WRB—Jan. 27, 2024

Faces for radio

I did not forget to tell you the Washington Review of Books. Every week I tell you the same shit, and every week you forget half of what I say. Tomorrow first thing, you go down to the newsstand, and you get the Washington Review of Books. And Liberties, too, which you also managed to forget.

N.B.:

The second WRB x Liberties salon will take place this evening at 8:30 p.m. and will attempt to answer the question: Is forgiveness possible? If you are interested in attending, please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

In The Baffler, George Scialabba asks “what are intellectuals good for?” [Intellectuals are best seen and not heard. —Chris] [Intellectuals have faces for radio. And voices for biweekly books and culture newsletters. —Steve]:

Why write, then, if failure and frustration are virtually inevitable? Underneath the usual reasons—vanity, righteous indignation, a simple pleasure in fashioning sentences—I believe there’s usually gratitude. From admired writers we’ve received a gift that we’re eager to pass on. They model probity, fearlessness, tact; they make the intellectual virtues irresistible and their exercise compelling. To impart to even a few readers my intense and complicated affection for Serge and Orwell and Pasolini, Trilling and Illich and I. F. Stone, seems a duty both to them and to those readers. To help install figures like these in our culture’s permanent memory is one responsibility of us lesser intellectuals. (And to let a little air out of the reputations of William F. Buckley and Irving Kristol is also worthwhile, and very satisfying.)

In The New Criterion, Joshua T. Katz on what Homer has meant to people over the past three thousand years:

Why would Cicero have cared so much about these words? What are they all about? The verse appears twice in the Iliad, both times in the mouth of Hector, the greatest of the Trojan heroes. Hector speaks it first in one of the most moving scenes in the epic. Toward the end of Book 6, Andromache, Hector’s dear wife, begs him not to return to war but to stay behind lest she be widowed and their son orphaned. He is sorely tempted, for he loves his family, but the honorable thing is to fight to the death. And this is what he says: “I feel dreadful shame before the Trojan men and the Trojan women in their trailing robes if like a coward [the word he uses is kakos, literally ‘a bad man’] I skulk apart from war.” Then, in Book 22, Hector’s other two closest family members, his parents Priam and Hekabe, beg him to retreat. He refuses, says the same words to himself—and goes to meet his fate.

In The Paris Review, Sean Thor Conroe on reading Jon Fosse’s Septology (2022), set in the seven days before Christmas, during Advent:

For Fosse’s protagonist, belief is completely private and beyond reason. Asle’s faith is one of someone trying to understand the inexplicable loss of a loved one. For Asle, God—or any object of belief—is metaphysically real if and only if you put words to your belief. Like how he speaks to Ales still, how he believes he does yet needn’t explain it: he knows he’s her angel and she is his, since “for an angel to exist you have to believe it does, and you have to have a word for it, the word angel, and if you don’t believe that God exists, well then God doesn’t exist.” When I read this, I think of what Jarrod said—that Fosse is either for you or he’s not, you either get it or you don’t, and no one can convince anyone else of anything they don’t want to believe anyway.

In Comment, Matthew J. Milliner on his trip to India to visit a Christian ashram:

The Indian Catholics who now run Shantivanam have picked up where the European founders concluded, and they’ve learned some lessons along the way. One of the monks told me that even if a Christian ashram must be centered on Jesus, the late Bede Griffiths had (somewhat unwillingly) become a guru. This monk described to me Griffiths’s foibles without in any way maligning his character. The lesson was clear: keeping Jesus Christ, and not some other personality, at the center takes serious work—the work of shunning celebrity and getting out of the way. This is the kind of labor that the current monks of Shantivanam seem eager to undertake. This insight, moreover, is materially expressed. It is fascinating to compare the marble statue of the guru Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950) at his ashram in Tiruvannamalai, swarming with meditating Westerners, with the similar marble statue at Shantivanam of Jesus the guru, in the lotus pose of course.

In Tablet, Yehuda Fogel on Rilke’s “Ninth Elegy” from the Duino Elegies and the deaths of his grandparents:

We cannot impress the angels of the next world with deep feelings and memories, for the angel “feels more sensitively” in this realm, whereas we are just beginners. It is only with the “simple / thing that is shaped in passing from father to son, / that lives near our hands and eyes as our very own” that we can awe the angel.

Things can be happy, blameless, and ours, and “even the lamentation of sorrow purely decides / to take form, serve as a thing, or dies / in a thing.” The things, too, are transient. My mother looks around the room at dinner one night and tells me that every corner of this house is full of memories. If they meet the angels, I hope my grandmother brings her cottage cheese tin, and my grandfather his set of Talmud.

In Commonweal, William Giraldi provides a history of ecstasy:

Sir Thomas Browne’s line in Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial, “Ready to be any thing, in the ecstasy of being ever,” is an apt summation of the mystic’s transcendent experience. This is what the believer seeks in ecstasy: the sense of kinship with a reciprocal cosmos governed by a benevolent God or, for the Dionysian cults, with a wilderness resistant to taming. Ecstasy is at bottom escapist, a respite from the world of getting and having, of degradation and decay. It’s also an avenue for enlargement of the soul and enhancement of the sensory. There’s a section in Centuries of Meditations by the seventeenth-century English mystic Thomas Traherne in which he anticipates Wordsworth when writing about a stretch of the greenest trees he’d ever seen: the trees “transported and ravished me, their sweetness and unusual beauty made my heart to leap, and almost mad with ecstasy, they were such strange and wonderful things.” The strange, the wonderful, the ravishment.

In our sister publication on the Hudson, Peter Brown on an exhibit of art at the Met from Byzantium and the African world that interacted with it:

This sense of timeless presences also explains the display of “magical” scrolls at the end of the exhibition. These scrolls have done much to foster the impression of Ethiopia as a somewhat spooky generator of “primitive” art. They are no such thing. They are detailed maps of an unseen world. They reveal an entire invisible counterkingdom of malevolent presences held in check (and only just) by regiments of angels and by a powerful company of saints.

Such scrolls were by no means restricted to Ethiopian Christians. The worldview behind them was taken for granted by Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Long lists of spells are the advice columns of the hopes and fears of believers of all faiths throughout Africa and the Middle East. In Coptic Egypt, one petitioner is told “how to acquire a beautiful singing voice.” Other spells promise to charm the hearts of judges or to ensure that a loss of memory—a senior moment—falls on one’s opponent in the middle of his speech. Identical spells can be found in the papyri of Greco-Roman Egypt. They take us back to the noisy courtrooms of ancient Rome. In the great books of magic, the ancient world never died.

Reviews:

In the local Post, becca rothfeld reviews Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries (February 6) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Jan. 20, 2024.]:

The champions of Oulipo explicitly emphasized syntax over semantics, and Heti’s work, too, declares itself to be an adventure in form. The repetitions are as lulling as a litany. “Do we have to suffer until the end of history? Does he die, drowning, trying to kiss himself?” “I love how I don’t know his face yet. I love that phrase of the art critic, I write poetry for my assistants. I love the entire universe and everything in it.” I love, I love, I love. “He” begins sentences for four pages, “she” begins them for five.

But what, exactly, do these enumerations of echoes teach?

In The Atlantic, Stephen Kearse reviews an anthology of horror by Black authors (Out There Screaming, 2023):

Violet Allen’s “The Other One,” a standout in the collection, centers on the nervous and heartbroken wreck Angela, a grad student who pines for Oglethorpe, an ex who ended their relationship abruptly. When she texts him during a spell of insomnia weeks after the breakup, his reply pulls her into a bizarre love triangle. “lol, why are u texting my boyfriend?” the message—clearly not written by him—reads. The offbeat text exchange that follows nimbly swings from jealous bickering to horrific bartering. The new girlfriend, who is hilariously droll, sends a picture and then a video of Oglethorpe’s removed heart, which sits on a coffee table “beating. Slowly, subtly, but undeniably. Thump, thump, thump, a little burble of blood spilling out each time.”

In The University Bookman, Elizabeth Bittner reviews David Lane’s retelling of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice (The Tragedy of Orpheus and the Maenads (and A Young Poet's Elegy to the Court of God, 2023):

Immoderate enjoyment of wine has led to destruction as surely as the immoderate indulgence of grief. Had Orpheus minded the admonitions of the muses, Apollo, or Tiresias, he would not have fallen afoul of the maenads. Had the maenads not succumbed to the allurements of Dionysius and his wine, they would have kept themselves from murder. However, as Lane told us from the beginning, this is a tragic love story. One characteristic of tragedy is that the tragic action is magnified and unstoppable, rushing headlong to its bitter end. Apollo then addresses the maenads: “Suggestion loves to shroud her darkling; much / She lowers at the poet recreant / Would try the cerements of her nemesis, / Bright clarity, she’d keep interred.” He continues: “In arrogance thou dared’st say within / Thy heart, ‘Be banished thought and story both; / Come eremitic image, emblem of / My state of sadness; furl discursion and / The story till I make an image bold.’” The dimming of clarity and the banishment of thought join to form the tragic current running through the action of this play. The “image bold” becomes a god to Orpheus and the maenads both.

N.B. (cont.):

Trends in restaurant menus.

The life and death of the computer mouse.

Orion magazine is looking for pictures of puddles.

An interview with Dan Sinykin, author of Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature (2023) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Oct. 4, 2023.]

On reading lists.

Henry Oliver provides thirty facts about Romeo and Juliet. [Good play. —Steve]

Local:

Carolyn Drake and Susan Meiselas will discuss the photography of Dorothea Lange at the National Gallery of art tomorrow, January 28 at 12 p.m.

Music by Mozart will be presented at the Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper exhibition at the National Gallery of Art tomorrow, January 28 at 1 p.m. and 3 p.m.

Adam Shatz will be speaking about his new book, The Rebel's Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon (January 23), at Politics and Prose tomorrow, January 28 at 3 p.m.

Poem:

“The Bat” by Olivia Sokolowski

The bat is hideous I love him so much a fact:

if you stepped on a bat in front of me I’d kill youtwice like a villain in a hot blue tailcoat the night

floats its cream moon in ichor orichalcum the batis happy in the dark like me smoking a long cigar

at the coffee table watching another mansion tourwhich culminates descending into a private

nightclub red velvet ropes the ideal of luxuryis to vanish inside amenities like the Batcave

or the Glacier Express my train of thought keeps duckinginto tunnels rare glassware sparking like crickets hey

have you ever been at a party and just needed to hide?have you ever been at your own party and just needed

to hide? I feel like boarding a plane alone in a black suitwith no luggage and wherever I land I’ll get a job

for a secret society gently smuggling fat envelopesfrom a lush hotel into the dark garden lights teal

and red fig trees I think I’ll live in the hour deepas a plum seed troubling the sky for a little moth-wing

and sniffing my flightpath like the bat I’ll have everythingin my grand coaly wings respect fear and when I open

my mouth all these high squeaky sounds like tear out

[This is from the new issue of Blackbird literary journal. I have been thinking about the first line of this poem all week. I like how, despite that a fact is grammatically linked to if you stepped in front of a bat . . . the way the lines are enjambed link it back to I love him so much. That first line functions as a tight unit, and I think it’s so fun. —Julia]

Upcoming book:

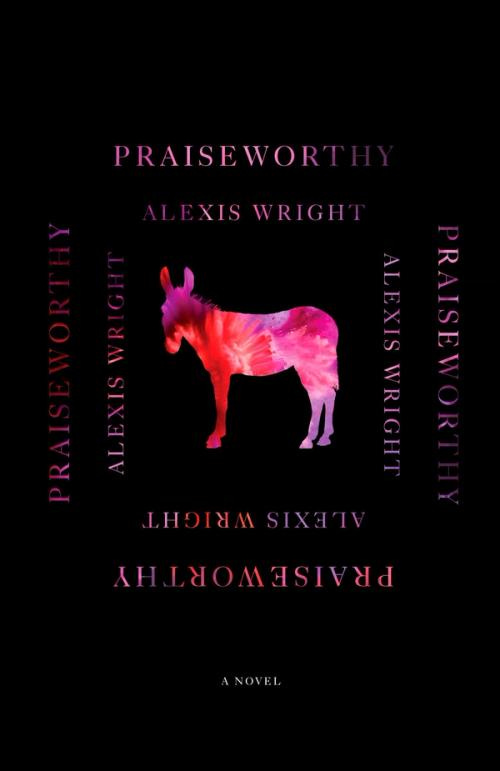

February 6 | New Directions

Praiseworthy

by Alexis Wright

From the publisher: In a small town in the north of Australia, a mysterious cloud heralds both an ecological catastrophe and a gathering of their ancestors. A crazed visionary looks to donkeys to solve the global climate crisis and the economic dependency of the Aboriginal people. His wife, seeking solace from his madness, follows the dance of butterflies and scours the internet to find out how her Aboriginal/Chinese family could be repatriated to China. One of their sons, named Aboriginal Sovereignty, is determined to commit suicide. The other, Tommyhawk, wishes his brother dead so that he can pursue his dream of becoming white and powerful.

Praiseworthy is an epic which pushes allegory and language to their limit; a unique masterpiece that bends time and reality, opening new literary vistas; a cry of outrage against oppression and disadvantage; and a fable for the end of days.

What we’re reading:

Chris started reading (finally) Gravity and Grace. [I’m still reading Mansfield Park, but I’m not loving it! Yes, I’ve read the Trilling essay. —Chris] [I have also read the Trilling essay, and I love Mansfield Park. In the paragraph where Trilling claims “Nobody, I believe, has ever found it possible to like the heroine of Mansfield Park,” he also says “We admire Milton only if we believe with Blake that he was of the Devil’s party, of which we are fellow travelers.” I made some notes on that connection in WRB—Jan. 17, 2024. —Steve] He is also rereading Till We Have Faces.

Steve is still making his way through Stanley Fish’s How Milton Works (2001), in connection with which he read Comus. [More on that in Critical notes.] He also checked the notes in Songs That Saved Your Life: The Art of The Smiths 1982-87 (by Simon Goddard, 2002, 2013) for a few of the songs.

Julia hasn’t read much anything of note in the past couple of days, other than a few more poems from Icehouse Lights.

Critical notes:

[In Comus the attendant Spirit is given a song to call the nymph Sabrina:

Sabrina fair

Listen where thou art sitting

Under the glassie, cool, translucent wave,

In twisted braids of Lillies knitting

The loose train of thy amber-dropping hair,

Listen for dear honours sake,

Goddess of the silver lake,

Listen and save.

And she replies with one of her own:

By the rushy-fringed bank,

Where grows the Willow and the Osier dank,

My sliding Chariot stayes,

Thick set with Agat and the azurn sheen

Of Turkis blew, and Emrauld green

That in the channell strayes,

Whilst from off the waters fleet

Thus I set my printless feet

O’re the Cowslips Velvet head,

That bends not as I tread,

Gentle swain at thy request

I am here.

I share these in part because they’re absolutely lovely. Lines 3-6 of Sabrina’s song have been in my head all day.

Fish discusses repeatedly the importance of seeing in Comus; what, and how, the characters see emerges from their worldview (meant very literally there). “Unto the pure all things are pure,” in other words, or, as the elder brother puts it to the younger brother, “He that has light within his own cleer brest / May sit i’th center, and enjoy bright day.”

But beyond that seeing is also a question of attention; the elder brother understands virtue better than the younger brother because he has given it more consideration. In the songs Milton underlines the difference with the description of color. To the attendant spirit, the water is merely translucent and silver, but the nymph whose water it is can discern not just more colors but finer distinctions within the colors—“Turkis blew, and Emrauld green.” —Steve]

This was an intimate negotiation which necessitated the beautiful loneliness of the single skull. Is it any wonder that a notion of inviolate human rights defined in terms of the independence of the mind followed the emergence of silent reading? What such a space allowed for was the establishment of a kingdom of the solitary reader, content to generate her own meanings from the book, to be inspired or disgusted, illuminated or enraged, convinced or informed on her own terms.

In a sense, the elevation of Gaelic to the status of Scotland’s national tongue is the culmination of a long romantic tradition celebrating the Highlands and Scotland’s Celtic heritage in an almost purely symbolic form that does not actually threaten the fundamentally English nature of modern Scotland. It is a position afforded to Gaelic purely by sentiment rather than reality—a cultural nationalism that long post-dates Scotland’s union with England. There are about as many Polish-speakers as Gaelic-speakers in Scotland today and both pale in comparison to the one and a half million that claim to speak Scots as their native language.