WRB—May 18, 2024

“a fairground wall of death”

Many a man lives a burden to the Earth; but the Washington Review of Books is the pretious life-blood of a master spirit, imbalm’d and treasur’d up on purpose to a life beyond life.

N.B.:

The next WRB x Liberties salon will take place tonight. If you would like to come discuss the topic “Should you like your friends?” please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

Two on Alice Munro:

In the Times, Sheila Heti:

She will always remain for me, and for many others, a model of that grave yet joyous dedication to art—a dedication that inevitably informs the most important choices the artist makes about how to support that life. Probably Ms. Munro would laugh at this; no one knows the compromises another makes, especially when that person is as private as she was and transforms her trials into fiction. Yet whatever the truth of her daily existence, she still shines as a symbol of artistic purity and care.

In The New Yorker, Deborah Treisman:

Munro was loyal to the short story. I remember her telling me once that she frequently believed she was embarked on a novel, only to find that the narrative ended after forty pages or so. Though she sometimes framed this as a failure, it was actually a reinvigoration of the form. Her stories were novels with the extra bits removed, no time wasted on the fallow or uneventful stretches. Fellow fiction writers often speak with awe about the movement through time in her stories—how she could focus tightly on one short period in a life and then abruptly leap years, or even decades, forward or backward, without breaking her narrative line. Her stories are like mountainous landscapes, with trails that wind gradually upward to dramatic peaks, spill down into valleys, and then climb again. As in life, what can seem to be the climax of a narrative is sometimes just a prelude to what comes next.

[From Franzen’s old Times essay on Munro: “Reading Munro puts me in that state of quiet reflection in which I think about my own life: about the decisions I've made, the things I've done and haven't done, the kind of person I am, the prospect of death. She is one of the handful of writers, some living, most dead, whom I have in mind when I say that fiction is my religion.” —Chris]

In the Literary Review of Canada, Robert Lewis on his time at Time in the ’60s and ’70s:

Memories of [Chappaquiddick] haunt Kennedy even during our bucolic campaign outing in 1970. As the day ends, traffic into Boston has slowed to a standstill. His driver, anxious to get to Logan Airport, eases the nondescript Impala sedan onto the shoulder of the highway, speeding around cars lined up bumper to bumper. From the back seat, the Washington Post veteran Jules Witcover chirps, “Can’t you just see the headline: ‘Kennedy in Car Crash.’” With that, the senator sits bolt upright from his reading and exclaims, “Joe, stop the car!”

Two or three nights later, there is a similar message—for me. I am sitting in the back seat with Edmund Muskie, the grumpy Democratic senator from Maine, trying to interview him about his own re-election bid as we speed along I‑95 in the dark. I am not allowed to take notes during our conversation. And then the car suddenly stops in the middle of nowhere—and I am ushered out and deposited into a trailing vehicle. End of interview. Like Kennedy, Muskie would be re‑elected handily in 1970, and I have disliked interviewing politicians in cars at night ever since.

[If I were a passenger in a car that suddenly stopped on 95, in the dark, in the middle of nowhere, Maine, I would start begging for my life. —Steve] [I’d start as soon as I realized I were in Maine. —Chris] [Guess you really hated the Moxie cocktail, huh. —Steve]

Two in our sister publication on the Hudson: first, Fintan O’Toole on Shakespeare’s tragedies:

So what does Shakespeare teach us? Nothing. His tragic theater is not a classroom. It is a fairground wall of death in which the characters are being pushed outward by the centrifugal force of the action but held in place by the friction of the language. It sucks us into its dizzying spin. What makes it particularly vertiginous is the way Shakespeare so often sets our moral impulses against our theatrical interests. Iago in Othello is perhaps the strongest example. Plays, for the audience, begin with utter ignorance. We need someone to draw us in, to tell us what is going on. A character who talks to us, who gives us confidential information, can earn our gratitude. Even when that character is, like Iago, telling us how he is going to destroy a good man, we are glad to see him whenever he appears. Within the plot he is a monster. Outside it, talking to us, he is a charming, helpful presence. Drawn between these two conditions, we are not learning something. We are in the dangerous condition of unlearning how we feel and think.

Reviews:

Second, Peter Brown reviews a history of one thousand years of Christianity (Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, AD 300–1300, by Peter Heather, April):

Let me make a suggestion: modern historiography of the expansion of the early Church seems to have left little room for the Holy Ghost. Don’t get me wrong: I do not speak as a theologian but as a historian. We should remember that the people we study lived in a world crowded with invisible beings. Some of these beings were demons driven by chill malevolence. We hear much about them in literature and in contemporary belief. But humans could also be touched by the warm presence of benevolent spirits, seen as ever ready to protect and to inspire individuals. We should not forget that even the classical Muses, outdated though they might appear, continued to be surrounded by a numinous aura. When the senator and poet Paulinus of Nola announced to Ausonius in the late fourth century that he had been converted to Christianity, it was enough for him to explain to his old mentor that he had found that the mighty wind of Christ blew into his heart with greater warmth than did the plump classical ladies still displayed on innumerable works of late Roman art.

[I support the use of “Holy Ghost.” —Steve] [A reader was just saying to me that he can’t stand the affectation—a sentiment which I understand of course—but I can’t really bring myself to mind it. To me it feels cozy to say. —Chris] [Some of us were raised on the KJV. —Steve]

In The Chronicle of Higher Education, Katie Kadue reviews an attempt to bring together Shakespeare and Freud (Second Chances: Shakespeare and Freud, by Stephen Greenblatt and Adam Phillips, May 14):

While Phillips’ retrospective mode is one of stylistic revision, Greenblatt’s is of vague musing about the rupture in his life that led to his own “second chance.” Lingering on “the scent of eucalyptus mingled with tear gas” as a metonym for the University of California at Berkeley campus, Greenblatt thinks back on the circumstances that led him to leave one prestigious university for another, one coastal city for another, one name (Steve) for another (the rather similar Stephen), one reading audience (scholarly) for another (popular), and one wife for another (a graduate student). “To what extent was this change of course a matter of chance, arbitrary, accidental, and unearned, and to what extent was I in control?” he asks as blandly as a product manager defending his rollout strategy. “What was I looking to gain, and what were the costs?” In Shakespeare, a second chance doesn’t usually look much like a job offer from Harvard, and when he offers a character a second life, it doesn’t usually come with a second, younger wife; for Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, as in the Shakespearean films that enchanted Cavell, it means ending back up with the same old wife, made new. (Phillips makes a similar elision, making Cavellian “remarriage”—which doesn’t have to be a marriage but does, crucially, have to involve the same person—sound as if it could refer to any “second marriage.”) With Freud peering over his glasses at us from Chapters 5 to 7, it’s hard not to wonder why Greenblatt is so insistent on putting his autobiography in conversation with Shakespeare’s plots, and yet so resistant to anything but a pat synopsis of his life’s pleasing symmetry.

[“What was I looking to gain, and what were the costs?” reminds me of a passage from Nic’s review of David Brooks’ most recent in The Lamp:

Why do this? I suspect one reason is that Brooks is growing old and looking back on his life with some regret. He has adult children and a second wife. He works in a world in which young upper-middle-class strivers classify him and other upper middle class Boomers in the most uncharitable ways. I imagine that, as Brooks begins to think about death, he finds that questions about what your refrigerator says about the average income in your zip code no longer seem all that pressing. Now the important questions are more like these: Have I lived well? Can I still live well? and, often, Why am I not happy?

If Greenblatt wants it framed as calculating benefits and costs, I would turn to a commentator whose words I value even more than Nic’s:

For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it?

Lest haply, after he hath laid the foundation, and is not able to finish it, all that behold it begin to mock him,

Saying, This man began to build, and was not able to finish.

But then this advice assumes you know (or think you know) what you want to do, and insists that you really think about what it requires of you. “Was I in control?”—in other words, “why am I here?”—is not really the question of a man who knows where he is, or why he is there. Nic’s review ends:

And is it not the tragedy of the Bobo that the project always ends the same way? The harder you try to build the life you want, the more trapped you become in a miserable class of your own design.

And the elisions Kadue identifies make second chances part of a project. They aren’t. They’re grace. Greenblatt thinks of them as something that just happens to you—“arbitrary, accidental, and unearned”—but that leaves no room for gratitude. It’s not the life you want; it’s the life you didn’t know you wanted, because you didn’t know you could have it. As Barbara Stanwyck says in The Lady Eve (1941):

If you waited for a man to propose to you from natural causes, you’d die of old maidenhood. That’s why I let you try my slippers on. And then I put my cheek against yours. And then I made you put your arms around me. And then I, I fell in love with you, which wasn’t in the cards.

You can make a project of it all you want, but if the second chance comes it won’t be concerned with the project. —Steve]

In The Hudson Review, Meg Schoerke reviews a new edition of Emily Dickinson’s letters (The Letters of Emily Dickinson, edited by Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell, April):

Styling poems—existing or new—as her “letters to the world” was not simply a metaphor, but common practice for Dickinson, and 214 of the “new” letters that Miller and Mitchell include in their volume are what they classify as “letter-poems”: poems that Dickinson addressed or signed to others. The inclusion of letter-poems makes the reading experience strikingly different for Miller and Mitchell’s edition than for Johnson and Ward’s edition, both as a reflection of what Dickinson actually sent to her correspondents and also giving readers a way of contextualizing some of the poems (which doesn’t preclude the option of reading them in other ways, such as part of a fascicle series), though the letter-poems nonetheless often resist biographical interpretation. For example, for 1864, Johnson and Ward include 14 letters. Adding letter-poems, Miller and Mitchell increase that number to 33. While a few of the letter-poems from 1864 reference the prospect of blindness and the difficulty of being away from home, the rest are not so limited to her immediate circumstances and vary in theme and tone, encompassing musings on self, nature, the soul, and the sheer awe of living and include poems that became among her best known.

[We linked to an earlier review in WRB—Apr. 13, 2024. The claim in this review that Thomas Johnson, in his edition of Dickinson’s letters from the 1950s, did not annotate a reference to “delenda est” to make Dickinson seem more apolitical ignores the more obvious explanation: he would have assumed his readers knew one of the most famous Latin phrases and its context and so felt no need to annotate it. (I’ve linked to them before a number of times, but BDM’s comments on what the general reader is assumed to know apply here as well.) —Steve]

Two in our sister publication on the Thames:

Irina Dumitrescu reviews a book on medieval entertainment (Minstrels and Minstrelsy in Late Medieval England, by Richard Rastall and Andrew Taylor, 2023):

Minstrels’ employers—royal households, noble families and religious institutions as well as towns—each had needs particular to their business. The queen would have lutenists play to her and her ladies, but had little use for loud minstrelsy; the king’s minstrels, by contrast, worked at the ceremonial events where it was required. Religious houses might have minstrels perform at a saint’s feast day, or play music for celebratory dances, such as the one that took place at St Paul’s Cathedral to mark the birth in 1312 of the future Edward III. There were other, highly specific functions. Records show that there was a common practice of minstrels performing in front of images of the Virgin in church, sometimes while nobles were giving alms. The king’s minstrels would play during meetings with visiting dignitaries, and Rastall suggests that one of their roles was to drown out the sound of private conversations at large events. When the king was traveling, minstrels signaled his location to the rest of the household, rather like a medieval tracking device. And in stressful situations, minstrels sometimes served by soothing their employers. In 1297, a harper called Meliorus was rewarded by Edward I for “making his minstrelsy before the king for several days at the time of the king’s bloodletting at Plumpton.” Another harper was paid in 1337 for spending time with Edward of Woodstock during a childhood illness.

[If you are a member of a royal family who would like to reward the Managing Editors of the WRB, please get in touch. —Steve] [Not to imply that the favor of some lower aristocrat would be beneath us! —Chris]

Adam Mars-Jones reviews Álvaro Enrigue’s latest novel (You Dreamed of Empires, 2022, translated by Natasha Wimmer, January):

In Enrigue’s Tenochtitlan there’s no shortage of subjectivity, and even an awareness of imminent collapse. Moctezuma’s paranoia had led him to mistrust the meritocratic administrative system, the very rough equivalent of a civil service, which he replaced with family members who were loyal to him. He withdrew from public life, apparently unconcerned that subjugated tribes were ready to revolt, and resorted more and more to hallucinogens. There’s plenty of black comedy in the inadequacy of his retinue’s efforts to address the crisis caused by the Spaniards’ arrival. Atotoxtli does what she can, though “hurrying didn’t mean canceling her afternoon bath, of course, just cutting it a little short.” The mayor attends a summit meeting, convened in the traditional manner, with equipals, chairs described as “uterine,” brought along for those attending (the Spaniards find their design strange since there is no way of hanging weapons on them). Before anything can be discussed, the Legend of the Five Suns, the cornerstone of Aztec cosmology, must be sung in full. It seems to take hours. The impression that time has slowed down or stopped is reinforced by the name of the functionary doing the recitation: He Who Looses the Rain of Words and Governs the Songs Lest We Be like the Flowers and Bees That Last but a Few Days. It may be that the mayor is being sent an urgent message in the absence of the emperor, but he can’t make it out. Nothing could make it clearer that this is an ancien régime, exquisitely calibrated internally but with no ability to mobilize when a novel danger presents itself.

In Jacobin, Alex N. Press reviews a history of The Village Voice (The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of The Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture, by Tricia Romano, February):

Cartoonist Jules Feiffer was a key early get. As Fancher tells it, Feiffer walked into the office in the paper’s first year “with a pile of cartoons under his arm.” No one else would publish them; did the Voice want them for nothing, with the caveat that they publish one every week? Yes, they did—the cartoons would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize. Stories of staffers getting jobs by simply showing up at the office with an idea abound.

Vivian Gornick recounts submitting a piece to Wolf about LeRoi Jones (later better known as Amiri Baraka) at the Village Vanguard, the legendary jazz club. Says Gornick: “A few days later, he called me up. ‘Who the hell are you? Send me anything you’re writing.’” So began her storied career. The Voice was a flame, and weirdos far and wide were inexorably drawn in.

[We linked to previous reviews in WRB—Feb. 14, 2024 and WRB—Feb. 24, 2024; I’d like to think the WRB is sort of like this, except I’ve never had an idea. —Steve] [The only idea I’ve ever had is the one for a Washington Review of Books. —Chris]

N.B. (cont.):

“The Babylonian Talmud recommended eating the outer leaves of the onion first, as the heart was thought to be the best part. It also states: ‘One should not eat an onion from the base but from the top, and anyone who does otherwise is a glutton.’” [Best to be safe about such things, at least. —Chris]

The life of a Scrabble obsessive: “This morning—before those nineteen games, the instant I woke up—I realized that the letters in CAUTIONED can be rearranged to spell EDUCATION.”

The Atlantic is hiring for a number of positions.

New issues:

The Hudson Review Spring 2024 (Volume LXXVII, No. 1) [As linked to above.] [I noticed this week that The Hudson Review is the highest-scoring periodical on the living room test. —Chris] [If only Paul Fussell were around to see the Washington Review of Books. —Steve]

Literary Review of Canada June 2024 [As linked to above.]

Polygraph Issue 29: Narrative and Crisis | Summer 2024 [As linked to below.]

The Spring 2024 issue of Boston Review is now available for pre-order.

Local:

A review of an exhibit of Japanese prints depicting supernatural presences in theater at the National Museum of Asian Art.

The Aaron Diehl Trio will perform an adaptation of Mary Lou Williams’ Zodiac Suite for chamber-jazz ensemble at the Lincoln Theatre tomorrow, May 19 at 7:30 p.m.

Politics and Prose will celebrate its 40th anniversary with a series of activities, including a panel discussion on the history and future of bookselling, on Saturday, June 22.

Fair warning: Bonnard’s Worlds closes at the Phillips in two weeks.

Poem:

“Too Bright To See” by Linda Gregg

Just before dark the light gets dark. Violet

where my hands pull weeds around the Solomon’s seals.

I see with difficulty what before was easy.

Perceive what I saw before

but with more tight effort. I am moon

to what I am doing and what I was.

It is a real beauty that I lived

and dreamed would be, now know

but never then. Can tell by looking hard,

feeling which is weed and what is form.

My hands are intermediary. Neither lover

nor liar. Sweet being, if you are anywhere that hears,

come quickly. I weep, face set, no tears, mouth open.

[This is the title poem of Gregg’s first poetry collection, published in 1981.

Last August, we featured another, later poem of Gregg’s. Since first reading that poem back in August, I’ve returned to it again and again. One thing I love so much about that one (that I see in today’s poem as well) is how straightforward the syntax is—clipped, almost—and how, at the same time, full of sureness and music the voice is. I love the simplicity that rings out in lines like

We lay on the grass in the dark and he placed

his hand on my stomach while the others

sang quietly. It was prodigious to know

his eagerness. It made me smile warmly.

and

. . . I was a secret

there because you were married. I am here

to tell you I did not mind. Existence

was more valuable than that.

They feel so close to the voice in “Too Bright to See”, although “Too Bright” is stranger at times—in small, wonderful moments: the light that gets dark in the first line; the fact that, here, weed and form are opposites; the sudden syntactic complexity of the sentence It is a real beauty that I loved / and dreamed would be, now know / but never then.

In terms of wonderful, strange moments that this poem has, it’s worth mentioning the metaphor in the line I am moon / to what I am doing and what I was. That line is not only beautiful, but is so central to this poem. We’re no longer just talking about the fading light of the garden, but the self. To be alive as a human is to change—whether we want to or not, whether we understand the change we’re undergoing or not—and I love how Gregg describes it in that line. Moon as in undergoing phases, constantly cycling. Moon as in eclipsing, eclipsed. As in reflecting the light from somewhere else; as in cratered, as in sometimes completely hidden. There are so many ways to read it, but it is, to me, ultimately about the ways we can become foreign to ourselves in the midst of our own change. But here, in Gregg’s musicality, we see that even in times when we are unknown to ourselves, there’s possibilities for beauty. And if surviving change (so to speak) comes through concentrated effort (tight effort, as Gregg says, an effort that occurs again later in the poem: looking hard), the beauty emerges only through acceptance of the changing self’s in-between-ness:

My hands are intermediary. Neither lover

nor liar.

But this poem doesn’t end with its focus still on the self, and I think that’s an important element here. Sweet being, if you are anywhere that hears, / come quickly. I love that line, with its sudden calling out to the beloved. Come quickly. There’s trust there, and hope, and yet it’s still marked by the uncertainty, and distance, that we see in the line about the moon: if you are anywhere that hears.

It’s a complex ending, those final two sentences. On first read, it’s sad, almost a defeat, with the weeping and the call to come quickly. But to me what’s important is the way that final sentence functions as a gesture of deep intimacy; the speaker describes the physical details of her weeping with a level of specificity you’d only really extend to a lover. As in: this is how I’m crying, I need you, come over. There’s so much trust in that, and even though there may be no way of knowing if the sweet being is within hearing distance, there’s the possibility that he is, and in the possibility there’s hope. —Julia]

Upcoming books:

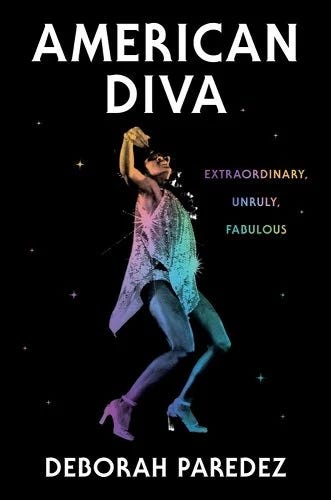

May 21 | W. W. Norton

American Diva: Extraordinary, Unruly, Fabulous

by Deborah Paredez

From the publisher: What does it mean to be a “diva”? A shifting, increasingly loaded term, it has been used to both deride and celebrate charismatic and unapologetically fierce performers like Aretha Franklin, Divine, and the women of Labelle. In this brilliant, powerful blend of incisive criticism and electric memoir, Deborah Paredez—scholar, cultural critic, and lifelong diva devotee—unravels our enduring fascination with these icons and explores how divas have challenged American ideas about feminism, performance, and freedom.

What we’re reading:

Steve was too busy getting ready to move to read anything. [Still got this newsletter out just for you, though. —Steve]

Julia was also moving this week, and also didn’t read much.

Chris, for the first time in quite a while, actually read a bit this week. After the WRB Presents reading on Tuesday, he read Joseph Grantham’s book (the one that’s still in print, Raking Leaves, 2019). [Joey’s poems are really funny—he had the whole room eating out of his hand on Tuesday night—but no matter how much I snorted invitingly while I was reading these no one in the room asked me to read them one out loud. A minor disappointment, to be sure. —Chris] He finished reading Ryan Ruby’s novel as well (The Zero and the One, 2017, not to be confused with a perhaps more well-known work), which actually managed to take him totally by surprise, plot-revelation wise, several times in the final stretch. He started listening to another Jane Austen on audiobook (Sense and Sensibility). [I’ve been working through Austen slowly—this has been for all of nearly half-through 2024—and out of order—I’m saving Pride and Prejudice and Emma until last. I initially loathed, readers may recall, Mansfield Park, but it’s become an object of great admiration for me if not outright pleasure. The scene there that continues to be marvelous to me is the drawing-room tableau she describes as Sir Thomas arrives home to break up the play, Chapter 19, and the ensemble sweats out the family reunion scene he wants to play before he discovers their theatrical production. “How is the consternation of the party to be described?” It’s perfect—Fanny watching everything, comprehending the room in complete displacement from herself. (Cf. this Daniel Lavery tweet). Sense and Sensibility so far? I’m missing some of the polish, to be honest. Not as rough-done as Northanger Abbey, but it’s no Persuasion, certainly. —Chris] [I’m just happy you’re coming around on Mansfield Park. —Steve]

Chris has been reading the book of Exodus as well [In the Robert Alter volume (The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, 2004), as usual. —Chris] and is finishing up Giorgio Agamben’s commentary on the epistle to the Romans (The Time That Remains, 2005), about which, more below. See also below, that he finished reading a short book of Reinhold Niebuhr’s (Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic, 1929).

Critical notes:

Agamben on the fate of western poetry:

I would like to end our exegesis of messianic time with the following hypothesis: rhyme, understood in the broad sense of the term as the articulation of a difference between semiotic series and semantic series, is the messianic heritage Paul leaves to modern poetry, and the history and fate of rhyme coincide in poetry with the history and fate of the messianic announcement. One example is enough to prove beyond a doubt that this is to be taken quite literally and show that this is not a question of secularization, but of a true theological heritage unconditionally assumed by poetry. When Holderlin, on the threshold of a new century, elaborates on his doctrine of the leave-taking of the gods—specifically of the last god, the Christ—at the very moment in which he announces this new atheology, the metrical form of his lyric shatters to the point of losing any recognizable identity in his last hymns. The absence of the gods is one with the disappearance of dosed metrical form; atheology immediately becomes a-prosody.

[There are a lot of delights to reading Agamben, but one I really savor is when he takes a few pages to, say, establish a thesis like “unrhymed poetry is godless.” On the very next page after this passage quoted he says something like, the hyphen is the only truly dialectical punctuation mark—go for it buddy, shoot for the moon. —Chris]

Niebuhr, in 1927:

Talked today at the open forum which meets every Sunday afternoon in the high school. The “lunatic fringe” of the city congregates there, in addition to many sensible people. The question period in such meetings is unfortunately monopolized to a great extent by the foolish ones, though not always. Today one old gentleman wanted to know when I thought the Lord would come again, while a young fellow spoke volubly on communism and ended by challenging me to admit that all religion is fantasy. Between those two you have the story of the tragic state of religion in modern life. One half of the world seems to believe that every poetic symbol with which religion must deal is an exact definition of a concrete or an historical fact; the other half, having learned that this is not the case, can come to no other conclusion but that all religion is based upon fantasy.

Fundamentalists have at least one characteristic in common with most scientists. Neither can understand that poetic and religious imagination has a way of arriving at truth by giving a clue to the total meaning of things without being in any sense an analytic description of detailed facts.

The fundamentalists insist that religion is science, and thus they prompt those who know that this is not true to declare that all religious truth is contrary to scientific fact.

How can an age which is so devoid of poetic imagination as ours be truly religious?

Autofiction’s allure for publishers is that it sells itself. Brouillette explains that “It is helpful to use authors’ biographies in marketing, attaching attractive and articulate real people to book titles; and authors are expected to work on this, to travel to promote their books on radio, TV, and the internet.” Similarly, Lee Konstantinou contends that autofiction’s distinctive “aesthetic gesture” is its “internalization of marketing into literary form, and the identification of self-promotion with the author function.” In both accounts, autofiction is not just a work of self-writing, but the work of self-promoting. What these accounts suggest is that contemporary autofiction can be understood not only as an aesthetic gesture, but a practical response to the economic pressures that authors face: the compulsion to sell the work as an extension of the self and the self as an extension of the work. Put differently, the novelist is no longer just a producer of fiction, but now also more directly responsible for the novel’s marketing and circulation, too.