WRB—July 5, 2025

“unloved artisans”

This is not a British newsletter. It’s an American newsletter.

Links:

In Engelsberg Ideas, Ioannes Chountis de Fabbri on Nietzsche’s approach to reading:

From this arises a second axiom: proper reading stands in quiet defiance of the prevailing spirit of modern work and culture, which prizes speed, efficiency, and superficial grasp. The essence of philology lies not merely in resisting the times, but in seeking to shape them, to insist upon the value of reflection and precision for the sake of an age yet to come. It was this ambition that Wilamowitz described as Nietzsche’s “philology of the future”: the belief that, above all, to read properly is to read slowly.

Yet, slowness alone does not suffice. Nietzsche also insisted on the quality of engagement. To read well, one must be active rather than passive: reading is not consumption but confrontation. He draws a sharp contrast between those who savor and wrestle with a text, and those he derides as “reading idlers”: plunderers who strip works for slogans, then abandon the rest in confusion. In Human, All Too Human, he likens such readers to looting soldiers. By contract, the disciplined reader is likened to a kind of spiritual goldsmith, patiently refining insight through the crucible of difficulty.

Neil Postman:

A written sentence calls upon its author to say something, upon its reader to know the import of what is said. And when an author and reader are struggling with semantic meaning, they are engaged in the most serious challenge to the intellect. This is especially the case with the act of reading, for authors are not always trustworthy. They lie, they become confused, they overgeneralize, they abuse logic and, sometimes, common sense. The reader must come armed, in a serious state of intellectual readiness. This is not easy because he comes to the text alone. In reading, one’s responses are isolated, one’s intellect thrown back on its own resources. To be confronted by the cold abstractions of printed sentences is to look upon language bare, without the assistance of either beauty or community. Thus, reading is by its nature a serious business. It is also, of course, an essentially rational activity.

[While tracking down this quote in Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985) I encountered Postman saying that about four hundred thousand copies of Common Sense were sold in a colonial population of about three million. This is the same, proportionally, as a book selling 45 million copies in the current American population of around 340 million. Happy Fourth!

(Personally, I think the WRB should have 45 million subscribers. I’d like to write this newsletter on a boat.) —Steve]

In Liberties, Jenny Bhatt on van Gogh’s translations:

While copying the works of established, renowned masters was a common, lifelong learning practice for many artists, van Gogh did not simply copy. Instead, he intentionally experimented heavily with more interplays of color and light than in the original works. He discussed this in one of his 182 letters that referenced Millet. Sent from the asylum in January 1890, it is an eloquent, touching letter overall because he also refers to his “insanity,” his health concerns, being locked in, etc.: “So, working either on [Millet’s] drawings or the wood engravings, it’s not copying pure and simple that one would be doing. It is, rather, translating into another language, the one of colors, the impressions of chiaroscuro and white and black.” In undertaking such experimental translation, as with this particular painting, van Gogh created a bridge between the languages of Realism and Impressionism in specific ways that elevated the originals while advancing his own art.

[This method of study is certainly an improvement on the usual writerly “imitate Hemingway or whoever,” let alone “copy an existing text out by hand” (although I have done both and found both useful). But I couldn’t recommend it; pure imitation is hard enough. If van Gogh was capable of imitating and then tweaking to fit his own interests, that speaks more to his own genius than the merits of the practice. —Steve]

In UnHerd, Daniel Kalder on Black Sabbath:

Contemporaries like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple played heavy riffs but their ethos was hard rock, steroidal blues, even R&B, with (in the instance of Zeppelin) a whiff of Tolkien. Sabbath’s mutant blues, with its themes of angst, doom and horror, came straight from the depths of the abyss. Their streak of memorable riffs was unparalleled: applied to their music, terms like “sludge” and “grinding” became superlatives. Their influence spread. Judas Priest added another guitar and shrieked higher. Lemmy left space rockers Hawkwind to form Motörhead, turned up the bass and played faster. In Britain, in Europe, in America, in Asia, countless bands discovered endless possibilities within Sabbath’s elemental sound. Play louder, thrashier, slower; sing in a falsetto, sing like Cookie Monster; add blast beats; turn the riff into a drone; play in complex time signatures. Actually take the Satan stuff seriously, set fire to churches, murder your bandmates.

Yet, for all the variations of metal that exist today, no one has surpassed the work of the originators. While their heirs burrow ever deeper into narrower, more niche sounds, Black Sabbath were always looking outwards. They were fans of The Beatles, of blues and jazz; Iommi loved classical music and strove to bring its “tension and drama” to rock. Bill Ward made their songs swing, while Geezer found the groove in even Iommi’s heaviest riffs.

[There’s an interview with Geezer Butler where he explains that the riff in “Black Sabbath” came about because he was goofing around with Holst’s “Mars” and then Iommi tweaked it. (A version of “Mars” was also a centerpiece of King Crimson’s live show at the time; what was in the water in the UK then?)

And the idea that this kind of music could come “from the depth of the abyss” is not something original to Black Sabbath but something they got from the sources. In Robert Johnson’s Faustian “Cross Road Blues” (later covered by Cream and Skynyrd, among others) he reports “Lord, that I’m standin’ at the crossroad, babe / I believe I’m sinkin’ down,” and in “It’s Nobody’s Fault But Mine” (later covered by Nina Simone and Led Zeppelin, among others) Blind Willie Johnson explains that “if I don’t read, my soul’ll be lost.”

(Talk about the importance of reading—I don’t think Blind Willie Johnson was familiar with the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s Old Deluder Satan Law of 1647, which mandated that any town with more than fifty householders have a teacher since “one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, [was] to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures,” but he understood the spirit.) —Steve]

Reviews:

Two in the TLS:

Benjamin Markovits reviews two books about ideas in novels (The Possibility of Literature: The Novel and the Politics of Form, by Peter Boxall, 2024; and The British Novel of Ideas: George Eliot to Zadie Smith, edited by Rachel Potter and Matthew Taunton, 2024):

Other figures in the debate are the novelist Mary McCarthy, who wrote a polemic called Ideas and the Novel (1980), which made “a sustained and positive case for the novel of ideas,” and Sianne Ngai, whose Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (2020) seems to have been a catalyst for the present book. The point of it is both to revive certain novelists of ideas who might have been unfairly neglected, such as George Gissing and Katharine Burdekin, but also to revise our views of other novelists, like Ian McEwan and E. M. Forster (in a standout essay by Janice Ho), who seem to be doing fine—to consider them as novelists of ideas. The trouble is that, after a while, the lines start to blur. Ngai “identifies three gimmicky techniques in the novel of ideas: allegory, narrator discourse about ideas, and character debate.” But various critics expand the terms to include metatextual novels, political thrillers, comic novels and any novel with an argument to make, such as The Power and the Glory (1940)—“the only novel,” Graham Greene once said, “I have written to a thesis.” By the end I was a little puzzled to imagine what a novel without ideas would look like, as David Dwan admits in his excellent chapter on Iris Murdoch: “All novels are condemned to be novels of ideas on some rudimentary level.”

[Markovits quotes T. S. Eliot’s line about Henry James—“a mind so fine that no idea could violate it”— but show me the novel so fine that no idea could violate it. And if any of the people who complain about “novels of ideas” can produce a novel of no ideas I’d like to see that too. —Steve]

Daniel Wakelin reviews a new edition of Chaucer (The Oxford Chaucer, Volumes 1 and 2, edited by James Simpson and Christopher Cannon, 2024):

But that syncopated line invites the question: did Chaucer really always write ten syllables? The editors of The Oxford Chaucer, following the best metrical theory, argue assuredly that he did. First, they assert that Chaucer sounded or silenced the final “e”—that relic from Old English—as he wished, following not grammatical rules, but metrical ones. Second, they explain that, for this edition, they never rely entirely on a single scribal copy, prefer not to list the variants in all manuscripts, and sometimes emend the text based on their critical sense of metrical consistency. Such critical editing has long precedents, and thirty years ago would have looked dully traditional. But recent medievalists have, in a zeal for authentic voices, unloved artisans or visual culture, given primacy to the “material text” of manuscripts and the scribes who made them. Against that tendency, this edition is somewhat radical. The editors do discuss material books in their notes, but in line after line they adjust to seek the immaterial poem behind these books, the sound of air ybroken. I am not averse to this choice. It is what the scribes themselves sometimes tried to do—when they found that rhymes or stanzas in the exemplars from which they copied their texts did not work, some tried to guess corrections, albeit less often for the meter—and it makes this edition enjoyable. But it is a choice: The Oxford Chaucer is for hunters of poetry who would “scan the paces of a hare,” as Sir Ralph the priest put it, rather than pursuers of history from manuscript traces.

[In Aristotle’s De Anima, the air is continuous: “What has the power of producing sound is what has the power of setting in movement a single mass of air which is continuous from the impinging body up to the organ of hearing.” “Ybroken” is much more poetic, reflecting a poet’s attention to the differences and the breaks in sound. —Steve]

Two in our sister publication on the Hudson:

Lola Seaton reviews Sheila Heti’s latest (Alphabetical Diaries, 2024) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Jan. 20, 2024; we linked to an earlier review in WRB—Jan. 27, 2024.]

One of the less conspicuous tactics she uses to make her sentences distinctive is the conjunction “and”: “I was lying on the floor and I called him over and he got down on the floor with me and I was stroking his arm.” “And” refuses to specify the connection between each clause, meaning that Heti’s sentences flatten and spread out, acquire a deadpan poise, or sound a little starry-eyed. The voice of the child is rarely far away: “Nobody knows why marriages happen”; “All the really great things that have been created in art have been created by adults.” Heti also channels the voice of the child through repetition: “That night we dressed for dinner, and there was dinner”; “There was salt on my lips, and when I licked them, they tasted salty.”

What’s remarkable is that none of this feels affected or self-regarding. Just as Sheila can’t say why she is so moved by Manet’s paintings (the “something in his hand or his soul—or elsewhere”), it can be difficult to explain why Heti is a convincing writer. (As Heti herself complains in Alphabetical Diaries, “I am trying to learn from the Helen DeWitt book, but what is there to learn except that it works?”) For Heti, conviction is all that matters in art, and maybe she pulls off even her cheesiest adages—“Money always comes; it comes when you are true”—not because we believe the inanity, or even believe that Heti really believes it, but because we believe that she felt that way when she wrote it down, or perhaps we simply enjoy the sound of her confident, faintly humorous lyricism.

[“You don’t see so many ants as an adult”—speak for yourself. There are still plenty of ants walking around on the ground; your eyes are just further away. Look down and they’re still there. —Steve]

Anahid Nersessian reviews John Tottenham’s debut novel (Service, May):

A smile, a friendly greeting, a courteous and helpful demeanor—these are the requisites of service work, and they are precisely what Sean is incapable of providing. Service opens by dropping us into one of his shifts at Mute Books, where he is both pestered and boorishly ignored by customers who are too busy texting to answer questions like “Do you need a bag?” One, who comes in to purchase Kafka’s The Trial, brags “I exclusively buy books from shops like this and have been doing so for five years.” A woman whose manner suggests “an irony-free zone, a black hole of positivity,” won’t leave until she has forced Sean to mirror her artificial friendliness. “How’s your night going?” she asks. “Her tone,” Sean observes, “is as aggressively bright as her dyed hair, while her fake gratitude is a patronizing condescension to my distaste for the exchange.”

[We linked to an earlier review in WRB—June 14, 2025.]

In the local Post, Morten Høi Jensen reviews a new translation of a novel by António Lobo Antunes (Midnight Is Not in Everyone’s Reach, by Antonio Lobo Antunes, 2012, translated from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Lowe, June):

Over nearly 575 pages, this relentless probing of memory also demonstrates something of its desperate futility. Powerless to change the past, the narrator doubts and ponders, argues and accuses, remembers insults and settles scores: “What have I done?”; “why do people grow apart”; “you were the one who killed him, mother”; “where did you go, all of you.” And to what end? Only to long for “peace, and a ceiling of ocean in which the waves move without hurting.”

Antunes’ prose, viscous, metaphorical and baroque in his earlier novels, is made here of a more tentative, airier substance, filled with the surges, flickers and confusions of consciousness: “Death, I’m not afraid of dying, I’m only afraid of suffering, of pain, what a lie, I’m afraid of the Alto da Vigia, and my body, my body falling and not of suffering or pain, it’s death that terrifies me, no older brother waiting for me in the water, I helpless and nevertheless I have to do it not for my older brother, for me.”

[That bold initial statement about death that immediately gets pulled back into something revealing reminds me of the dream Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) has in The Conversation (1974): “I’m not afraid of death. I am afraid of murder.” —Steve]

N.B.:

The Journal has a list of “10 Masterpieces to Celebrate This 4th of July Weekend.” [Where’s the Whitman? (“We have one sap and one root— / Let there be commerce between us.”) Where’s Dylan informing the Brits, in between the angriest and best rock music ever made, that “this is not British music. It’s American music”? Good to see John Philip Sousa get a mention, though. —Steve]

[And why, on this weekend, is the Times publishing pieces that refer to “WAGs”? Whatever happened to republican simplicity? —Steve]

More Substack discourse, for those who like that sort of thing.

North Korea is opening a seaside resort.

New sentences in human history: “Everyone was driving their Range Rovers, staying in $100,000 rentals and eating cold cuts.” [No information on which cold cuts, alas; you can learn a lot about a person from that. —Steve]

A history of shorts.

A history of shoes.

A history of turbans.

Poem:

“Séance in Daylight” by Yuki Tanaka

She opened her mouth as if her throat were a bird

ready to leave her. I thought she was going to sing

for the dead, because she said she always saw them.

I was cold. I snuggled against her like a tall cat.

When she put the petals of a hydrangea on my eyelids,

I heard rain pattering behind them,

and I was a window from which she saw her friends

return: lights lit inside them, now alive, now burning,

moths in a struggle to escape their own wings

edged with fire. She waved at them and spoke

through me, fogging my skin with words I couldn’t hear.

I wasn’t cold anymore, her breath so warm, her cheek

pressed against the fragile glass, which was my body.

[I loved this poem from its opening line. “She opened her mouth as if her throat were a bird / ready to leave her”! It is familiar, maybe even a little cliché, to conflate birds with the throat, but Tanaka’s image—of its departure—is something new. This poem also represents the completed pivot, in the series of poems I’ve chosen, to contemplation of the body. Here, the author’s body is a transistor for the dead. His petaled eyes cannot see. Instead, his companion sees through him, her departed friends reanimated with “lights lit inside them, now alive, now burning / moths in a struggle to escape their own wings / edged with fire.” Haunting and grotesque, but also extraordinary in their beauty. Like Hebert’s poem, and also Hofmann’s, this poem dwells on an embrace. The author’s body is returned to materiality by his companion’s breath, fogging up and warming, reentering the land of the living. —K. T.]

Upcoming books:

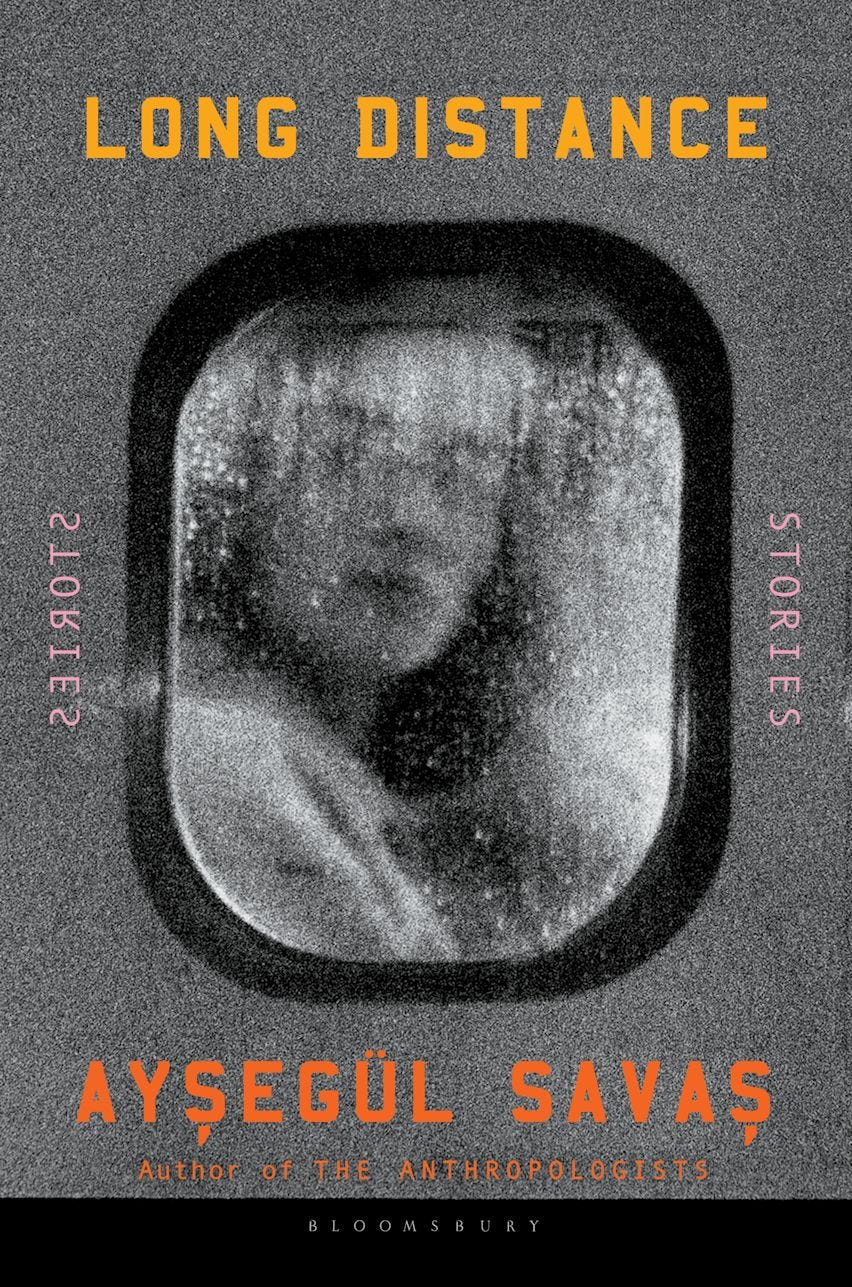

Bloomsbury | July 8

Long Distance: Stories

by Ayşegül Savaş

From the publisher: A researcher abroad in Rome eagerly awaits a visit from her long-distance lover, only to find he is not the same man she remembers. An expat meets a childhood friend on a layover and is dismayed by her unexpected contentment. A newly pregnant woman considers the American taboo of sharing the news too soon, but can’t resist when an opportunity comes to patch up a damaged friendship.

Long Distance showcases Savaş’ devastating talent for the short story. Her shrewd encapsulations of contemporary life often center on characters displaced more by choice than circumstance, characters both determined to install themselves in new lives and preoccupied with the people they've left behind.

Out tomorrow:

Seagull Books: Writings on Translation by Abdessalam Benabdelali, translated from the Arabic by Marouane Zakhir and Christian Hawkey

Also out Tuesday:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: The Other Love: Poems by Henri Cole

New Directions: Killing Stella by Marlen Haushofer, translated from the German by Shaun Whiteside [We linked to a review in WRB—June 28, 2024.]

Princeton University Press: The Key to Everything: May Swenson, A Writer’s Life by Margaret A. Brucia

Random House: Vera, or Faith: A Novel by Gary Shteyngart

What we’re reading:

Steve is still reading J R by William Gaddis (1975).

Critical notes:

Adam Roberts on memory:

The real message of “Funes the Memorious” is not that a complete memory would render life unlivable (lying in a darkened room, taking a whole day to remember a previous day in every detail, dying young and so on). The real message is: a perfect memory would be transcendent. It would enable us to recall not just the things that had happened to us, but the things that happened to everyone and everything with which we came into contact. This, of course, has no brain-physiological verisimilitude, but it speaks to a deeper sense of the potency of memory. In memory we construct another world that goes beyond our world. Imagination can do this too, but for many people imagination is weaker than memory; or perhaps it would be more accurate to say, imagination manifests itself most powerfully in memory, in the buried processes of selection and augmentation. Not for nothing do we dignify processes of recollection beyond the simplest as memory palaces.