Thadani offers several detailed maps of D.C.’s streets, buildings, and quadrants. “Q,” Quadrants, notes that the areas Northeast, Northwest, Southeast, and Southwest derive their ordinal directions from a medallion in the crypt beneath the Capitol’s Rotunda. “D,” Dumbarton Oaks, reproduces each lawn, path, and hedge of Washingtonians’ favorite pleasure garden. And you will find two period drawings of Thadani’s predecessor, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, designer of Washington, the District of Columbia, and with these drawings, notes on the particulars of designing a city suited to citizens at Liberty.

“‘This is an organized society, this is how these things work. We have rules and laws for a reason,’ says Erin, who used to be an administrator for an Eckington Buy Nothing group.” Love this stuff.

Upcoming book:

March 7 | Columbia University Press

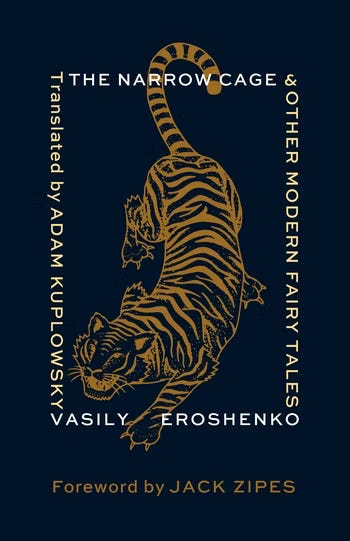

The Narrow Cage and Other Modern Fairy Tales

by Vasily Eroshenko, translated by Adam Kuplowsky

From the publisher: Vasily Eroshenko was one of the most remarkable transnational literary figures of the early twentieth century: a blind multilingual Esperantist from Ukraine who joined left-wing circles in Japan and befriended the famous modernist writer Lu Xun in China. Born in a small Ukrainian village in imperial Russia, he was blinded at a young age by complications from measles. Seeking to escape the limitations imposed on the blind, Eroshenko became a globe-trotting storyteller. He was well known in Japan and China as a social activist and a popular writer of political fairy tales that drew comparisons to Hans Christian Andersen and Oscar Wilde.

The Narrow Cage and Other Modern Fairy Tales presents a selection of Eroshenko’s stories, translated from Japanese and Esperanto, to English readers for the first time. These fables tell the stories of a religiously disillusioned fish, a jealous paper lantern, a scholarly young mouse, a captive tiger who seeks to liberate his fellow animals, and many more. They are at once inventive and politically charged experiments with the fairy tale genre and charming, lyrical stories that will captivate readers as much today as they did during Eroshenko’s lifetime. In addition to eighteen fairy tales, the book includes semiautobiographical writings and prose poems that vividly evoke Eroshenko’s life and world.