WRB—Feb. 8, 2023

The WRB is Sublime

To do list:

order a tote bag or now a MUG;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, either by placing or responding to one;

and,

Links:

Where to start:

For National Review, Jack Butler on the new Library of America Ray Bradbury volumes:

However capable Bradbury was of matching his contemporaries’ imaginative feats, he was always up to a little bit more. In one of the essays included here, he explains his approach as an author of science fiction and fantasy. It can function “both as fresh entertainment and as morality cloaked in symbol and allegory”; it can make “outsize images of problems so they can be seen and handled from all sides like those Easter balloons strung along the avenue by Macy’s each year”; and it can “deal so strikingly with themes that concern us all today.”

For the New York Times, Sadie Stein on “the essential Colette”:

By turns revolutionary and retrograde, liberated and conservative, a traditionalist who defied labels and loved a title, Colette was nothing if not contradictory. Both her life (81 years long) and her body of work (which exceeded 40 books) were epic, and given that her writing was so often autobiographical, the two were inextricably conflated in the public mind. But if anything, her notoriety obscured the greatness of her prose: Her event-filled life often overshadowed the accomplishments of her best-selling fiction.

Also in the Times, Elisa Gabbert on poetic openings:

Truly great first lines are rare—we don’t often get an “All the new thinking is about loss.” A “Sundays too my father got up early.” A “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.” (The rest of this Robert Herrick poem, except for the title, is forgettable.) They are rare because unnecessary. Most readers will give you a few lines.

Il fumo:

For New Left Review, Becca Rothfeld writes about Italo Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience at 100 years:

Appropriately enough, Zeno’s final confession in Zeno’s Conscience is that the rest of the book is untrue. He concedes that he “invented” everything in his journal, but consoles us, “inventing is a creation, not a lie. Mine were inventions like those of a fever, which walk around the room so that you see them from every side, and then they touch you. They had the solidity, the colour, the insolence of living things”. Zeno himself “literaturizes” constantly. He acts as if he were on the verge of quitting smoking because “the taste of a cigarette is more intense when it’s your last”, and the pretext rearranges the world until it is in fact sharper and more beautiful. A last cigarette is more potent than a normal cigarette, even if it is the first of many.

And for the European Review of Books, Christy Wampole on the same:

These people are paid to think. Their auxiliary tasks are writing and analyzing, organizing, and sharing data. In brain-centric fields, the body is nearly a vestigial organ (except the eyes, required for capturing new information, and the hands, required for typing), so it isn't surprising that the brain and nervous system might begin to go haywire when overtaxed. In his 1962 description of Zeno’s neurosis, the Dante scholar John Freccero unwittingly described many people I know, all potential avid readers of The European Review of Books: “It is Zeno’s intelligence which converts the rhythm of life into disease, by analyzing and dissecting, by searching for stability in the present and substituting self-consciousness for action, chain-smoking for life.” Brain-work puts undue strain on the nervous system. In too high doses, awareness becomes a pathology of the most intractable kind.

Related: [I really want to read this, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how to pay for Dirt anymore. —Chris] N.B.: A psychoanalyst’s office.

Reviews:

One more 100: Italo Calvino. Gustav Jönsson reviews the recently collected uncollected essays (The Written World and the Unwritten World, January) for the Washington Examiner [You can’t buy a lede like this]:

At a party in London recently, an Italian man asked me what I was working on. To my reply that I was writing a review of Italo Calvino’s nonfiction, he said the mere thought of reading Calvino gave him an erection. “That’s very Italian,” I thought. Italy loves its authors. Two years ago, when a German newspaper printed a column criticizing Dante, the outcry among Italians reached the Cabinet in Rome, with the minister of culture urging people to ignore the column. And when Calvino died in 1985, the whole country went into mourning. Gore Vidal recalled that the Italian president had visited Calvino to say his farewells and that “each day for two weeks, bulletins from the hospital at Siena were published.”

[This weekend I was saying, at length, to a reader that someone ought to say that the new Salman Rushdie book is bad. Christmas come early: The Drift come through. —Chris] Zain Khalid for The Drift on Salman Rushdie’s new novel (Victory City, February):

Rushdie’s authorial vices—his moralizing tone, his love of trivia, his chintzy exoticism—have rendered many of his recent novels unreadable. But at his best, Rushdie writes from a perspective between cultural and religious identity, synthesizing the migrant sensibility into a searing, protean critique of the Anglo-imperial world. His finest work is moored to subjects and settings he knows well; it is often about India. My hope was that Victory City, an Indian novel through and through, would mark the return of Rushdie’s critical and creative faculties. No such luck. He has forgone the potent nebulousness of colonialism, displacement, and exile for mannerist expressions of his own prosaic wisdom.

N.B.:

You guys are going to go nuts for this one:

Who is Paolo Dimitrio? For many years, he appeared to be the 63-year-old pizza chef serving up pies to regulars in France’s Saint-Etienne’s Caffe Rossini restaurant while posting pics of his expat life in France to social media. It turns out, however, that the pizza gig was just a decades-long cover for Edgardo Greco, the most recent super boss of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra mob family apprehended by Italian authorities in recent weeks as they’ve accelerated the pursuit of at least four other major mafiosi still on the lamb. Greco was convicted in absentia in 1991 for a double homicide of suspects he had allegedly murdered with iron bars before disposing of their bodies in baths of acid. Authorities discovered Greco’s location after a French newspaper featured his photo in an article touting his dishes with authentic Sicilian flavor. “I only want to offer regional and homemade recipes,” said Dimitrio.

New issue of The Boston Review: “Speculation”

New issue of the LARB Quarterly: “Are you content?” [If I were, would I be writing an email newsletter? —Chris]

Forthcoming spring issue of Oxford American.

The Publication Intensive is a free two-week program in the history and contemporary practice of publication. Applications due March 6.

On Thursday Evening, Second Story Books will be celebrating the life of bookseller Topher Lundell.

Local:

At the Freer Gallery, a recently introduced exhibition: “A Collector’s Eye: Freer in Egypt”

That NGA Carpaccio exhibit [Which closes after this Sunday in case you still need to get after it.] was written up by Andrew Butterfield in the NYRB [This has the “book report” quality our sister publication has been given to more and more recently.]:

Both modes—actuality and fantasy—have elicited from modern viewers the feeling that Carpaccio is ingenuous, unaffected, and sincere, for it seems that he is either telling the truth without embellishment or reciting a tale from the nursery. His is apparently an artless art, and he must be trustworthy and childlike. John Ruskin, who did so much to revive interest in the painter, said his pictures were full of the “extreme joy of childhood.” Henry James called him “the most personal and sociable of artists.” Jan Morris spoke of him as a friend whose art was above all characterized by kindness. They—we—are all beguiled and enchanted.

The Managing Editors have never been “shushed” in the National Gallery of Art.

The Catherine Project is organizing an in-person reading group on War and Peace in Baltimore. Wednesdays at 7 pm, starting March 1. If you’d like to join, write to study@catherineproject.org.

Upcoming book:

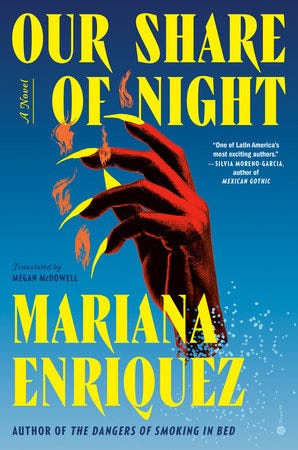

February 7 | Hogarth

Our Share of the Night

by Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell

From the publisher: A young father and son set out on a road trip, devastated by the death of the wife and mother they both loved. United in grief, the pair travel to her ancestral home, where they must confront the terrifying legacy she has bequeathed: a family called the Order that commits unspeakable acts in search of immortality.

For Gaspar, the son, this maniacal cult is his destiny. As the Order tries to pull him into their evil, he and his father take flight, attempting to outrun a powerful clan that will do anything to ensure its own survival. But how far will Gaspar’s father go to protect his child? And can anyone escape their fate?

Moving back and forth in time, from London in the swinging 1960s to the brutal years of Argentina’s military dictatorship and its turbulent aftermath, Our Share of Night is a novel like no other: a family story, a ghost story, a story of the occult and the supernatural, a book about the complexities of love and longing with queer subplots and themes. This is the masterwork of one of Latin America’s most original novelists, “a mesmerizing writer,” says Dave Eggers, “who demands to be read.”

Note on this one David Kurnick from the last days of Bookforum [Which you may remember from last month]. And here’s the Glitzy NYT piece.