WRB—Jan. 21, 2023

Graydon Carter here, Graydon Carter there…

One of the longest journeys in the world is the journey from Northern Virginia to the District of Columbia—or at least from certain neighborhoods in Arlington to certain parts of D.C.. I have made that journey, but it is not from the experience of having made it that I know how very great the distance is, for I started on the road many years before I realized what I was doing, and by the time I did realize it I was for all practical purposes already there.

To do list:

order a tote bag or now a MUG;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, either by placing or responding to one;

and,

Links:

For the Neglected Books blog (Where forgotten books are remembered), Christopher Hawtree un-neglects P.Y. Betts’s novel French Polish (1933):

Diligent curiosity had brought me to this seemingly frivolous perusal of a long-vanished novel—and would take me far from that sedentary perch in Great Russell Street. That winter I was at work compiling and introducing an anthology from the weekly magazine Night and Day, which lasted for only the second half of 1937 in a bid to be a London equivalent — with equally wonderful cartoons—of The New Yorker. Its demise is often attributed to a lawsuit brought against it by Twentieth-Century Fox after co-editor Graham Greene had written in no uncertain terms about the sexual stance displayed by nine-year-old Shirley Temple in Wee Willie Winkie. In fact, funding had been low from the beginning, with modest fees paid to an array of authors who would, around the world, become better known down the years.

There were also some who faded from sight after appearing in such glittering company where they, too, made an equal showing. Among these was P. Y. Betts who wrote entertainingly about French life and food, as well as supplying “A Snob’s Guide to Good Form”, which anticipated Nancy Mitford’s U and Non-U controversy by two decades. What could have become of such a talent? Try as I might, I could not discover anything much about her — and lamented this en passant in the long introduction to the volume which appeared later in the year.

Nicholas Burman has a quick note in Jacobin on Herbert Read:

For Read, the Greeks and the Middle Ages provided examples of epochs in which the artisan was an artist, and when art was part of the quotidian. In To Hell With Culture, he posits that “culture” began with the Romans, those “first large-scale capitalists […] who turned culture into a commodity” by “importing [their] culture” and who “set a standard to which all newly civilized people aspired.” “Culture” reemerged as a concept in Britain during the Romantic era, thanks to industrial England’s need to hark back to the days before the birth of machines and mass production.

The NYRB Saturday interview this morning was a very interesting exchange with archetechture critic Martin Filler:

Rococo and Art Nouveau took their primary cues straight from the natural world, but did so with a determined playfulness generally not encountered in high-style design. The main difference between them was psychological. Rococo aimed for a carefree lightness, whereas Art Nouveau exuded an anxious ambivalence. Both employed similar motifs, such as sinuously swirling lines and vertiginous perspective, and ignored the Classical ordering systems that were reintroduced during the Renaissance. The relaxed rules of decorum that typified both Rococo and Art Nouveau in due course prompted the equal and opposite reaction promised by the laws of physics: each movement in turn was superseded by a Neoclassical correction that sought to stabilize wayward notions of design with historically inspired schemes patterned after Classical antiquity and believed to be more suitable for the public realm.

Reviews

Two new reviews of the A.E. Stallings selected volume (This Afterlife, December) from last month (which we quite enjoyed):

It is tempting to classify these poems in the popular contemporary genre of feminist retellings of myth, but while the narrative personae are enhanced by Stallings’s psychological acuity, such a designation would nonetheless underrate the degree to which such stories form, in a place like Greece, part of a living culture. Just as paganism was far more welcoming of new gods into the pantheon than monotheism, Greco-Roman mythography has historically been far more open to narrative variants than biblical mythography. (“Four Fibs,” a poem that exposes the ”genesis of the lie” about Eve’s temptation and the Fall, is thus, of necessity, much more antagonistic toward its source material.) “Eurydice’s Footnote” and “The Wife of the Man of Many Wiles” could be described as modernizations, but they could just as easily be described as continuations of a literary practice that dates back to the classical period. After all, it is only in the land of the dead, as Stallings writes, that “things can be re-invented no longer.”

And David Orr in the Times: “The main thing Stallings has going for her is that she’s good at writing poems. In particular, she’s good at writing the sort of poetry that evokes the word ‘good,’ rather than, for instance, ‘brave’ or ‘disorienting.’”

Along the same lines: Last summer, NYRB’s poetry imprint published a new selection and translation of Arthur Rimbaud by Mark Polizzotti (The Drunken Boat: Selected Writings, July 2022). Reviewed this week in LRB by Michael Wood, we read:

And all these remarks point to one of Rimbaud’s favourite and most powerful literary moves: the flight into a mythology that seems less mythological every minute, not literal but definitely real. There is, for example, the Christian framework of hell and sin. Rimbaud addresses the devil as “dear Satan,” a personage who momentarily becomes the reader, since “these hideous pages from my notebooks of the damned” are “torn out” for him. There is the colonial framework in which the natives with whom Rimbaud identifies have “always been of inferior race.” Later on he dramatises the recurring invasive moment: “The white men have landed. Cannons! We must submit to baptism, wear clothes, go to work.” And there is also the myth of what Rimbaud calls “the decline of the Orient.” Everything the West does is far from “the thinking and wisdom of the East, the primary fatherland. Why a modern world at all, if it invents such poisons!” Rimbaud rebukes both clerics and philosophers, who don’t see what they are missing, don’t realise that their ostensible progressive gain is all loss. “You are in the West, but you’re free to live in your East, however ancient you need it to be.” We see why the Beats loved Rimbaud.

Wednesday’s Upcoming book was The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier. For Gawker, Charlie Lee reviews: “The grim achievement of Mauvignier’s seething, recursive, semi-improvisational style lies in how he manages to portray a muddled mind—in this case, Patrice’s almost hallucinatory misogyny and the agonized passivity of his desires—with precise lucidity.”

And Sam Sacks in the Journal today: “This is worth a warning: Mr. Mauvignier follows in a prestigious French tradition of stylized improvisations on popular genre forms and The Birthday Party is not a book to pick up if you want a perfectly executed thriller. It is instead a book about character. Its tensions arise less from the question of what will happen at the end than of who each person will become once all the secrets are out.”

And in the newest issue of Harpers, Wyatt Mason reviews a recent book about Predator, the 1987 action movie (Predator: A Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession, September 2022):

No irony. Into our hearts: that’s where the belief in an action movie hits us, in our bodies, in the same way that a bassline by any epic rock band of my young adulthood or yours, heard live, does. It generates a feeling that makes, somehow, your heart grow three sizes in time for Christmas Day, so long as the fundamentally derivative thing moves from the mediocrity that imitation all but guarantees to something, somehow, good.

N.B.:

Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice will be at the National Gallery of Art through February 12. “Victorian literary giants John Ruskin, Henry James, and Marcel Proust held Carpaccio’s narrative art in the highest regard.”

“The novel is almost 600 pages long, and the narration loops back on itself in a way that not only builds suspense, but also creates a visceral sensation of the slowness of time for a 17-year-old who feels trapped in a life that is not his own.” [Okay. —Chris] [Forgive my vulgarity, but I’ve been misreading the “d” in the novel’s title as a “t” this whole time. —Nic]

Department of Style:

This David Owen gripe caused quite a bit of controversy among some readers over lunch this past weekend.

Dan Stahl reviews the new edition of Garner’s. The singular ‘they’ is in.

“The word’s meaning has ooched along since James’s time—like ‘nice’—through a series of conceptual jumps. That which evokes wonder is, after all, likely something you think of as markedly pleasing, and thus to us today, ‘wonderful’ evokes the pleasure more than the surprise.” (John McWhorter, NYT) [I think this is one of the great hidden pleasures that recommends a wide habit of reading: growing in sensitivity to the possibilities of the language. —Chris]

Robert Cottrell defends Orwell against David Hart:

When I look again now at Orwell’s rules in the light of Hart’s critique, I think of H.L. Mencken’s axiom: “There is a solution to every problem: simple, quick, and wrong”.

Orwell's rules are simple and quick. They are not absolutely wrong in themselves, but they are grossly inadequate.

Hart’s rules are not simple and quick. They are complicated and time-consuming. They are also so impractical that their rightness or wrongness scarcely matters. They are far worse.And in response, Henry Oliver: “We are surrounded by obviously middle-class people who insist on their working class credentials today. Orwell was like that, but upper class, and his rules reflect some of that confuscation. It was part of his being an upper-class intellectual that he had to demur his own status.”

Department of Gripping Reads:

“Yes, I Judge Books by their Cover” Étienne Fortier-Dubois: “I would take refuge in a French-language bookstore, where the soft off-white tones are calming, where the artwork (when it even exists) is unthreatening. There is color and there is texture, but everything is understated, as if it wouldn’t do to insist too much on the graphic design. This is literature, after all — the written word is king.”

Dan Kois’ novel came out a few days ago and is called Vintage Contemporaries, which is a pretty clever title. He wrote up a little appreciation of the Vintage Contemporaries line cover aesthetic too.

“It took Joyce 17 years to write the Wake. Liam Heneghan has a foolproof plan to read it just as fast.”

The January 2023 issue of the Capitol Hill Citizen is available to order now. We will quote their pitch in full:

For a donation of $5 or more to cover shipping and handling, we will mail to you a printed copy of the 40-page January 2023 issue of the Capitol Hill Citizen, featuring articles a by Ralph Nader and Dennis Kucinich, question/answer format interviews with Chas Freeman, Clara Mattei, and Emily Jashinsky, a front page investigative article titled “The Thermal Annihilation of Steven Dierkes,” and a back page article titled “Confessions of a West Virginia Starbucks Wage Slave.”

The 2023 Rhina Espaillat Poetry Award is open for submissions.

Triple Canopy is seeking a deputy director.

Upcoming book:

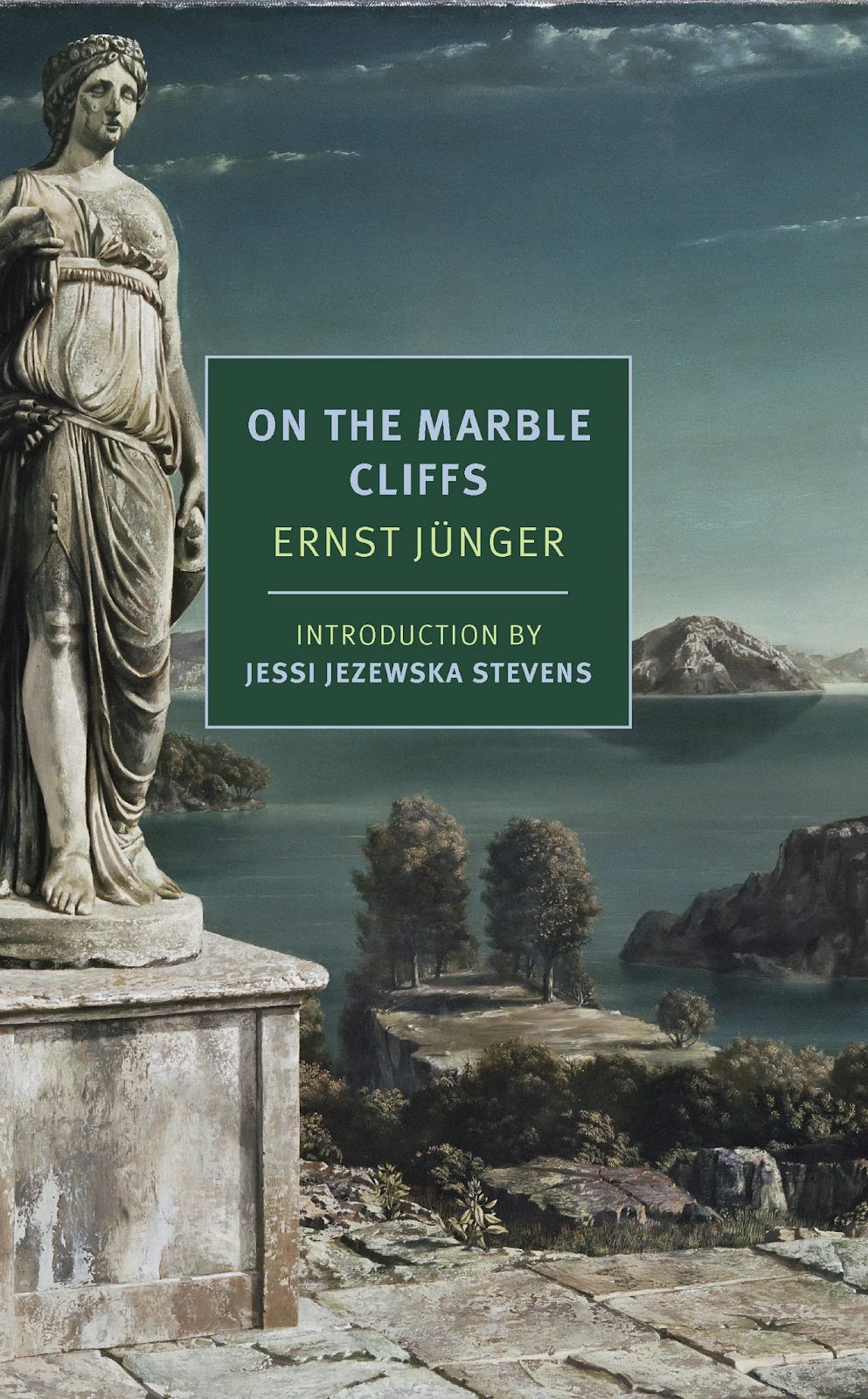

January 31 | NRYB Classics

On the Marble Cliffs

by Ernst Jünger, translated from the German by Tess Lewis

From the publisher: Set in a world of its own, Ernst Jünger’s On the Marble Cliffs is both a mesmerizing work of fantasy and an allegory of the advent of fascism. The narrator of the book and his brother, Otho, live in an ancient house carved out of the great marble cliffs that overlook the Marina, a great and beautiful lake that is surrounded by a peaceable land of ancient cities and temples and flourishing vineyards. To the north of the cliffs are the grasslands of the Campagna, occupied by herders. North of that, the great forest begins. There the brutal Head Forester rules, abetted by the warrior bands of the Mauretanians.

The brothers have seen all too much of war. Their youth was consumed in fighting. Now they have resolved to live quietly, studying botany, adding to their herbarium, consulting the books in their library, involving themselves in the timeless pursuit of knowledge. However, rumors of dark deeds begin to reach them in their sanctuary. Agents of the Head Forester are infiltrating the peaceful provinces he views with contempt, while peace itself, it seems, may only be a mask for heedlessness.

Tess Lewis’s new translation of Jünger’s sinister fable of 1939 brings out all of this legendary book’s dark luster.