WRB—Jan. 6, 2024

“a story of a failed relationship”

Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch Hall, in Somersetshire, was a man who, for his own amusement, never took up any reading but the Washington Review of Books; there he found occupation for an idle hour, and consolation in a distressed one; there his faculties were roused into admiration and respect, by contemplating the limited remnant of the earliest books; there any unwelcome sensations, arising from domestic affairs changed naturally into pity and contempt as he turned over the almost endless creations of the literary world; and there, if every other link were powerless, he could read the Critical notes with an interest which never failed.

Links:

We have all felt slightly haunted in a used bookstore—all those inscriptions on front pages and mementos used as bookmarks and left in there. [Every copy of Jane Austen showing hardly any wear is a story of a failed relationship. —Steve] But it goes beyond that, and Jeremy Wikeley has more on the experience in The London Magazine:

Then again, even here, some element of wishful thinking is involved. Second-handers aren’t so much checking out of consumer society as poking around in its entrails. Anyone who rummages around in junk shops and markets knows the feeling: at any moment, you might find something special, something overlooked, something placed there just for you. But the stock of a second-hand bookshop is not an infinite library—it’s a record of what has been read already. Sometimes I worry that by spending so much time with my nose in old books I am not only accepting the reading habits of the twentieth century, with all the exclusions that implies (white, male, safe. . .), but hankering after them. None of this is the fault of the books themselves. The second-hand trade might be a kind of selective memory, but at least it remembers. Perhaps they are even more important now, when the other ways in which cultures form their medium-term memory have all but disappeared.

Kate Briggs and Lisa Robertson have a conversation in Granta about the work of writing novels. Briggs:

And acts of description can act as little tools, capable of effecting minor or major adjustments—re-presenting the trivial as vital, the exhausted terrain as barely contemplated—it follows that description is important work. It’s not just padding work or embroidery work. (I say this with my tongue firmly in my cheek, aware of your lifelong interest in dressmaking, knowing very well that you’d never characterize padding or embroidery as unimportant.) I would locate the ethics of description in taking this work on, by which I mean, in taking this emancipatory potential seriously, as part of a writing practice, and a teaching practice.

The Internet may eat our personalities and identities eventually. Philip Roth suffered an even worse fate: having his personality and identity eaten by novelists. In The Atlantic, Adam Langer on the works responsible for that:

Clearly, there is something in this Roth, this exemplar of the brash, outspoken truth-teller with blazing intelligence, rapier wit, and voracious intellectual and sexual appetites, that has managed to endure. His humor, his audacity, his fearlessness and his willingness to offend, so inescapably present in the second half of the 20th century, are all sorely lacking today, which is probably why so many, including Taranto, have felt a need to resurrect him.

And yet, despite the seemingly constant presence of these fictionalized Philip Roths, it’s worth asking now, five years after Roth’s death, whether they have eclipsed the actual work that Roth produced, or any true reckoning with the man himself. Outside of the syllabi of 20th-century-Jewish-American-novel courses and a few short stories (the early, funny ones) in high-school anthologies, will the man’s literary output enjoy the same immortality as that of the persona he created?

In the Times, Joshua Barone on the friendship of Willa Cather and Yehudi Menuhin:

When Menuhin was navigating young love, Cather was a font of advice—“I always have your future very much at heart,” she told him in one letter—and gushed over his marriage to Nola Nicholas. “No artist ever made such a fortunate marriage,” Cather wrote to her friend Zoë Akins. “Yehudi loves goodness more than anything, (I mean beautiful goodness) and she has it.”

Reviews:

For the Book Post, April Bernard reviews two new sets of translations of Colette’s mid-career novels Chéri and The End of Chéri (translated by Rachel Coreau, 2023; translated by Paul Eprile, 2022):

To be such a chronicler of the sensual, of course, Colette must have loved all these delights of the haute bourgeoisie; what astonishes in the pages of these, her two most significant works of fiction, is the judgment also implicitly leveled at material pleasure—that it cannot substitute for actual meaning. Colette’s characters know so little of things other than surfaces, that when they find themselves with real feelings, the only possible outcome is disaster.

[I’ve accepted that I’m going to spend 2024 reading everything Colette ever wrote. I went with the Eprile translation. —Julia]

In the TLS, Caroline Moorehead reviews two works by Michele Mari, recently translated by Brian Robert Moore (You, Bleeding Childhood, 1997, 2023; Verdigris, 2007, January 2):

Mari’s seventh novel, Verdigris, returns us to childhood: it tells the story of a fifty-year-old man reflecting on his life as a thirteen-year-old boy in his grandparents’ house in the country—a place to which he frequently returns in his short stories. Here, the narrator, also called Michele, makes friends with the gardener, Felice, a man of exceptional ugliness, His face, badly scarred by smallpox, sports a large purple birthmark, a nose that is knobbly and sponge-like, and eyes that ooze. Felice is rapidly losing his memory and the boy sets out on a mission to help him hang on to what he has left through associations and word clues. In the process a great murky past seeps out, not least the discovery of three skeletons in uniform—the remains of German soldiers shot by Felice and his partisan friends during the closing days of the Second World War—along with many other bodies buried in the garden, casualties of fascist skirmishes. Verdigris, too, is shot through with repellent images. Ghosts, monsters, riffs on Pushkin and Aeschylus, and musings on guilt, shame and love abound. Searching for himself, friendless, Michele struggles to fill the vast emptiness inside.

In Commonweal, Phil Klay reviews Ishion Hutchinson’s book of poetry about the First World War (School of Instructions, 2023) [One of the Upcoming books in WRB—Nov. 11, 2023.]:

Enter Ishion Hutchinson. School of Instructions emerged when the Imperial War Museum in London commissioned Hutchinson to do research in 2016 on West Indian participation in the First World War. Perhaps they thought they’d get a poet “recovering forgotten histories” by making stuff up. But Hutchinson is a reader not only of Jones but also of the great English poet Geoffrey Hill. He is acutely conscious of how we project ourselves into the past, but also of how the past blends continually, and complexly, into the present, inaccessible and yet constitutive of our very being. Instead of an imagined infantryman fighting in the Middle Eastern campaign—the only campaign in which West Indian troops saw combat—Hutchinson centers his poem on Godspeed, a boy attending a strict school in rural Jamaica in the 1990s, reading his Britannia and communing with the past. The narrative of the soldiers is told at a cool distance, often as if scanning archival reports of troop movements, while the Godspeed sections this narrative bleeds into allow for the history to become tactile: “Brittle bible sheets of his Britannica ached countries / under his thumbs. Uris acid steamed off skulls between / UMBRELLA HILL and the tinfoil sea at SHEIKH / HASSAN which was successfully assaulted and held by / the battalion. He lifted his fingers there were new / borders and some countries had changed their names.”

In the local Post, Mark Athitakis reviews Cynthia Zarin’s debut novel (Inverno, January 9):

But this is very much Zarin’s book, marked by a lyricism that turns its deliberate disarray into a kind of poetic logic—Caroline and Alastair’s lives are like line breaks, snapped off in unexpected places. Alastair’s instinct for self-sabotage is severe; we learn that he has intentionally infected himself with poison ivy and flagellated himself with a belt. Caroline describes him, at one point, as a “madman.” But in the moments when their lives brush together, all that pain practically sings: When “Caroline put her arms around Alastair steamy from the shower, his hand at his throat where he had just loosened his tie, she felt the small lizard of fear, a tiny hunch, skitter across his shoulder blades.” The mood is so gentle yet intense that Caroline kissing his shirt on the shoulder feels like a deeply erotic act.

N.B.:

The short life of The Paris Metro.

The London Magazine has announced the launch of its Poetry Prize.

The Dial is hiring an editor.

New LARB Quarterly.

Local:

“At least 240 Post writers, columnists, editors, and other employees on the business side were expected to leave in the final days of 2023, significantly reshaping the paper in ways that aren’t yet fully realized.”

The National Gallery is screening The Visit and a Secret Garden (2022) tomorrow, January 7, at 2 p.m.

Emily Wilson will be discussing her translation of the Iliad (2023) at Politics and Prose tomorrow, January 7, at 3 p.m.

Poem:

“The Trouble with the Times” by Thomas McGrath

In this town the shops are all the same:

Bread, bullets, the usual flowers

Are sold but no one—no one, no one

Has a shop for angels,No one sells orchid bread, no one

A silver bullet to kill a king.No one in this town has heard

Of fox-fire rosaries—instead

They have catechisms of filthy shirts,

And their god goes by on crutches

In the stench of exhaust fumes and dirty stories.No one is opening—even on credit—

A shop for the replacement of lost years.

No one sells treasure maps. No one

Retails a poem at so much per love.No. It is necessary

To go down to the river where the bums at evening

Assemble their histories like canceled stamps.

There you may find, perhaps, the purple

Weather, for nothing; the blue

Apples, free; the reddest

Antelope, coming down to drink at the river,

Given away.

[This is from McGrath’s Figures from a Double World, his sixth collection. (It’s also in his Selected Poems: 1938—1988). Figures from a Double World was published in 1955, two years before McGrath began his most-acclaimed work, the long poem Letter to an Imaginary Friend. (A side note: one short biography I found of McGrath, written by the poet himself in the 60s, ended with the sentence He has the distinction of having made several of the better political blacklists.)

In this poem, there’s such a sharp tension introduced by the way the surrealist and strange imagery—orchid bread, fox-fire rosaries, alongside things like treasure maps and the purple / Weather—are pitted against the ordinary parts of the town’s life. But even the “ordinary” scenes, those that the speaker explains as real, rather than hypothetical, take a move towards the unreal in the middle of the poem, when we arrive at catechisms of filthy shirts. But that only serves to increase the tension McGrath is unfolding in the poem, between what is (bread, bullets, the ordinary flowers) and what the speaker imagines as possibilities for this town.

I love what happens structurally in this poem to bring us to the ending. After the first stanza, every subsequent stanza begins with No: No one . . . , No one . . . , No one. Then, in the final stanza, there’s a continuation of this pattern, but with a turn: No. It is necessary . . . . And then into that strange reconciliation of the messy real town where bums at evening / Assemble their histories like canceled stamps with the imagined images, which here are so vivid in their colors: blue / Apples and the reddest / Antelope. Unlike the rest of the poem, where the unreal things are imagined being sold, in this final scene they’re all free, Given away. Even this last stanza, though, is an imagining—There you may find, perhaps, the speaker says—though while the rest of the poem imagines that these things could one day come to exist, the last stanza makes way for a tentative possibility that what the speaker is pointing toward already exists. —Julia]

Upcoming book:

[On Wednesday we said that Great Expectations by Vinson Cunningham comes out on January 23; it actually comes out on March 12. We regret the error.]

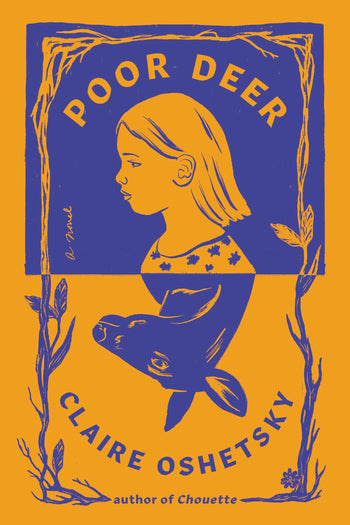

January 9 | Ecco

Poor Deer

by Claire Oshetsky

From the publisher: Margaret Murphy is a weaver of fantastic tales, growing up in a world where the truth is too much for one little girl to endure. Her first memory is of the day her friend Agnes died.

No one blames Margaret. Not in so many words. Her mother insists to everyone who will listen that her daughter never even left the house that day. Left alone to make sense of tragedy, Margaret wills herself to forget these unbearable memories, replacing them with imagined stories full of faith and magic—that always end happily.

Enter Poor Deer: a strange and formidable creature who winds her way uninvited into Margaret’s made-up tales. Poor Deer will not rest until Margaret faces the truth about her past and atones for her role in Agnes’s death.

Heartrending, hopeful, and boldly imagined, Poor Deer explores the journey toward understanding the children we once were and the stories we tell ourselves to make sense of life’s most difficult moments.

What we’re reading:

Chris read Lisel Mueller’s National Book Award winner from 1980, The Need to Hold Still. He reread the First Alcibiades. He is reading Persuasion and enjoying it thoroughly.

Steve read some more of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. He was also prompted by watching Broadway Danny Rose (1984) [An essential WRB text. —Steve] to investigate why the novelty Italian song—“That’s Amore,” things like that—is popular. [I still don’t get it. —Steve]

Julia read Olena Kalytiak Davis’ 2003 poetry collection Shattered Sonnets, Love Cards, and Other Off and Back Handed Importunities and Gillian Rose’s Love’s Work (1995).

Critical notes:

Wolfe would spend much of his career identifying and chronicling similar upheavals: the first astronauts, instant celebrities, leapfrogging fighter pilots in the status and honor hierarchy detailed in The Right Stuff; Junior Johnson and stock car racers cruising past a disapproving Southern gentry in public estimation in “The Last American Hero”; pop culture– and Pop Art–adjacent It Girls like Baby Jane Holzer toppling New York’s high society debutantes, as recounted in 1964’s “The Girl of the Year.” “Once it was power that created high style,” he wrote. “But now high styles come from low places, from people who have no power, who slink away from it, in fact, who are marginal, who carve out worlds for themselves in the nether depths, in tainted ‘undergrounds.’”

[Cf. Nick Burns’s piece on Wolfe, which we linked to on Wednesday.]

[I am once again tormented by the general reader here, the general reader who must be very slowly and carefully introduced to the notion that someone known for formal experimentation could be a conservative. Who wants to tell the general reader about T. S. Eliot?

As for Wolfe himself, both pieces take it for granted that everyone wishes for a Tom Wolfe for today, but I’m not convinced that this is so widespread. I associate this pining after Wolfe with an older generation. It’s not something I hear much of from people in their 20s. Maybe, like Burns writes, Wolfe helped contribute to his own obsolescence. Or maybe nothing can have that feeling of newness so important to the New Journalism so long after it was written, in the same way that Citizen Kane (1942) and Breathless (1960) no longer feel new—how could they, when everyone knows them and has been influenced by their once-novelties for decades? I don’t think it’s intrinsic to Tom Wolfe the man, not when there was a similar age split more recently in the feelings people expressed about P. J. O’Rourke when he died. People demand more of what they find vital; exciting curiosities from the past they can take or leave.Disclaimer: I was born in 1999. —Steve]