WRB—June 9, 2023

Circling back...

Outside are the big reviews of books, and sometimes the WRB succeeds in reflecting the big ones so that we understand them better. Or perhaps, we give the people who read our emails a chance to forget for a while, for a few short moments, the harsh world outside. Our newsletter is a little room of orderliness, routine, care and love. [I don’t know why I feel so comically solemn this morning. I can’t explain how I feel, so I’d best be brief. —Chris]

N.B.:

[Look. This was basically done at 9 am on Wednesday morning. But I had to get in a car and I hadn’t charged my laptop and no one else really did anything to get this over the finish line, so you’re getting it now, Friday morning, in place of both Wednesday and Saturday emails, since I’ve been able to sit down. I apologize for the interruption in service. —Chris]

Links:

Post45 has a new “cluster” dedicated to “Little Magazines”, edited by Nick Sturm.

Speaking of little magazines: in the Cleveland Review of Books, Yishai Jusidman has an essay about what “contemporary” means in the art world:

The massive avant-garde wave of the Sixties reignited the inventiveness, diversity, and group rivalries of pre-war modernists, with a notable exception: the political options available to an artist with avant-garde ambitions shrank to fit the prevalent countercultural protocols. Canny artists assumed the task of producing suitable material to stimulate the analytical faculties of progressive cultural critics, who would reciprocate by certifying in print the significance of those artists—setting into play an extended (and ongoing) exercise in symbiotic legitimization. Fittingly, Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes of 1964 inspired philosopher Arthur Danto to argue that artworks are best appreciated as “embodied meanings” waiting to be unpacked by an enlightened specialist.

Indeed, specialists engineered arguments to allow new art to pass political muster. While the chameleonic Warhol would be construed as a figure judgmental of consumer society, the Minimalists could be hailed as heirs to the Soviet Constructivists. Minimalism and Pop prospered by compounding coolness and criticality within the art market, by then well established, where the appropriate novelty produced commensurate profit. Artists with more uncompromising agendas turned to making art they trusted could not become merchandise—a concern common to Situationism, Fluxus, Concept Art, Performance, Body Art, and Land Art. Their creative activities needed to be provided for with income from sources other than the art market. This inconvenience would be mitigated once the social upheavals fizzled away and the cultural revolutionaries retreated to universities’ departments of the social sciences and humanities, spilling naturally into art schools, where they would welcome the institutional refuge and patronage while taking over the curricula.

The NYRB has Joshua Cohen’s introduction to New Directions’ new reissue of Croatian writer Miroslav Krleža’s On the Edge of Reason (1938, 1995, now out yesterday):

His was a laureled career in the only censorious, sometimes-Moscow-aligned-and-sometimes-not country where, if you had certain connections and ethnic protections, you could let your inmost imp speak. It was a mark of Krleža’s humanism that he understood this privilege as a responsibility to give voice to the imps of others—especially to those of his brother-writers being persecuted further east. The year On the Edge of Reason was published, 1938, was the final year of the Stalinist show trials and the year that Osip Mandelstam perished in the Gulag for the crime of writing a half-humorous poem that, basically, called the mustachioed Georgian who ran the USSR dumb and clumsy and fat.

Reviews:

Two in the LRB:

Emily Wilson reviews Epictetus (the new complete works out last fall):

Epictetus tells us a great deal about Achilles’ intense and—from a Stoic perspective—excessive suffering after the death of Patroclus, and suggests that such pain can be soothed only by a more rational attitude. He says nothing about the way egotistical rage and grief might be modified, as in the final books of the Iliad, through collective rituals of mourning and memorialisation, which can help us to understand and accept the inevitability of loss, and to abandon the fantasy of being all-powerful and entirely free from pain.

And James Butler on Italo Calvino:

Decaying language, political immobility, homogenised culture: Calvino’s world is also ours. But his sense of the problem is distinctive. He participated in a sharp discontinuity—the Resistance—that changed the future of his country. To experience a shift from historical agency to immobility is a special catastrophe. It is a necessary context for the somewhat barbed praise he gave in 1960 to a group of younger writers more theoretically adept than his cohort but for whom the link between ideology and human action was already dissolving: “For me, ideas have always had eyes, mouths, arms and legs. Political history for me is above all a history of human presences.”

Confidence that literary questions could bear large cultural and national significance was an enduring legacy of the postwar moment in Italy; it underpins even Calvino’s most abstract late meditations on semiosis.

Katy Waldman for The New Yorker reviews Dorothy Tse’s debut novel (Owlish, yesterday), out this week in translation from the Chinese by Natascha Bruce:

Amid all this, Q rebels by doubling down on fantasy. Aliss, he believes, has liberated his desires, imagination, and intellect. He grows his hair out and stops spending time at the university. He treats Aliss like a status symbol, whisking her onto helicopters and the balconies of luxury hotels. He hires a chauffeur to ferry the two of them around town in a minivan with tinted windows. “To hell with his university superiors!” he thinks. “To hell with his wife and her old, lowbrow friends! Fuck them all!”

But how free is he, really? Like Emma Bovary, he has escaped the prison of repression only to fall victim to his own mind. In his head, he is unbounded, a mythical figure, but from the outside Q resembles a “discarded toy,” full of “rusted gears” and “blocked-up pipes.” His dream woman, stranded between the organic and the mechanical, reflects his incomplete humanity—how he struggles to distinguish between freedom and ownership, how he can no longer conceive of what it would mean to be real.

In the local Post, Tim Parks reviews a recently translated Italian novel about finding your dad really annoying (The House on Via Gemito, 2020, May). Okay, but we’re paying attention because Domenico Starnone, the author, is supposedly Elena Ferrante. Anyway:

The novel gains with length. As drama and detail accumulate, we share the boy’s difficulty in finding a steady position vis-à-vis his father. Federico is the soul of every party, much loved, much hated, self-obsessed, hugely talented. Finally realizing that his wife is dying, he sketches her with pitiless accuracy, face puffy, gaze empty.

Starnone’s prose, ably and fluently translated by Oonagh Stransky, is compelling without being showy. He nails down his father in what could seem a tremendous act of revenge but is also a moving celebration of the man’s achievement and a profound consideration of artistic vocation. A final anecdote, recalling Federico and Rusinè in a playful tussle when the author was a child, is of such sublime ambiguity we wonder if we have understood anything at all about their marriage.

For the LARB, Ann Manov reviews a new collection of essays by Adam Shatz (Writers and Missionaries: Essays on the Radical Imagination, May):

The subject of his book is not “writers,” and not “missionaries”; instead, it is, he says, “portraits of writers, novelists, filmmakers, and philosophers of various commitments.” Even this might be misleading, I think—one would not, from that description, guess that Shatz has included such extraordinary essays on, say, Alain Robbe-Grillet or Jean-Pierre Melville. The subject of the book, or Shatz’s interest, one might say, is not so much politics or even the politics of art: it is the possibility of art within the human life.

Shatz is on the Selected Essays podcast from The Point this week talking about his book and James Baldwin’s essay “Alas, Poor Richard” (1961).

In Commonweal, Bailey Trela reviews Colm Tóibín (A Guest at the Feast, January):

There’s always been something clinical about the tone of Tóibín’s writing, a severity that insists on the raw accretion of facts. At its worst, this tendency can make his essays feel like little more than collections of quotations. Elsewhere, it provides a powerful charge. “A Brush with the Law,” which recounts Tóibín’s fascination with Ireland’s Supreme Court, is a case in point. The essay’s lengthy explanations of court cases dealing with homosexuality bear a clear edge. Tóibín’s real aim is to demonstrate how religious ideas get filtered through the legal system, how legal arguments against homosexuality are often just moral arguments in disguise. In a sense, his method elevates pedantry to a moral art.

N.B. (cont.):

N.B. follow ups:

On Saturday, we shared this Walrus piece about the state of media. Also in the new Commonweal, a review of Lance Morrow’s recent memoir (The Noise of Typewriters, March). And from Hamilton Nolan, “The Utopian Future Scenario of Media.”

[We also shared a FT puff about butter here. All well and good, but when I was discussing it with a friend later that morning, and we were affirming each other in our butter-buying habits (store brand for everything except schmearing, and always salted—there’s not so much salt in salted butter that you’re ever going to have an issue, except maybe making a frosting. Are you making frosting that often? Simplify your life, just buy salted butter!), I remembered something the piece said about Kerrygold: “the unsalted version, which is noticeably creamier than the salted.” (Emphasis added) This is obviously world-shaking information. Is this anyone else’s experience? Please let me know your butter takes. —Chris]

billy lennon (basic recon: June 2023) and Phil Christman (June–September 2023 Big Book Preview, Fall and Winter 2023 Big Book Preview) have new upcoming book picks up.

We would like to get out in front of things and acknowledge that no one associated with the WRB has ever met Tennessee Williams.

“A whole new online.” [Finally.] Here’s the Times profile. [We’ll see!]

Speaking of the Times, this is really scraping the bottom of the Didion content barrel.

University of Pennsylvania Press is having a 40% off sale through today.

Jewish Currents is hiring a fellow and an art director.

Issues we’re having:

The Drift’s Summer 2023 issue is coming soon.

And so is The Paris Review’s.

And so is The American Scholar’s.

The new issue of Genre is dedicated to the anniversary of John Guillory’s Cultural Capital.

Local:

“The bagels will be kettle-boiled, parbaked, and flash frozen at a new facility in Queens before being shipped in frozen trucks to the franchises, where they’ll be finished in special ovens.” [If that’s how you have to do it. —Chris]

The Capital Jewish Museum opens for the first time today.

U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy, M.D. (R-LA), announced that National Seersucker Day will be [was] held this year on Thursday, June 8. All senators are [were] invited for an official photograph at the Ohio Clock in the U.S. Capitol on Thursday, June 8, at 12:30 p.m. ET.

Also on the Hill: “Statue of renowned Nebraska author Willa Cather unveiled in U.S. Capitol”

Politics and Prose is having a Bloomsday event for your busy schedule. [yes I said yes I will Yes. —Nic]

There will be a launch reception for the new issue of Full Bleed on Thursday, June 22 at the MICA Store in Baltimore.

In the CityCast DC newsletter Wednesday morning, we read:

Learn the traditional Japanese art of Gyotaku, or fish rubbing, at the National History Museum for World Oceans Day. Unclear if live fish are involved

And, carjackings are up.

Upcoming books:

June 13 | Ecco

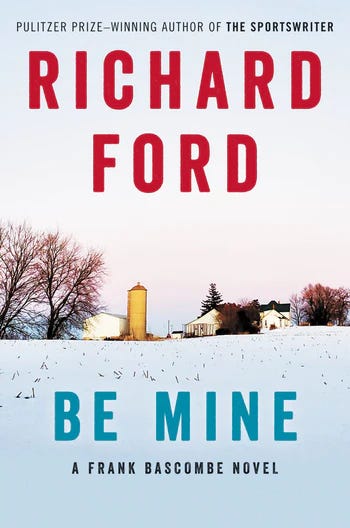

Be Mine: A Frank Bascombe Novel

by Richard Ford

From the publisher: Over the course of four celebrated works of fiction and almost forty years, Richard Ford has crafted an ambitious, incisive, and singular view of American life as lived. Unconstrained, astute, provocative, often laugh-out-loud funny, Frank Bascombe is once more our guide to the great American midway.

Now in the twilight of life, a man who has occupied many colorful lives—sportswriter, father, husband, ex-husband, friend, real estate agent—Bascombe finds himself in the most sorrowing role of all: caregiver to his son, Paul, diagnosed with ALS. On a shared winter odyssey to Mount Rushmore, Frank, in typical Bascombe fashion, faces down the mortality that is assured each of us, and in doing so confronts what happiness might signify at the end of days.

In this memorable novel, Richard Ford puts on displays the prose, wit, and intelligence that make him one of our most acclaimed living writers. Be Mine is a profound, funny, poignant love letter to our beleaguered world.

Here’s the Times review. [No better time to reread Joseph Bottum’s uncomplimentary assessment of Richard Ford in one of the early issues of The Weekly Standard: “A typical Ford tale is a sort of anti-picaresque ramble in which a man takes a short and boring trip for some poorly analyzed but usually mundane reason. Along the way, he has dozens of deep insights about cigarette lighters, suburban lawns, and the strangeness of ex-wives. Then something bad happens, usually something really bad, and the story ends with a last hopeful insight into the capacity of men with rich interior monologues to face a world in which really bad things happen.” —Nic] [I really did not like, or see the appeal of, The Sportswriter (1995). —Chris]