WRB—June 15, 2024

’Sletter most foul

Next I was put to school to read the Washington Review of Books, in which I (poor wretch) knew not what use there was; and yet, if idle in learning, I was beaten. For this was judged right by our forefathers; and many, passing the same course before us, framed for us weary paths, through which we were fain to pass; multiplying toil and grief upon the sons of Adam.

N.B.:

The next WRB x Liberties salon will take place tonight. If you would like to come discuss the topic “Propaganda: do you know it when you see it?” please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

In the Financial Times, John Phipps chases down a little red book [No, not that one. —Steve] handed down to the actor deemed the best Hamlet of his generation:

A particular challenge of playing the part, Jacobi told me, is delivering lines so famous they risk breaking the audience’s suspension of disbelief. In his production, the second act began with Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy. Unusually, it was played as a speech delivered to Ophelia, rather than on an empty stage. In Sydney, at the end of the tour, Jacobi was waiting nervously in the wings. “I thought, ‘This is probably the most famous line in all drama. What if I forgot it? What if I went on and my mind went blank?’ And I went on, and I started . . .

To be, or not to be, that is the question / Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune / Or—

Or—

Or—

Or—”

Blinded to the astonishment of a thousand spectators by the force of the footlights, Jacobi realized he’d dried. Dried completely. It wasn’t like he’d forgotten the words. It was like he’d never known them. An entire minute of silence passed, until he was audibly given his line by Ophelia. Somehow, he got through the performance and the rest of the run. Afterwards, Jacobi didn’t go on stage again for two years. When I mentioned the incident, his eyes turned tight and hooded. He asked to talk about something else. Sensing my cue, I returned to the red book.

In Lit Hub, Sarah Viren interviews Elisa Gabbert about her new essay collection (Any Person Is the Only Self, June 11) [An Upcoming book in WRB—June 8, 2024; we linked to a review in WRB—June 1, 2024.]:

My essays often spawn other essays—I wonder if you find this too. There will be some aside or a tangent that I later go expand into an essay. (I sometimes think essays are merely excuses for asides.) Anyway, I did later write a whole piece about the architecture of essays. I have this theory that essays need both structure and mood. Some essays have rigidity of structure and not enough mood; some essays are all mood in shapeless space. Great essays have both. And architecture offers a really useful model for understanding the difference. You wouldn’t want an essay to feel like a newly constructed house with no furniture in it.

But you also wouldn’t want, or I wouldn’t want, an essay to feel like a half deflated bouncy house, or a party in a giant warehouse with too many smoke machines. I want some mystery and chaos, but the essay should have the capacity to lead me somewhere. The structure of the essay provides the walls or doors or passageways that let the reader feel change, change of mindset or change of mood.

Reviews:

Two in our sister publication across the pond:

Ange Mlinko reviews Rachel Cusk’s new novel (Parade, June 18) [The Upcoming book in WRB—June 12, 2024.]:

It’s clear that in contrast to G (Bourgeois), who was as good and bad “as any man,” G (Rohmer) is as good and bad as any woman, a prophet of male femininity like Rilke, who wrote to his friend Franz Xaver Kappus that “in the man, too, there is motherhood . . . physical and mental; his engendering is also a kind of birthing when he creates out of his innermost fullness.” G’s films, which are slow and repetitive, observant and true, are also gentle. They may well be the best illustrations of Rilke’s promise in the same letter to Kappus that “man and maiden, freed of all false feelings and aversions, will seek each other not as opposites but as siblings and neighbors and will join forces as human beings in order to bear in common, simply, earnestly, and patiently, the difficult sex that has been laid upon them.” G’s films are so true that they can only be filmed at the pace of real life, with as little cutting or editing as he can possibly manage. “The thrift and simplicity of G’s method,” it turns out, leads to a body of work that “flowed quietly out into the world and seemed naturally to join the stream of life.” The book-length dialectic of Parade pivots from the idea that one shall know the truth by its violence—the coup de poing—to the idea of truth as patience, acceptance, close attention.

Diotima in the Symposium:

Those who are pregnant in the body only, betake themselves to women and beget children—this is the character of their love; their offspring, as they hope, will preserve their memory and giving them the blessedness and immortality which they desire in the future. But souls which are pregnant—for there certainly are men who are more creative in their souls than in their bodies—conceive that which is proper for the soul to conceive or contain. And what are these conceptions?—wisdom and virtue in general. And such creators are poets and all artists who are deserving of the name inventor.

Rohmer: “It isn’t that I like girls so much that I feel the girl that resides in every man. I feel it in me.”

Béatrice Romand on Rohmer:

He understands the kind of women he wants to understand. He does not try to understand women who don’t interest him—like everyone else. He does not deal with women who suffer a lot. The social life of women is very little remarked in the films of Rohmer.

[Even Jane Austen, as far as I can recall, never wrote a conversation at which no women were present. —Steve]

Ryan Gosling, asked what percent woman he was: “I’d say 49 percent, sometimes 47 percent, it depends on what day you catch me.”

Patricia Lockwood reviews a collection of stories by A. S. Byatt (Medusa’s Ankles: Selected Stories, 2022):

Desire, seemly and unseemly: of the icewoman in “Cold” to slosh and melt, the corner of a painting to come alive in “Christ in the House of Mary and Martha,” the woman at the salon to smash up her reflection in “Medusa’s Ankles”—of history to happen differently. The first story in the book, “The July Ghost,” broaches the loss of Byatt’s son—though shyly, sideways, at a strange angle. In a “precise conversational tone,” a bereaved landlady tells us: “The only thing I want, the only thing I want at all in this world, is to see that boy.” The body keeps waiting, she explains, for him to come home, listens for his sounds, awaits his imprint on the air in Chelsea colors. Hopeless desire, then, and what it would look like for it not to be hopeless. Byatt would not go so far in fiction as to have the ghost appear to the mother, who is insensible, frozen, incurably sane. But she can invent someone—a lodger—to whom the boy, blond and smiling, does appear. The boy can even have his own purposes, as he did in life. He isn’t going after a ball this time, he wants to be born again.

In our sister publication in the City of Angels, Charlie Taylor reviews a new translation of a recently discovered novella by Céline (War, translated by Charlotte Mandell, June 25):

In Céline’s uncensored account of the experience of war, he continually works against the expected clichés of military heroism. Ferdinand is a pathetic imitation of what France seeks to valorize—a cowardly, lying soldier who cares less about comradeship and patriotic commitment than about ensuring that his wounds are severe enough that he will not have to return to the front lines. But what begins as a feigned madness soon turns genuine, as the unrelenting noise of war in his head threatens to overwhelm him. One evening, a comrade from the hospital, Bébert, who has been pimping out his wife to English and Belgian soldiers, sits down at the piano and comically shouts that he will “sing for France. [ . . . ] you’ll never shut me up, you hear me?” He then proceeds, accompanied by Ferdinand, to deliver a haunting rendition of a patriotic song, an unnerving performance wrung from two wounded, deeply disillusioned soldiers.

[This is the plot of Hamlet. —Steve]

In the TLS, George Prochnik reviews a book about Freud’s attitude towards his own life and his influence (Mortal Secrets: Freud, Vienna, and the Discovery of the Modern Mind, by Frank Tallis, March):

Freud’s statement that “biographical truth does not exist, and if it did we could not use it,” might initially suggest the Saturnalia of unprintably scandalous thoughts and memories rampaging around people’s brains; but this censorious view would accord ill with Freud’s own published oeuvre and theoretical disposition. Perhaps, if we take him literally, we can instead surmise that Freud meant to highlight the fact that “biographical truth” would have to encompass the vast realm of the unconscious driving much of our behavior, which must be rendered conscious in the act of writing about it, thereby altering its properties, like a chemical substance undergoing metamorphosis on exposure to light. “The unconscious is the true psychical reality,” Freud wrote in The Interpretation of Dreams, “in its innermost nature it is as much unknown to us as the reality of the external world, and it is as incompletely presented by the data of consciousness as is the external world by the communications of our sense organs.”

In 4Columns, Brian Dillon reviews a biography of Alan Vega (Infinite Dreams: The Life of Alan Vega, by Laura Davis-Chanin and Liz Lamere, June 18):

During the imperial phase of punk and its button-down pal “new wave,” Suicide were as much reviled as revered. Support slots for major bands turned into riots, notably while opening for Elvis Costello, as well as a rain of lethal coins from Cars fans, and even one axe-throwing incident at a Clash concert in Scotland. Vega: “You fuckers have to live through us to get to the main band.” His onstage persona—chain-wielding, smashing himself in the face with his microphone, but suddenly as plaintive as Johnnie Ray—remains a mystery in Infinite Dreams. What kind of release or escape was involved? Early on, Vega was estranged from most of his family, who he was convinced had disowned the wayward artist he had become. He didn’t attend his parents’ funerals. By all the accounts of friends and collaborators, he was a kind and genial man with blue-collar enthusiasms (every type of sport, playing the horses and the lottery) who seems to have evaded the excess and chaos that overtook many comparable performers. But then, with Suicide, there is a voice filled with dreams and pain, harried by phantoms.

[“Poor old Johnnie Ray,” as the song goes, is an interesting connection to Lou Reed and his encyclopedic knowledge of ’50s pop. But it connects Vega even more to Morrissey, who like Vega was engaged in a kind of ’50s and ’60s revivalism when that music was out of fashion and whose attempts at fitting kitchen sink dramas into pop songs are not that far off in spirit from “Frankie Teardrop” (even if I like hearing the likes of “This Night Has Opened My Eyes” and “Jeane” and I never want to hear “Frankie Teardrop” again. It’s a great song; I’m scared of it.) —Steve]

In the local Post, Elizabeth Nelson reviews a biography of Joni Mitchell (Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell, by Ann Powers, June 11) [An Upcoming book in WRB—June 8, 2024.]:

The title of Ann Powers’ remarkably insightful new overview of Mitchell’s work, Traveling, comes from the opening lines of “All I Want,” the first song on Mitchell’s masterpiece Blue (1971), which depicts the joys and terrors of a generation whose postwar prosperity engendered unprecedented social and geographic mobility. Mitchell is perhaps the finest chronicler of what was gained and what was lost on those endless highway runs, and of the quivering tension in the discovery of oneself at the expense of deeper roots. Freedom’s just another word, when everything is lost.

Mitchell is an awe-inspiring figure in both achievement and reputation—among peers, perhaps only Bob Dylan is so universally revered—a circumstance that has understandably but meaningfully biased previous biographers who spoke at length with her. Early on in “Traveling,” Powers explains her decision to not personally engage with Mitchell as a kind of protective literary scheme. Powers, a longtime music writer, speaks from experience about the rock star/journalist dynamic, which can cut both ways: “I knew that even a little intimacy can create the desire for more.”

[It’s true: “Coyote” is a superior work to On the Road. More notes on road narrative below in Critical notes. —Steve]

N.B. (cont.):

Linen shirt reviews from One Thing. [Linen is back. And it’s angry. —Steve]

Anglo musicians loved falling in love with Françoise Hardy (R.I.P.).

Sometimes the people doing man on the street interviews don’t recognize celebrities. [I’ll always have a soft spot for Alvin Plantinga on a local news segment about air conditioning. “You gotta have a PhD in engineering just to use your thermostat,” he says. The caption describes him as a man whose “Air Conditioner Stopped Working.” —Steve]

The world of the Excel World Championship.

The “first modern war game.” [You read a sentence like “The game took weeks to play; during that time, all cats had to be banished from the house to prevent them from disrupting the game pieces” and you immediately know whether it’s for you or not. —Steve]

A history of the EP.

How to save books from flood damage.

Julianne Werlin on the economic situations from which authors emerge.

Some notes on independent publishers in Frieze.

Image is hiring an editor in chief.

Local:

Some D.C. bars are making “DIY Chartreuse.” [This is probably as close as you can get to practicing alchemy these days. —Steve]

Archeologists have found some bottles of fruit preserved at Mount Vernon while George Washington was alive.

The new regime at the local Post is considering an idea called “Local+,” which will charge extra for “premium local content.”

The National Gallery of Art will show Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat (2024), a documentary about the connection between jazz and American involvement in the DRC after its independence, followed by a conversation with Johan Grimonprez, its director, and Remi Grellety, its producer, today at 1 p.m.

Poem:

“To My Son Henry, Asleep in the Next Room” by Andrew Collard

Where the Lane Closed sign sits flashing night and day

before the window of a stranger’s house, this afternoonwe paused amid the smell of tar so you could watch the crews

repair the road, and as a Bobcat shoveled out excess soil,I supposed, to myself, whoever lived there must have adjusted

to the constant lights and rumbling like an eye does to a scratchacross a lens, to see around it. Maybe the sounds of work,

after a while, become a kind of song to sleep by, like the oneswe sing at bedtime to muffle the passing cars, our too-loud

neighbors, or the imposed silence of evening. Tonight,when our setlist of Beatles songs and lullabies ran dry, you asked

to talk some mo’, for me to tell you, again, about the timeI came across a train in flames in the desert night, every detail

witnessed from the window of my van, or about the highwayI used to drive in circles in your early days to calm you,

how I’d carry you gingerly through the doorway, up the stairs,and to your crib, then sit in the next room over listening

through the monitor, in case you cried out. Even now, as youlie sleeping through the wall, in the same room where you once

sweated out a fever under blankets, and against my shirt,where the rocking chair shrieks some nights beneath me

like a key against a fence, and other nights is soundless,I’m astonished at how awake I have become, at just how much

I can recall: the sidewalk of your first steps, unendedby the roots of maples. How you held to both my hands

and tumbled forward step by wobbly step, delighted in your ownability to make great lengths of pavement disappear beneath you.

The way your eyes would drift, as we walked along the street,toward the treetops, lost of the spell of the twisting branches,

and the way you reached out your hand as if to grasp them.

[This is from Collard’s debut collection Sprawl (2023). —Julia]

Upcoming books:

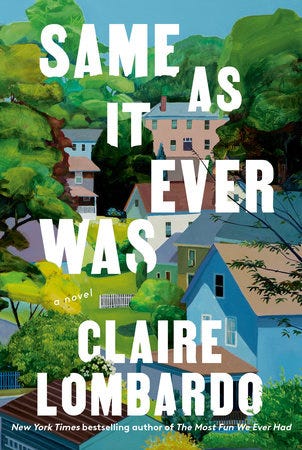

June 18 | Doubleday

Same As It Ever Was

by Claire Lombardo

From the publisher: Same As It Ever Was showcases the consummate style, signature wit, and profound emotional intelligence that made The Most Fun We Ever Had (2019) one of the most beloved novels of the past decade. Featuring a memorably messy family and the multifaceted marriage at its heart, Lombardo’s debut was dubbed “the literary love child of Jonathan Franzen and Anne Tyler” (The Guardian) and hailed as “ambitious and brilliantly written” (Washington Post). In this remarkable follow-up—another elegant and tumultuous story in the tradition of Elizabeth Strout, Ann Patchett, and Celeste Ng—Lombardo introduces us to an unforgettable cast of characters, this time by way of her singularly complicated protagonist.

Also out Tuesday:

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s by John Ganz

Harper: 1974: A Personal History by Francine Prose

Yale University Press: Spice: The 16th-Century Contest that Shaped the Modern World by Roger Crowley

What we’re reading:

Steve got riled up enough by something he read about parenting to get out Augustine’s Confessions and read the parts about babies and childhood; then he did the same thing after seeing Inside Out 2 (2024). [More on this in the next Film Supplement. —Steve] A friend of his was telling him about something she was working on related to the opening of Genesis, so he read Ratzinger’s “In the Beginning . . . ”: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall (1995). He also read Richard III. [One of Shakespeare’s funniest. Someone braver than I am should try to sustain a whole rom-com at the pitch of Richard’s wooing of Anne. —Steve]

Julia read about halfway through Elisa Gonzalez’s debut poetry collection Grand Tour (2023), then read more of Sigrid Undset’s Catherine of Siena and Scott Donaldson’s The Impossible Craft. She also spent some time with Larry Levis’ fifth collection The Widening Spell of the Leaves (1991).

Critical notes:

Vanessa Veselka on the absence of female road narratives:

During my travels I had literally thousands of interactions with people’s ideas about what I was doing with my life, but almost none of them allowed for the possibility of exploration, enlightenment, or destiny. Fate, yes. Destiny, no. I was either “lucky to be alive” or so abysmally stupid for hitchhiking in the first place that I deserved to be dead. And, while I may have been abysmally stupid, my choice to leave home and hitchhike was certainly no stupider or more dangerous than signing onto a whaling ship in the 1850s, “stealing” a slave and taking him across state lines, burning through relationships following some sketchy dude around the U.S., or accepting rides from drunk people while on hallucinogens. These tales are fictions, yes, but they deeply affect how we see people on the road. And the shadow cast by these narratives—one that valorizes existential curiosity, adventure, individuality, and surliness—does not fall over women. In a country with the richest road narratives in the modern world, women have none. Sure, there is the crazy she-murderer and the occasional Daisy Duke, but beyond that, zip.

[The road narrative has been a longstanding interest of mine—two of the very first books that made a deep impact on me were Jon Krakauer’s nonfiction book Into The Wild (1997), which follows the hitchhiking exploits and eventual death of ideal-driven twenty-four-year-old Chris McCandless, and Robert M. Pirsig’s autobiographical novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974). It’s been on my mind again after reading Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me (1966), which isn’t a road narrative per se but exists in the shadow of one; the novel starts when Gnossus, Fariña’s protagonist, returns to his campus after an extended journey across the US filled with close encounters with death. All three of these books are so different, but what binds them all is that the heroes’ travel is necessary for their intellectual or ideological work: they’re all in pursuit of authenticity (the American road narrative, particularly in the case of McCandless and Pirsig, is so indebted to Transcendentalism)—all of them are rebelling against the mainstream culture’s materialism, complacency, or conformity. Gnossus’ status as the rebellious, clear-eyed hero of the novel is confirmed by his ability to travel the country alone and get out of dangerous scrapes; McCandless abandons his car in a ditch, burns all his cash, and hitchhikes to Alaska to try to survive on his own; Pirsig’s protagonist gives his reader philosophical “Chautauqua” lectures in the midst of a seventeen-day cross-country motorcycle trip. Their travel proves their merit as heroes (for lack of a better term) and furthers their pursuit of their chosen virtues, but it also gives them the time and space to flesh out their philosophical visions.

It was only gradually, years after reading Into the Wild and Zen as a teenager, that I came to think of them as “masculine” books at all; for some time, the gendered nature of these narratives was a question that simply didn’t occur to me. And even once I’d realized it, I just didn’t really care. It wasn’t primarily the literal road trip that interested me. Back then (and, admittedly, now) what was significant for me about those books was the possibility of an unmediated experience of the American landscape and of a life built around pursuit of capital-t Truth—both of which seemed obviously gender-neutral endeavors, even if one didn’t die alone in Alaska in the attempt. But Veselka’s right in pointing out that these are narratives not afforded to women on the page, and that matters—especially because, as the books I’ve mentioned all suggest, the road narrative elevates the protagonist into a hero. They show that for a person to set out on his own, in order to pursue his intellectual and spiritual work in solitude, is an endeavor of substantial dignity and importance. The dearth of female road narratives raises the question: can we—do we—believe that’s true about as true about a woman as it is about a man? —Julia]

Naomi Kanakia on reading the Great Books:

How can anyone not want to read Anna Karenina? That original yearning, which is often weak and obscure, is quite frequently confused with a social yearning (the desire to be the kind of person who’s read Anna Karenina). And I don’t think the social yearning is invalid either! When society pushes people to do things that are good, then that's a good thing! We should be a society where having read Anna Karenina is a mark of distinction, and it’s a testament to the health of bourgeois society that there is such a strong cachet to being cultured. It’s actually kind of sick and disgusting when literary people—whose entire value is built upon a reverence for culture—start to deny or twist or turn upon people’s natural reverence for what is old and distinguished. But here’s the thing—you also can’t construct that reverence. People revere the Great Books (even if they haven’t read them) because they see that expert opinion for the Great Books is natural and unforced. We aren’t required to say we love Tolstoy. If anyone could seriously claim that Tolstoy is flawed and poorly-written, they could certainly publish an essay on the topic and the essay would be read. There is simply no need to insist to the world that Tolstoy is excellent. He is. You can open the book and see that for yourself! And if you can’t see it, then after ten or twenty years of reading, you’ll come back to him and change your mind.

Zach Williams on the fate of the short story:

My point is that some of the most exciting work I’ve seen in recent years comes from people who are working in shorter forms to different ends. A lot of them are technically short-story collections, but they don’t really make aesthetic sense without one another. My sense of these books is that the stories were written very intentionally to be part of one work, and I think that makes so much sense in our present moment. I could say something banal about attention spans, but it’s more than that. There’s something about the form of short stories and life on the Internet, scrolling and clicking, and the basic hypertextual experience of navigating the Internet. A book can contain many different worlds, too, without staying too long in one place.

It’s a vital time for the form. It’s equipped to do something that the big novel can’t, and there are a lot of writers doing really good work. But I’m not that smart about the necessities of the marketplace. I don’t know enough about how publishing works.