WRB—June 5, 2024

Literary posters

The Washington Review of Books, in its latest installment, says . . . well, it says many things, but none of these, though I have just read them, do I clearly remember, nor am I sure that in the act of reading I understood any of them. That is the worst of these fashionable Managing Editors—or rather, the worst of me.

N.B.:

The next WRB x Liberties salon will take place on the evening of June 15th. If you would like to come discuss the topic “Propaganda: do you know it when you see it?” please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

In the Financial Times, Cordelia Jenkins leads a discussion with Brian Cox, Simon Russell Beale, Kathryn Hunter and Greg Hicks about playing Lear:

Hunter: Marcello [Magni, her husband] was the Fool in my first production in 1997. He died, I was in denial about it, while we were doing the Globe production in 2022. Afterwards, I had this kind of visitation about those “nevers.” There’s a strange thing in that last scene. Lear goes, “I know when one is dead and when one lives, she’s dead as earth.” She. And then he goes, “Cordelia?” Direct address. “Cordelia stay a little, what is’t thou sayest?” Direct address. And he keeps going back between “she” and “thou.” And then he goes, “Thou’lt come no more.” Not “she’ll come no more.” “Thou’lt come no more.” Thou.

And it’s almost like Cordelia goes “What, never?” That he’s explaining death to her. “You see how it is darling? You’re never coming back.” “Never?” he hears her ask. “No, never darling.” “What, never?” “No, never, darling.” I don’t know, it just flipped in my head that it’s his last ever story to his little girl. “You’re never, ever, ever coming back.”

Beale: Jonathan Miller once said that “to be, or not to be” is an impossible statement because we have absolutely no conception of the second half of that sentence. We can’t, as human beings, locate not being. And what you were saying just struck a chord about trying to define what “never” means. It’s almost impossible, isn’t it? So he needs five goes at it.

[I’m pretty sure the film that Hicks describes at one point and that Cox identifies as The African Queen (1951) is actually Fitzcarraldo (1982). Interesting juxtaposition, though. —Steve]

In The Yale Review, Lydia Davis on darkness:

I also thought more carefully, after that experience, about what darkness feels like. In describing deep darkness, I want to use words like velvet or soft or blanket. Is that because darkness conceals the edges of what we see in light? The room I am in, illuminated by daylight, has many edges in it—not only the hard edges of the furniture but also the softer borders of a rug or the lines where the walls meet each other and the ceiling. A forest, though it is, in season, full of soft-seeming foliage, is also striped by the vertical hard trunks of the trees. Even the vast, billowy body of water that is the ocean is defined by the straight edge of the horizon. Absolute, unbroken darkness feels like one massive, enveloping substance, though it is not a substance and is not palpable. It feels close to the face, right up against the face. We need some light—even the faintest light will do—to create a perception of dimensional space. When there is no light at all, I have no depth perception, and so the darkness seems to press up against me. When I look into the near-complete darkness in my darkened bedroom at night, I sometimes see stipples, or pixels, evenly spread through the space, overlaying the dim shapes of furniture and walls, and I think perhaps they are coming from my eyes themselves.

[If you haven’t made it out to a part of the world with minimal light pollution, you owe it to yourself to do so and look at the sky. Go canoe the Allagash. The stars are waiting for you. (So are the bugs.) —Steve]

In Orion, Lulu Miller on “an arithmetic of grief and memory”:

The creature ahead in the creek is a fawn. It is standing, alone, chest deep in the water, in front of a small wooden footbridge.

I am trying to stop the kayak but can find no way to do it silently. My son is pressed against my chest. We are all, all three of us animals, frozen. Except that my son and I are gliding, rather quickly, toward the fawn. If ever there’s a moment that won’t last, it’s this one.

I drink in its every white spot, the pinks of its swiveling ears. My brain flicks off a million questions: Where is its mother? Do deer swim? Would it allow us to touch it? Is this a miracle?

Zeno’s paradox, the most famous of his paradoxes anyway, says that if you try to reach the other side by always moving halfway from where you are standing you will never reach it. Half and half and half, getting infinitesimally closer . . . but never there.

This odd mathematical thought exercise has always struck me with frustration, a peak lack of satisfaction. Until today, five days after the tall nurse’s death. As we careen toward the fawn, I wonder if any passenger ever tried applying Zeno’s paradox to their journey across the River Styx.

[Approaching wild animals by water is, in my experience, either solemn or farcical; in either case, it affords plenty of time to think—especially if the experience of time slows. And something about the animal intelligence on the other end tends to prompt unfamiliar reflection. What is it like to be a fawn? —Steve]

[Behind the paywall: Julia on various translations of a letter from Heloise to Abelard, Steve invokes Zeno’s paradoxes again, Torah scrolls, Niebuhr, posters, The New Yorker’s cartoon caption contest, late antiquity, Anne Carson, Barbara Pym, and more links, reviews, news items, and commentary carefully selected for you, just like on Saturdays. If you like what you see, why not sign up for a paid subscription? The WRB is for you, and your support helps keep us going.]

In The Chronicle of Higher Education, Eric Bennett on the creation and history of creative nonfiction:

Since the early 2000s, the heart of the creative-writing discipline has been neither stylistic nor mythological. Gutkind has reacted by celebrating the revolution, bidding so long to prestige and howdy to inclusiveness, as if identity and genre were inseparable. D’Agata has raged against the loss, insisting that pure literature—the stuff that once upon a time was invented in repudiation of referentiality—could, in fact, conquer referentiality. Fiction and poetry were deposed, yes. But what if the essay could climb onto the empty throne? In short, both D’Agata and Gutkind have labored on behalf of keeping literature—and especially nonfiction—big in an age when it isn’t any longer. Complicating matters is that, for now, their efforts seem to be working.

In Plough, J. L. Wall on Torah scrolls, Talmud codices, and the effects of the technologies we use to read:

So it came to pass that in the Venetian workshop of a Christian printer, the Talmud became the apogee of the codex, the most significant example of its technological difference from the scroll (and, indeed, of the printed codex from the manuscript). Today, we still follow Bomberg’s imagining of what the printed page could be and do. The Mishna and Gemara appear at its center, a column of continuous conversation enveloped in a ring of commentary: Rashi in his place of distinction, at the upper left-hand portion of each page, in “Rashi script”—a font the great commentator never used, but which Bomberg chose to help visually distinguish portions of the page. Opposite him, the comments of the medieval French Tosafists, many Rashi’s own students. Jewish printers gradually corrected Bomberg’s textual errors and omissions, revising and adding commentaries to the pages. If you open a volume today, the page you look at will likely be a variation on the late nineteenth-century Vilna editions. Typesetters and the printing press reshaped the role of the codex in Judaism. Voices separated by thousands of years and miles greet each other on the page as if they have always been and always will be in conversation.

In the local Post, Viet Thanh Nguyen on the initial decade of the National Book Awards in the ’50s:

Umberto Eco’s notion of one’s library as inevitably being composed mostly of books one has not read may be helpful here. “It is foolish to think that you have to read all the books you buy,” Eco wrote, and we might approach lists of literary award winners and finalists in the same spirit: They are aspirational, a log of what we could be reading and might yet read. These lists also remind us that we are probably overlooking work today that will be considered important in the future. Countercultural writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs are still read, but they did not merit notice from the National Book Awards in the 1950s. Neither did Isaac Asimov (I, Robot, 1950) or Ray Bradbury (Fahrenheit 451, 1953), foundational authors working in a genre that literary purists might have been prone to look down on as lowbrow and minor then, but one that is more esteemed in our time.

Reviews:

In Providence, John Shelton reviews Alan Jacobs’ book on Christian intellectual responses to World War II (The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis, 2018):

Jacobs receives the germ of this critique from Auden. In a review of Niebuhr’s Christianity and Power Politics (1940), Auden expressed feeling “le[ft] a little uneasy . . . by Niebuhr. “The danger of being a professional exposer of the bogus [like Niebuhr] is that, encountering it so often, one may come in time to cease to believe in the reality it counterfeits.” Auden wonders, “Does he believe that the contemplative life is the highest and most exhausting of vocations, that the church is saved by the saints, or doesn’t he?” While Auden answers this question in the affirmative (noting that “Niebuhr suggests here and there that he would agree with me”), Jacobs is not so sure, returning to it once again at the book’s closing as a final judgment on the “different course” supposedly followed by Niebuhr.

Yet T. S. Eliot, one of Jacobs’ protagonists, would totally disagree with such harsh judgment of Niebuhr.

Shelton added additional notes on Niebuhr’s relationships with his contemporaries on his Substack.

Two in Literary Review:

Jason Goodwin reviews Alex Christofi’s book about Cyprus (Cypria: A Journey to the Heart of the Mediterranean, July 23):

Cypria is enlivened by a delightful cast, from the poet Rimbaud, who surprisingly helped to build Government Cottage, to Ronald Storrs, a tidy-minded colonial governor who in 1931 watched as the same building burned to the ground after efforts to improve the quality of British rule had foundered on the rock of pro-Greek obduracy. Christofi poignantly notes that the old diplomat’s collection of art and books—which included a first edition of Candide, two David Bomberg landscapes and Byzantine icons—vanished in the fire, along with his chances of promotion. Storrs had amassed these treasures legitimately, assisted, he sadly recalled, “by the cigars I never smoked, the drinks I never drank, and the cabs I never took.”

[This is how I feel when I work on the WRB. (In the interest of transparency: I sometimes have a drink while working on it Tuesday and Friday nights.) —Steve]

Sophie Mackintosh reviews Joyce Carol Oates’ latest (Butcher, May) [The Upcoming book in WRB—May 15, 2024.]:

The constant stream of revulsion can be hard to stomach, but you do acclimatize, in part because the writing faithfully mimics nineteenth-century texts. Littered with italics and euphemisms, it gives a sense of both authenticity and distance. The cures themselves are based on archaic real-life treatments for hysteria—whether they involve excising the “hysteric” womb, rest and force-feeding or bizarre forms of hydrotherapy. The awareness that the “factual” passages are really fictional is what keeps the novel from becoming too bleak. A kind of knowingness underpins these descriptions. Weir’s accounts of his activities, in particular, are archly self-aggrandizing. He’s sniffy about inferior physicians who use bloodletting as a cure for everything; a dead patient may be dead, but she is still “cured” of diarrhea through intense dehydration. Humor doesn’t get more macabre than this.

In The London Magazine, Louis Harnett O’Meara reviews a book about the creation of the literary poster (The Art of the Literary Poster, by Allison Rudnick, March) as well as an exhibit of literary posters at the Met:

For all its high-brow appeal, the American poster sustained some of the old French poster’s countercultural tone. Ernest Haskell produced a raft of posters for comic paper The New York World, and A. K. Moe a number for student humor magazine The Harvard Lampoon, marking the start of a long love affair between satirical publications and punchy graphic styles. Youths threw “poster and hashish” parties, and some even hosted gatherings in which guests were asked to “dress up” as people from posters, as you might dress up as a character from your favorite film at a fancy-dress party today. Many posters also kept up the Art Nouveau tradition of tasteful ribaldry: the archive showcases a number of scantily clad women, and even nudes at times, though never without a conveniently placed bush.

[Maybe we should get that WRB clothing line off the ground. —Steve]

N.B. (cont.):

“The Ken Jennings of The New Yorker caption contest” offers tips. [Some of our readers, I have no doubt, have devoted most of their lives to thinking up new captions for Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus. —Steve]

Bill Guan, the CFO of The Epoch Times, has been charged with participating in a scheme to launder $67 million. [Journalism is back, baby! It’s good again! —Steve]

The LOA is having a sale on boxed sets.

New issues:

The American Scholar Summer 2024

BOMB Summer 2024 sneak preview.

County Highway Vol. 1 Issue 6 | May-June 2024

Literary Review June 2024 [As linked to above.]

The Miami Native Issue II available for pre-order.

Plough No. 40 | Summer 2024 [As linked to above.]

Sociotype Journal Issue #3: “Home”

Local:

Emma Collins on “THE BEST STORE IN D.C.”

Some turnover and turmoil at the local Post.

Rhizome D.C. has bought a new location and will move next year.

Subscription packages for the 2024/2025 Washington Performing Arts season are now available.

The National Building Museum’s exhibit on brutalism is now open.

The Dumbarton Oaks exhibit about women in late antiquity closes June 9. [You could also, if you were interested in the subject and felt so inclined, just look around you. Late antiquity? We’re living in it. —Steve]

The Capitol Visitor Center will screen Join or Die (2023), a documentary about community and loneliness in America, followed by a discussion with Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and Senator Chris Murphy, on Tuesday, June 11 at 5 p.m.

Poem:

“Sea Sonnet” by Alice Oswald

A field, a sea-flower, three stones, a stile.

Not one thing close to another

throughout the year. The cliff’s uplifted lawns.

You and I walk light as wicker in virtual contact.Prepositions lie exposed. All along

the swimmer is deeper than the water.

I have looked under the wave,

I saw your body floating on the darkness.Oh time and water cannot touch.

Not touch. Only a blob far out,

your singularity and the sea’s

Inalienable currents flow at angles . . .and if I love you this is incidental

as on the sand one blue towel, one white towel.

[This poem is from Oswald’s Spacecraft Voyager 1: New and Selected Poems (2007). —Julia

Upcoming books:

June 11 | Knopf

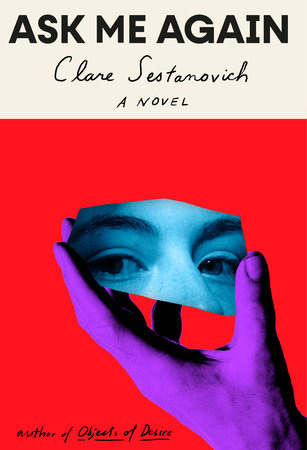

Ask Me Again

by Clare Sestanovich

From the Lit Hub preview: The two main characters in Ask Me Again are opposites: Eva is a middle-class achiever from south Brooklyn. Jamie is a wealthy Upper East Sider experimenting with political movements and spiritual quests. Previously, Sestanovich’s short story collection Objects of Desire (2021) was a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize.

The New Yorker has a recent essay from Sestanovich about related experiences in her own life.

What we’re reading:

Steve read more Beerbohm essays.

Julia read every English translation she could find of Heloise’s first extant letter to Peter Abelard. [I wanted to find the Latin of one specific passage, which in Betty Radice’s translation reads:

But you kept silent about most of my arguments for preferring love to wedlock and freedom to chains. God is my witness that if Augustus, Emperor of the whole world, thought fit to honor me with marriage and conferred all the earth on me to possess for ever, it would be dearer and more honorable to me to be called not his Empress but your whore.

I wasn’t able to find the letter in Latin online, so I ended up looking into older English translations of the passage. There’s a late eighteenth century translation by John Hughes, which reads:

But you have not added how often I have made protestations that it was infinitely preferable to me to live with Abelard as his mistress than with any other as empress of the world, and that I was more happy in obeying you, than I should have been in lawfully captivating the lord of the universe.

as well as a 1903 translation by Ralph Fletcher Seymore:

But you have not added how often I have protested that it was infinitely preferable to me to live with Abelard as his mistress than with any other as Empress of the World. I was more happy in obeying you than I should have been as lawful spouse of the King of the Earth.

The worst one, I think, was the 1925 translation by C. K. Scott Moncrieff:

I call God to witness, if Augustus, ruling over the whole world, were to deem me worthy of the honor of marriage, and to confirm the whole world to me, to be ruled by me forever, dearer to me and of greater dignity would it seem to be called thy strumpet than his empress.

But anyway, after all of that, I finally tracked down an answer to what I was wondering: Heloise tells Peter that she would rather be his meretrix—one of the two most common Latin words for prostitute, and the more neutral of the two—than be Augustus’ imperatrix. —Julia]

Critical notes:

Emily Wilson on Anne Carson:

In addition to ignoring literary history, Carson is uninterested in contemporary thinkers who might appear to have some insight into the nature of human desire. The first volume of Foucault’s History of Sexuality had been published in English by 1978—a vast and important project that was also obviously engaged with the topic of eros. But in her Eros, published nearly a decade later, Carson makes no mention of it. She also has little truck with psychology: When Carson comments that “infants begin to see by noticing the edges of things,” there are no footnotes; she feels no need to delve into the academic field of infant psychology to support her intuitions. Some readers, myself included, may also be conscious of the large gap between Carson’s literary abstractions and our own complicated experiences of desire and relationships with real-life human beings.

[The second piece about Anne Carson’s new book by a famous classicist to blunder by subjecting its readers to the definition and origin of the word “essay.” What’s going on here? (We also linked to other reviews in WRB—Feb. 7, 2024 and WRB—Apr. 24, 2024.)—Steve]

Sarah Ruden on Barbara Pym:

How does Pym make stories about pointless hopes, game disappointments, and dull resolutions so absorbing? Why is she not merely depressing, given that her likable characters appear as if at the bottom of a funnel of women’s literary history (Austen being the expansive top), where so little emotional room is left that even happy-ending marriages receive quite reserved coverage, careful qualification if they already exist, cool speculation if they are about to? . . . .

My guess is that the humanism of survival and small satisfactions is important here. Pym never married (though she put out with energy when she was young), and had a long, ill-used, underpaid career as assistant editor for the academic journal Africa. Diversions in her maturity included local church services and committee work. But she did not languish in boredom; she was so fascinated by mere people that she might shadow and research strangers until she could construct whole lives for them in her head. She could imply the workings of an entire household from a bunch of flowers or a chocolate biscuit. She never let go of the war’s being over, and tea and evensong still there. Perhaps that is as happy, and exciting, an ending as one can hope for at this point in history too.

Judith Shulevitz on Kafka:

The rabbis say that parables teach Torah. Jesus says that only the seeker for truth can understand parables. Kafka says no one can. It’s a strange claim for a storyteller to make. To what may Kafka’s pessimism be compared? To his parable “An Imperial Message.” A dying emperor entrusts a messenger with a message meant for you and you alone. The man is strong; he clears a path easily through the gathered throng. But the crowds and the courtyards multiply: “He is still pressing through the chambers of the innermost palace; never will he prevail; and were he to succeed at this, nothing would have been gained: he would have to fight his way down the steps; and were he to succeed at this, nothing would be gained.” And so it goes for thousands of years. And you? You “sit at your window and dream” of the message that never comes.

[Don’t we all sit at windows and dream of Zeno’s paradoxes? —Steve]