The movement of the Washington Review of Books, on the contrary, is patently from despair through a series of insights to triumphant joy.

N.B.:

[Nic1 and I started the WRB two years ago this week with the mission: “Our goal is fundamentally to deliver a bulletin that is a quick and enjoyable way for you to hear about good and interesting writing and good and interesting books.” —Chris] [Now our goal is fundamentally to deliver a bulletin that is a quick and enjoyable way for you to hear about what the Managing Editors are obsessed with and/or moping about. —Steve] [Yes, well, as I was getting around to saying:2 I’m joyful, I’m grateful—for our actual thousands of subscribers,3 for having the aid of Julia’s perennial sensitivity and good taste in Poems,4 for Sarah and Grace’s wonderful Children’s Literature recommendations, for everything Hannah does in the twilight world of social media, even for Steve, who is in truth, as he is always saying, “making the WRB happen” (That’s right. —Steve)—and I’m very proud. Everyone I meet—and I’ve met so many wonderful people through this—thinks the WRB is my full-time job, which it certainly isn’t. (Nor is it mine. —Steve) That’s a testimony to everything they’ve done to make this possible every week. I opened WRB—Feb. 5, 2022 writing, “We’re attempting to cultivate a spirit of brevity.” I am very sorry for everything that has happened since then, and I want to make it clear that we have no plans to get better. —Chris]

Links:

In the Times, A. O. Scott on Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe (1952) and its foreshadowing of various modern campus controversies:

Ostensibly “founded in the late 1930s by an experimental educator and lecturer, backed by a group of society-women in Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati,” Jocelyn is the invention of Mary McCarthy, who drew on her experiences teaching at Bard and Sarah Lawrence in the late ’40s. It’s the setting for The Groves of Academe, her 1952 novel about a literature instructor—the sublimely unctuous Henry Mulcahy—fighting to hold onto his job after being denied reappointment by the college president. Enlisting his credulous colleagues as allies in his dubious cause, Mulcahy throws the pastoral campus into turmoil. The plot careens through tense office-hour conclaves and late-night strategy sessions toward a climactic and chaotic symposium on the state of American poetry.

In Intelligencer, Nicholson Baker on the history of UFO sightings and attempts to legitimize them:

This biological weapon, known as the E-77 balloon bomb, had as its primary target the wheat fields of Ukraine. “The anti-crop program is aimed at the bread basket of the Soviet Union,” said an Air Force memo dated December 15, 1951. By March 1953, the CIA, using Project Moby Dick as cover, had set up three balloon-testing and training outposts on the West Coast—two in California and one in Oregon—plus a site in Missouri and one at Moody Air Force Base in Georgia. According to another declassified Air Force memo (I found it in the National Archives), 2,400 test-balloon flights crisscrossed the U.S. in the early ’50s in preparation for the massive biological-warfare attacks planned by the Pentagon for World War III. “On the surface, it appears that the balloon delivery system is feasible,” the memo read.

- on “the shaggy dog novel”:

What other books could we put in the category of Shaggy Dog Novels? Franz Kafka’s The Castle seems like a foundational text here. Kafka takes a straightforward plot of a man on a quest to get into a castle, but then denies the reader the expected resolution. The hero is presented with increasingly bizarre obstacles. The quest can never be completed and no progress can be made. The meaning comes through the very denial of that goal.

[Reading the WRB is like this. —Steve]

In Volume 1 Brooklyn, Ellie Eberlee on reading Woolf directly from her manuscripts:

Maggie Nelson writes about “the pleasure of recognizing that one may have to undergo the same realizations, write the same notes in the margin, return to the same themes in one’s work, relearn the same emotional truths.” She posits that we may have to “write the same book over and over again—not because [we’re] stupid or obstinate or incapable of change, but because such revisitations constitute a life.” The same might be said of reading. Walking out to the library on Saturday mornings, I realized I was going because I’d discovered the pleasure of staging encounters with a self which was at once capricious and constant. I was going, in the most intentional way I’d subconsciously conceived of, to read the same books over and over again, because those were the books by which I had understood myself—into which I had, in effect, inscribed myself—since the age of seventeen. Because such revisitations constitute a life.

Reviews:

In The Baffler, Alexander Wells reviews Jenny Erpenbeck’s latest novel (Kairos, translated by Michael Hoffman, 2023) [An Upcoming book in WRB—June 3, 2023]:

As love novels go, Kairos is strikingly unbalanced. So much more, by weight, is dedicated to the affair’s grim, disturbing coda, the long phase of bitterness, manipulation, and—infuriatingly—nostalgia that follows a few short months of covert bliss. Erpenbeck surely knows that this is wearying, a serious demand on the patience of her readers. One suspects that, like making Hans our Virgil for the Ganymede scene, it’s another of her narrative tricks against nostalgia. It is likely a claim about the GDR, as well—that East Germany’s brief utopian movement, its brilliant and somewhat legitimate founding mythology, was greatly outweighed by interminable stretches of moral and political decay. Hans’s behavior suggestively mirrors that of the GDR regime, being briefly charming before his domineering, accusatory, ideological side takes over. He, like the Party, is a vigorous believer but not much of a listener.

In The Lamp, Chris reviews two recent compilations of Gene Wolfe (The Dead Man and Other Horror Stories, 2023; The Wolfe at the Door, 2023):

Here’s a thesis on Gene Wolfe’s work: he is a storyteller, a tale-teller of the old sort. He all but admits this in his introduction to the collection Endangered Species, when he places us in an uncomfortable position again: “Most important to me, you will be my willing partner in the making of all these stories—for no two readers have ever heard exact the same story, and the real story is a thing that grows between the teller and the listener.” What is growing between us and him? Here’s what I think: Gene Wolfe wants to drive us all a little mad—or at the very least he’s a little mad, and we’re all coming with him.

N.B. (cont.):

“So you want to be an artist. Do you have to start a TikTok?”

In defense of the patty melt. [They’re fine. So are burgers. What are we fighting about here? —Steve] [I feel strongly about this. —Chris]

An investigation into the maximum size of a PDF.

New issues:

The Brooklyn Rail February 2024

The Lamp Issue 21: Lent 2024 [As linked to above.]

The Journal laid off around 20 staffers from its D.C. bureau as part of reorganizing it.

The Messenger shut down after less than a year in operation. R.I.P.

Jordan Hoffman on working there and its final days: “I’ll never forget the day I was told, breathlessly, by the then-head of the entertainment channel that Toni Collette was trending.”

- on its failure:

One of the greatest tragedies of The Messenger is a hypothetical left unfulfilled: What could someone who wasn’t a complete naïf have done with a $50 million investment in a media company? What if an actual innovator with some regard for people’s careers had gotten a crack at building a sustainable media business with that kind of funding? We’ll never know, but we will at least have a new cautionary tale to teach in business classes about how to light $50 million on fire.

[The Managing Editors of the WRB are open to receiving $50 million. —Steve] [I’d take 49 or even 48 million. —Chris]

Marc Jaffe, editor for various publishers and founder of Villard Books and Marc Jaffe Books, died on Sunday, December 31, 2023. R.I.P.

Local:

Hillwood Estate, Museum, and Gardens reopens today after its annual cleaning.

A lecture series on homes and gardens during this month begins on Tuesday, February 6 at 5:30 p.m.

A walking tour of historic D.C. alleys will begin at 909 M Street NW tomorrow, February 4 at 3:30 p.m.

The Mid-Atlantic Symphony will perform at the Academy Art Museum in Easton on Sunday, February 11 at 4 p.m.

The Kreeger Museum will have a monthly jazz concert beginning in March and ending in June.

Poem:

“Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species” by Deborah Digges

Less than half the size

of the Bernini angel, halfway

across the bridge, men, fleshy,

scarred, animal-in-context, swear in three

languages. Harnessed

to the catafalco,

they can only lean out so farover the Tiber to draw

up water in their buckets for

the work at hand, their safety

ropes and pulleys, taut as fish-

line or kitestring in the glare, caged

as they are between the river

and the sky. So lightin years, they sand the wings.

A white dust shadows their bodies,

ghost tourists, pedestrians,

as though, late in the millennium,

some late mortal ceiling

had just been torn a-

way and we can’t help but risenow and rise instead

of fall in the full

sunlight still clinging to the scaffolding.

[This is from Digges’ 1989 Late in the Millennium, her second collection of four. I just started reading it yesterday, alongside her first collection, Vesper Sparrows (1986).

I’m so struck by the long sentences and loping syntax that makes up many of the poems in both of these books. Another poem in this collection, “To Science,” starts this way:

The way love itself unravels like a toy-

sized double helix spiral

you could lay flat against the page

and take a ruler and draw in the staff

and score the DNA, surely

the genes have seasons.

The brown flecks in my mother’s eyes

became my own, my son’s, through adolescence.

Her sentences are once so wandering and, clearly, carefully planned out. Look at, in “Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species,” how she positions the workers on the Ponte Sant’Angelo (less than half the size / of the Bernini angel) before she even introduces them, the men, into the syntax. And then they’re described so vividly: fleshy, / scarred, animal-in-context, swearing in three languages.

It’s a simple poem in its scene—workmen repairing a bridge, sanding the statues—but Digges renders it in lovely detail. She provides such striking images: the white dust covering the workmen until they look like ghost tourists, and the way they stand caged . . . between the river / and the sky. That line, actually, might be my favorite in the poem: and the sky. / So light . . The way that that stanza is enjambed, keeping light on the line next to sky, renders a clear image of light falling onto the bridge. When the next stanza arrives, though, that’s not what’s happening after all. So light // in years, they sand the wings. And yet that image of light carries through to the final moment, with the rise instead / of fall in the full / sunlight still clinging to the scaffolding. There’s such a wonderful sound to those last few lines, too.—Julia]

Upcoming books:

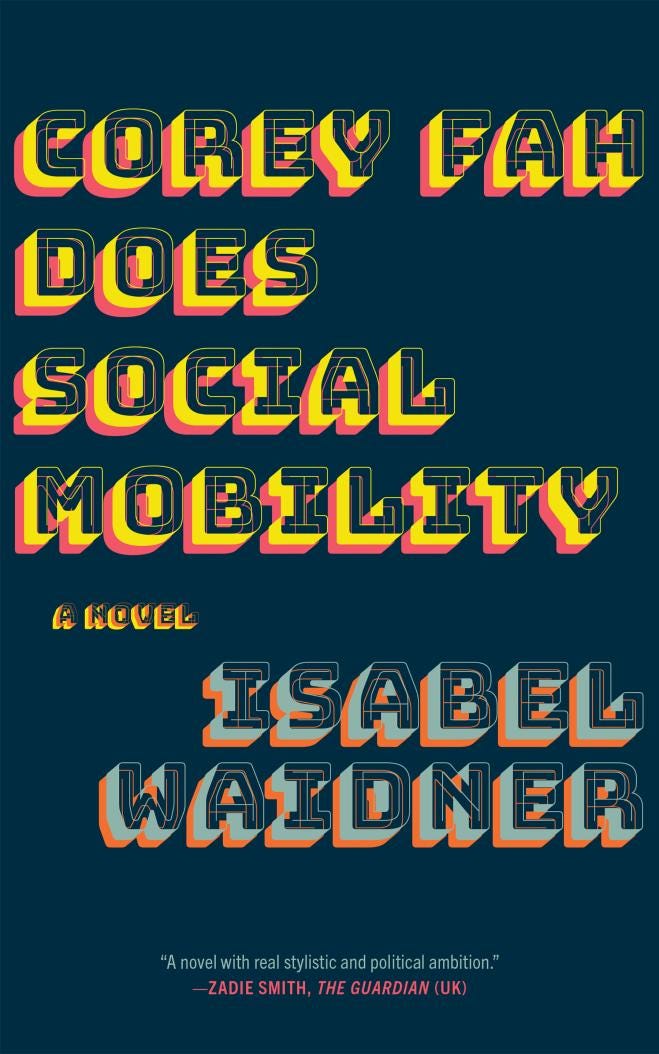

February 6 | Graywolf Press

Corey Fah Does Social Mobility

by Isabel Waidner

From the publisher: This is the story of Corey Fah, a writer who has hit the literary jackpot: their novel has just won the prize for the Fictionalization of Social Evils. But the actual trophy, and with it the funds, hovers peskily out of reach.

Neon-beige, with UFO-like qualities, the elusive trophy leads Corey, with their partner Drew and eight-legged companion Bambi Pavok, on a spectacular quest through their childhood in the Forest and an unlikely stint on reality TV. Navigating those twin horrors, along with wormholes and time loops, Corey learns—the hard way—the difference between a prize and a gift.

Also on Tuesday:

Vintage: Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart and Other Stories by GennaRose Nethercott

From the publisher: The stories in Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart are about the abomination that resides within us all. That churning, clawing, ravenous yearning: the hunger to be held, and seen, and known. And the terror, too: to be loved too well, or not enough, or for long enough. To be laid bare before your sweetheart, to their horror. To be recognized as the monstrous thing you are.

A no-longer-upcoming book that came out Thursday:

Tupelo: Asterism by Ae Hee Lee

From a review by Donald Revell: I have been waiting quite a while for a poet to risk the elegance and gestural audacity of the Baroque upon issues of origin and identity. All too often, these issues vex and distort our poetry. But in Asterism, they amplify the language of Ae Hee Lee onto a ravishing spree of utterance and image. There is great breadth here, and heartening innovation.

What we’re reading:

[Chris’ notes are here continued from Wednesday. —Steve] [Anyway: Repetition. As I’ve commented before, Cavell’s essays are all basically disorganized messes. I first read the essay on The Awful Truth (1937) being pretty strung out, physically, delayed in the Orlando Airport at the beginning of last month. So it’s sat with me in a pretty confused state, and I want to pull out one thread and remove some knots, where Cavell takes up “an ancient question concerning whether the comic resides fundamentally in events or in an attitude toward events.” What I’m interested in is the concept of having a certain comic attitude toward one’s own experience, which Cavell finds in Montaigne:

as if to say: life is hard, but then let us not burden it further by choosing tragically to call it tragic where we are free to choose otherwise. I understand Montaigne's alternative to horror to be the achievement of what he calls at the end a gay and sociable wisdom. I take this gaiety as the attitude on which what I am calling diurnal comedy depends, an attitude toward human life that I learn mostly from Thoreau, and partly from Kierkegaard, to call taking an interest in it. Tragedy is the necessity of having your own experience and learning from it; comedy is the possibility of having it in good time.

To me this seems something like what I attempted to articulate to a reader this week as a habit of being “faithful to one’s experience,” the way one can be true to one’s word. The title of Till We Have Faces (1956) is taken from a reflection on this:

Lightly men talk of saying what they mean. Often when he was teaching me to write in Greek the Fox would say, “Child, to say the very thing you really mean, the whole of it, nothing more or less or other than what you really mean; that's the whole art and joy of words.” A glib saying. When the time comes to you at which you will be forced at last to utter the speech which has lain at the center of your soul for years, which you have, all that time, idiot-like, been saying over and over, you’ll not talk about joy of words. I saw well why the gods do not speak to us openly, nor let us answer. Till that word can be dug out of us, why should they hear the babble that we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?5

I don’t think it’s possible to say what we mean—language is always defeating us there.6 But I do think it is possible to mean what we say, in the sense of binding ourselves to those words we have chosen to give our meaning to. If we can’t speak in accord with how we have lived, we can live in accord with how we have spoken.7 This is just to say that vows are possible.

If we are going to be true to our experience (my roommate, about this, used the language of being integral, of being with integrity), we need to take an interest in our experience and find in it something other than a tragedy, a succession of losses, just as we need to find in what we have said something meaningful for our present conduct even though our words themselves are always a tragedy. We need to find something of the festival, of a comedy, in what has taken place and continues to take place, passing away and being found again: “As redemption by suffering does not depend on something that has already happened, so redemption by happiness does not depend on something that has yet to happen; both depend on a faith in something that is always happening, day by day.” And this is something that needs to be done over and over again, not as a burden of grinding obligation, but “a run” in the everyday: “Not one laugh at life—that would be a laugh of cynicism. But a run of laughs, within life; finding occasions in the way we are together. He is the one with whom that is possible for me, crazy as he is; that is the awful truth.” So, I’m reading Repetition: “For hope is a beckoning fruit that does not satisfy; recollection is petty travel money that does not satisfy; but repetition is the daily bread that satisfies with blessing. When existence has been circumnavigated, it will be manifest whether one has the courage to understand that life is a repetition and has the desire to rejoice in it.”8 —Chris]

Steve, in addition to rereading “Lycidas” and some other shorter poems by Milton, read “Five Types of Lycidas” by M. H. Abrams, as well as the postscript he added a quarter-century later, out of Doing Things With Texts (1989).

[Now, the notes on the connection between Milton and Chris’s recent notes I promised Wednesday. A few times in Pursuits of Happiness Cavell invokes the justification for marriage Milton provides in The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, saying that it is more or less identical to that advanced by the comedies of remarriage under consideration. In that tract, Milton provides God’s reason for creating Eve and glosses it as follows:

From which words so plain, lesse cannot be concluded, nor is by any learned Interpreter, then that in Gods intention a meet and happy conversation is the chiefest and the noblest end of mariage: for we find here no expression so necessarily implying carnall knowledge, as this prevention of lonelines to the mind and spirit of man.

The most obvious way this cashes out in the films, as Cavell notes, is that none of the couples have children. (In The Awful Truth there is a dog who functions either as a dog or as a child substitute depending on the needs of the scene; this is the film’s biggest flaw.) More interesting is its connection to the past of the couples. Chris said on Wednesday:

One of the great themes, of course, for Cavell, is the love relationship grounded in a past (“a pair who recognize themselves as having known one another forever, that is from the beginning, not just in the past but in a period before there was a past, before history”); in the symbolic or literal ways in which the lovers have a past innocence which they are in some way returning to, hopefully, with joy.

Many of the films link this past innocence with childhood, a time before the characters were aware of the games that come with romance, the desire to conceal one’s deficiencies until it’s too late. Having known each other outside that context should serve to prevent what Milton lists as frequent causes of bad marriages, causes that he claims cannot be known in advance:

The sobrest and best govern’d men are least practiz’d in these affairs; and who knowes not that the bashfull mutenes of a virgin may oft-times hide all the unlivelines and naturall sloth which is really unfit for conversation; nor is there that freedom of accesse granted or presum’d, as may suffice to a perfect discerning till too late: and where any indisposition is suspected, what more usuall then the perswasion of friends, that acquaintance, as it increases, will amend all.

Or, to proceed in the opposite direction: if increased acquaintance after marriage is no sure cure, it is necessary to have that acquaintance before marriage; but it is impossible to have that acquaintance before marriage, since the necessary level of intimacy comes only with marriage and the nature of (to use an anachronistic phrase) the dating game implies some concealing of the facts; therefore, there must be a time when these things could be ascertained about the other openly, and that time is childhood. In The Philadelphia Story (1940) Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn “grew up together” and frequently bicker like children—that is, guilelessly—to prove it.

Samson Agonistes approaches these questions through a failed reconciliation between Samson and Dalila, after which Samson says: “Love-quarrels oft in pleasing concord end, / Not wedlock-trechery endangering life.” The test of the relationship, of whether they should get back together or not, is in the results of the quarrel, which is a peculiar kind of conversation particularly open to honesty. During their discussion, Samson tells Dalila “I before all the daughters of my Tribe / And of my Nation chose thee from among / My enemies”—their relationship lacks this ideal past based in childhood openness, and so when they quarrel, as the couples in comedies of remarriage do constantly, what they learn is the extent of their alienation from each other. As if to hammer home the point, the Chorus responds to Samson’s declaration with a long speech during which they say:

What e’re it be, to wisest men and best

Seeming at first all heavenly under virgin veil,

Soft, modest, meek, demure,

Once join’d, the contrary she proves, a thorn

Intestin, far within defensive arms

A cleaving mischief, in his way to vertue

Adverse and turbulent, or by her charms

Draws him awry enslav’d

With dotage, and his sense deprav’d

To folly and shameful deeds which ruin ends.

What Pilot so expert but needs must wreck

Embarqu’d with such a Stears-mate at the Helm?

This is, of course, basically the complaint in The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce I quoted above in verse. Stripped of the overt moralization, it speaks to the fundamental lack of knowledge of the other person that the comedies of remarriage suggest can be overcome through the existence, or creation, of an ideal childhood past. —Steve]

Julia read through Mag Gabbert’s debut poetry collection Sex Depression Animals (2023) [Alright enough of this. —Chris][That’s what I’ve been saying. —Julia], then started Anders Carlson-Wee’s collection Disease of Kings (2023) and Erin Marie Lynch’s debut, Removal Acts (2023). [So far, at least, the latter two seem promising. —Julia] She also finished Love’s Work (1995).

Critical notes:

Merve Emre interviews Andrea Long Chu:

I think in criticism, there is cruelty and there is viciousness. Viciousness is the attack dog that hasn’t eaten in a week, and is drooling and barking and snarling. Cruelty is the person holding the leash. That piece, I think, was vicious. But the viciousness proves that it is not coming from a place of authority, because it leaps into the exacting of violence onto the object. Cruelty says, “Well, what are we going to do about this?” There’s a restraint and a withholding. “I could be hurting you, but I won’t,” or “I won’t hurt you as much as I could.” That is the position I have, I hope, moved toward, as I look at these takedowns I have written.

- on Taylor Swift:

Any appearance of a sexual relationship between two attractive people in public is gonna drive people a little Looney Tunes: It’s gonna give them all kinds of weird feelings of desire and jealousy they don’t understand and want to get rid of. Most normal people just go “Well, isn’t that cute,” and seethe or pine quietly or even unconsciously. Having gone through the Oedipal ordeal, normally socialized people can convert the frustratingly unattainable into more gentle ideations that don’t torment them as much, but will instead support their fantasy life, give them romantic notions, models to emulate, and so forth. You know, the normal ways of relating to movies and pop stars. But since Taylor Swift is the avatar of straight femininity in general, the whole thing touches on the burning core of the real a bit too closely. It’s a little like David Lynch’s universe: on the one hand, there are all these very straight, 1950s motifs, on the other, there’s a psychotic underworld of perverse, obscene enjoyment, relations of de-sublimated domination and power, that the conservatives are perhaps a little too sensitive to now.

- on the vibes of Dorothy Parker:

I wrote down some notes about publishing a while ago and among them was the thought everybody wants to be the Partisan Review but nobody wants to be the Harold Ross New Yorker. That is, “everybody” wants to launch a publication that’s already, in some sense, grown up—one that puts out definitive pieces and devastating critiques, and which publishes the most substantive names of its day. (“Everybody” here is, as always, a vibes-based category.) What you don’t see a lot of is lightness.

- on the demand for content:

When we actually catch people in the wild claiming they’ve been transformed by a piece of content as shared content, it can feel unpleasant to watch. Marvel taught me how to be strong, Jungkook gave me a reason to keep going. This is language from within the logic of fandom, spectacle, mass-cult. By contrast, we don’t feel as weirded out when people talk about being shaped by things outside of the mass-cult, even if they’re things that are popular. It’s not as skin-crawling to hear about the effect The Brothers K had on someone. The less of a mass-cult that is formed around the object, the more unselfconsciously one engages with it. Compare reading Infinite Jest on the subway to reading a book of unfamiliar David Foster Wallace essays on the same subway.

James Duesterberg on Natasha Stagg:

“The more we assign meaning to symbols,” Stagg writes in another essay, “the more we desire the symbols themselves.” In a world increasingly composed of text and images, symbols come to seem less conduits to something else than the final objects of our desire. Media, mediation: this is what we want. This thought is commonly invoked to explain the social anomie of the current generation of hyper-online young people—sending kissy emojis alone in their rooms instead of making out at a party, chasing likes rather than drinking beers. But here it folds back on the question of literary genre and style, of writing itself.

Anything we experience may, depending on the circumstances, help to make us better people, but we have to be disposed to change, willing to change for the better. And maybe one thing art can do is to shape our dispositions, put us in a frame of mind or heart to live differently.

[Of blessed memory

[This being the sap that I didn’t get into at the end of last year.

[!!!

[Most recently on extremely fine display with

in their first Poetry Supplement—I encourage you to tell them how much you enjoyed it (and if you, somehow, did not, keep it to yourself!)[I recall the lines: “I think the sirens in the Odyssey sang the Odyssey, / For there is nothing more seductive, more terrible, / than the story of our own life, the one we do not / want to hear and will do anything to listen to.”

[On this topic, see especially what I quote from Celeste in Critical notes in WRB—Nov. 4, 2023.

[I’ve previously alluded (in an issue of this newsletter that may go down in history as the strangest) to the line Cher delivers in Moonstruck (1987), “Maybe my nature does draw me to you, that doesn’t mean I haveta go with it. I can take hold of myself and I can say yes to some things and no to other things that are gonna ruin everything! I can do that. Otherwise . . . what good is this stupid life that God gave us? I mean, for what?” Of course the reconciliation of this rational hope—to ascend to an objective existence in marriage—with Nic Cage’s response (“love don’t make things nice”) is the whole trouble.

[The Middle English Pearl concludes:

To pay the Prince other sete saghte,

Hit is ful ethe to the god Krystyin.

For I haf founden Hym, bothe day and naghte,

A God, a Lorde, a frende ful fyin.

Over this hyul this lote I laghte

For pyty of my perle enclyin;

And sythen to God I hit bytaghte

In Krystes dere blessyng and myn,

That in the forme of bred and wyn

The preste uus schewes uch a daye.

He gef uus to be His homly hyne

And precious perles unto His pay.