WRB—May 25, 2024

The Reeses Witherspoon of Washington, D.C.

In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Washington, D.C., they had brotherly love, they had two hundred years of democracy and peace—and what did that produce? The Washington Review of Books.

N.B.:

The recording of last week’s WRB x Liberties salon, “Should you like your friends?” is now available wherever fine podcasts are distributed.

The next salon will take place on the evening of June 15th. If you would like to come discuss the topic “Propaganda: do you know it when you see it?” please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

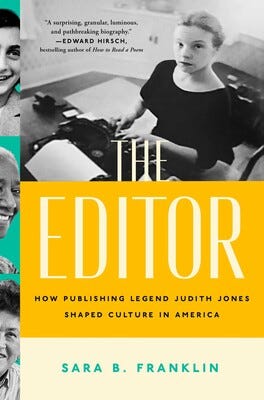

In Bon Appetit, an excerpt from Sara B. Franklin’s upcoming biography of Judith Jones (The Editor: How Publishing Legend Judith Jones Shaped Culture in America, May 28):

French Recipes for American Cooks was different from all the other French cookbooks. Judith saw that right away. “I knew from the tone, from the writing,” Judith told me, “that I was going to learn things.” Judith took the book home in pieces to cook from it with Dick; cooking together was the anchor of their domestic life. They started with the boeuf bourguignon. “First [Julia Child] told what kind of meat to use, which is so important,” Judith recalled. “And what kind of fat to use—if you brown the meat just in the butter, the butter burns. She told you not to crowd the pan, because you steam rather than brown the meat, and doing the mushrooms and the little onions separately. It just went on and on, these suggestions. I couldn’t believe it! Well, it was the best boeuf bourguignon we’d ever had!” Judith said. French Recipes actually taught readers how to cook. Judith thought it was revolutionary. The very book she’d been looking for had fallen right into her lap. But Knopf’s editorial board, Judith knew, was unlikely to be as enthused as she about such a project. Judith would have to channel her excitement into a convincing argument and a workable strategy if she wanted a chance at the book.

[An Upcoming book today; we linked to earlier reviews in WRB—Apr. 27, 2024 and WRB—May 22, 2024.]

In Slate, Alexander Sammon goes surfing at America’s second-largest mall:

All of that was changed in the pool. We all paid the same $250—plus tax, plus 6 percent service fee—to be here. Still, there were locals. “We’ve got a good group of regulars,” Lucas, who had been working at the pool nine months, told me, standing waist-deep in the shallow end with some of the beginners. “There’s a group of intermediate guys, and there’s a group of advanced guys who rip. A lot of dentists, actually.” I asked him how this current crew stacked up. Very solid, he assured me.

Most people I surfed with that night had been there only once, though one guy told me he’d surfed the morning session that day, at 8, and returned for the late sesh. Denis, a 31-year-old Frenchman, told me he’d been there 10 times at least. He wasn’t a dentist; he worked in finance.

In The Point, Jordan Castro on his influences:

My and Baker’s single interaction was meager, and, in my view, didn’t constitute a proper “conversation”: I had messaged him to ask if I could send him a copy of The Novelist (2022), after a review of another novel in the New Yorker opened with a sentence about The Novelist and mentioned The Mezzanine (1988) shortly thereafter. Baker replied with a message that began, “jeepers -,” which made my heart flutter; I was delighted by the “jeepers”—my first interaction with Nicholson Baker had included the word “jeepers”! What was the rest of the message going to say? I couldn’t think of any more appropriate word to pop up in my inbox beneath his name that could so thoroughly confirm my distant impression of him as “jolly”: jeepers! Before opening the message, I screenshotted it (while it was still unread, showing only his name, Twitter avatar and the first line of his message, “jeepers – let me try…”), and posted it on my Instagram story. But as I relished in the “jeepers” and responded to the Instagram story replies (“So cool!”; “No waaaay”; [heart emoji]), I neglected the central thing: I failed to actually respond to Nicholson Baker.

[I don’t think most of my influences would be on Instagram, were they alive now. —Steve]

In Engelsberg Ideas, Alexander Lee on the life of Machiavelli:

A few weeks later, Machiavelli was released in an amnesty granted to mark Giovanni de’ Medici’s election as Pope Leo X. After a brief period spent moping in Florence, he retreated, a broken man, to his farmhouse in Sant’ Andrea in Percussina, a few kilometers to the south. There, he became a gaglioffo—a good-for-nothing. As he told his friend Francesco Vettori, he spent most mornings in the woods, chatting with neighbors, or reading a book of poems by the stream. At lunchtime, he returned home to eat with his family, before heading to the tavern. The rest of his day was spent “slumming around” with the locals, drinking and playing cards or backgammon. When in their cups, they’d often argue—generally over nothing more than a penny—and every so often, a fight would break out. It suited Machiavelli, though. It helped him to “get the mold out of [his] brain and let out the malice of [his] fate.”

[The Prince is a guidebook for managing editors. —Steve]

In UnHerd, Jonathan Glancey on John Betjeman:

His relationship with women—he had a wife, a long-term mistress and a secret lover on the go late in life—produced poems that can seem absurd even to loyal fans. Those big, domineering and sometimes quite grotesque Amazonian “gels”. Those jolly hockey-stick types on bicycles and in Sussex tea rooms. The svelte “mistress” with “more than a cared-for air / Than many a legal wife” he lusts after in church. Sometimes, though, he is more lyrical. In “A Russell Flint” he writes, “I could not speak for amazement at your beauty / As you came down the Garrick stair”, and in “Youth and Age on Beaulieu River”, of Clemency the General’s daughter, sailing on the Hampshire water, “Soft and sun-warm, see her glide / Slacks the slim young limbs revealing, / Sun-brown arm the tiller feeling / With the wind and with the tide”.

[The first Betjeman I encountered, and the only work of his I knew for a while, is the one on Slough, which looking back is both representative and not. —Steve]

In The New Yorker, Hanif Abdurraqib interviews Diane Seuss about her most recent collection (Modern Poetry, March):

And so in the book, to be honest, it’s mysterious to me the connection between the modern and romantic poetry-wise, and then my exploration of romance as a trope or the romantic in myself. I really let myself go in that poem, where I am young and I go to Italy and make out with Keats’ death mask and leave my lipstick marks on it, and then I’m holding him and listening to the fountain. Part of me thinks, God, Diane. But that’s where I’m beginning to remember what poems can be and do for me. In that poem, I’m in New York in the beginning, and I go to Italy, and there’s something that is capable of transporting me back in time but also into a different kind of present tense, a romantic intensity, a holding that I haven’t allowed myself in a long time. And I think poetry can uncover the layers of cement that build up around us and transport us there for a moment. I had somebody in my arms. Isn’t that a trip?

In Wayfare, A.M. Juster interviews John Talbot:

Juster: Did you come away with any anecdotes about [your colleagues at Boston University]?

Talbot: I went to Geoffrey Hill to see if he would serve on a thesis committee for one of my students. He agreed, but surprised me by adding: “On this condition: that you not reveal to him my Sunday afternoon hobby of turning verses.” That’s very nearly verbatim. Here was the greatest poet of the last half of the twentieth century, trying to conceal the fact he was a poet. He said this with a straight face. I wanted to say, “If you don’t want people to know that you write poetry, perhaps you ought to stop writing all those books of poetry.”

In the Journal, Daniel Handler (better known as Lemony Snicket) on living with “haunting visions”:

Occasionally we took supervised walks, blinking in the sunshine within a two-block radius. On one of these walks, I heard someone call my name. It was my Nabokov professor, a middle-aged woman in a beat-up car, who seemed both surprised and not surprised to see me there. We had only a brief conversation, but it jogged something in my troubled mind.

In one of my favorite Nabokov novels, the relatively obscure Invitation to a Beheading, the hero experiences something akin to what I was feeling there with my professor. Condemned to death, the hero is hit with a clarity, “at first almost painful, so suddenly did it come . . . why am I here? Why am I lying like this? And, having asked himself these simple questions, he answered them by getting up and looking around.”

Reviews:

In The New Criterion, Patrick Kurp reviews a collection of William Maxwell’s writing (The Writer as Illusionist: Uncollected & Unpublished Work, edited by Alec Wilkinson, January) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Nov. 22, 2023; we linked to an excerpt there as well.]:

Maxwell was a domestic realist who shunned postmodern games, yet his narrators are sometimes self-reflexive, and they often comment broadly or obliquely on the story at hand. They are cousins to George Eliot’s narrator in Middlemarch, but quieter, less discursive. The effect is not dictatorial but amiable, in the manner of a friend who wishes to encourage and console without appearing pushy. Wilkinson describes Maxwell’s fiction as a “collage-like interplay among observation of the present, the imaginative life, and the pull of memory.”

N.B. (cont.):

Robert Christgau on Ezra Koenig: “It’s the rare artist who has any feel for criticism as a craft or calling and I’m even better at mine than he is at his.”

On the subject of artists who may or may not have any feel for criticism as a craft or calling: Bob Dylan’s 83rd birthday was yesterday.

Department of Managerial-Editorial Mispractice: We neglected to highlight for you, our loyal readers with whom we hold so much trust, this line from the Times review [Linked in WRB—May 1, 2024] of Honor Levy’s recent collection (My First Book, May 14), luckily noticed by Helen Lewis: “‘Muriel Spark lived long enough to write a series of online diaries for Slate.’ What.”

The New Atlantis is looking for contract editors.

New issues:

The New Criterion June 2024 | Volume 42, Number 10 [As linked to above.]

The Point Issue 32 | Spring 2024 [As linked to above; there’s a series of essays on masculinity in this one, which is one of the most miserable essay topics out there. (Up there with “AI.”) I’m always baffled that anyone has managed to think about it for long enough to write an essay. Speaking as a man, in my own life I have other things to do—go to work, have beautiful female friends, wish I were living the plot of Sentimental Education, work on this newsletter, and so on. “Gender? I hardly know ’er!” and all that. —Steve]

Local:

A reader told Chris with great emphasis this week that the Matchbox Magic Flute now playing at the Klein Theater is, quote, ridiculous, silly, and completely delightful, end quote, so consider yourselves, fellow readers, duly informed.

The WMATA is seeking feedback about a bus route redesign.

The local Post is “in a hole,” says its CEO.

The Capital Jewish Museum has an exhibit about Jewish delis on display through August. [This newsletter supports drinking Cel-Ray. —Steve]

Poem:

“Another Room” by Phillis Levin

There is another room

You could spend time in.

What a shame not to enter

More often: walls a colorHard to imagine, windows

Overlooking a shy garden.

From there it is easy to see

A neighbor pinning laundry,Composing a line of forlorn

Collars and sleeves

Punctuated by buttons

Catching the afternoon sun,Whose face was a stranger

Until their mother-of-pearl

Was torn from a bed in a reef.

Whenever a chance to returnReturns, you wonder why

You didn’t sit in that sofa,

Alone or near someone

In a chair, watchingA robin abandon

The swaying branches,

Listening to rain on the roof,

Undersong of comfort,Undersong of grief.

A lifetime could be wasted

Dreaming there, a lifetime

Wasted not dreaming there.

[This is from Levin’s 2016 Mr. Memory & Other Poems, her fifth collection.

This poem has such a lovely, gentle voice, and I love this room that Levin brings into soft focus. It’s elusive and muted, with the hard to imagine color of its walls, its shy garden, and the forlorn laundry next door. And yet at the same time it’s welcoming and in some way essential: there, it’s easy to see. What a shame to not enter / More often, we’re told. But the poem doesn’t view muted and welcoming, or elusive and essential, as opposites; look at the way the sound of rain hitting the roof is described: it’s both the Undersong of comfort and the Undersong of grief at once. The poem’s comfort with its own contradiction continues right through the last sentence: A lifetime could be wasted / Dreaming there, a lifetime wasted not dreaming there. That sentence could be read as a bleak, no-win situation, but that’s not how it feels to me. What I hear in that line, instead, is the speaker acknowledging in the first clause that many people view dreaming as a waste of a life, but then—in the latter half of the sentence—she’s insisting that dreaming is itself essential. It’s a waste of a life to never do it. Which reminds me a bit of Wednesday’s Poem from Ilya Kaminskey: the heart needs a little foolishness!

I also love this striking visual we get of the sun caught by the mother-of-pearl buttons, the sun that was a stranger // Until their mother-of-pearl / Was torn from a bed in the reef. That sentence contains such a wide physical distance, all the way from the seafloor to the sun. Yet it’s a image marked more by immediacy and closeness: the once-stranger now reconciled, and reconciled by a harvesting that, at least on the level of word choice, borders on violence (torn from a bed, which, in its physicality, is another image of closeness).

The point of all of this analysis, I think, is that to me this is a poem for wandering through more than it is for deciphering. Honestly, I couldn’t tell you what this “other room” is, or how to get there. But this poem, with its lines that are short without being cramped, its enjambments that are largely syntactic without being overly-predictable, and all of its wonderful complexity, is a comforting place to dwell in, despite its elusive nature. In that way, it’s much like the described room itself. —Julia]

Upcoming books:

May 28 | Atria Books

The Editor: How Publishing Legend Judith Jones Shaped Culture in America

by Sara B. Franklin

From the publisher: Judith’s work spanned decades of America’s most dramatic cultural change—from the end of World War II through the Cold War, from the civil rights movement to the fight for women’s equality—and the books she published acted as tools of quiet resistance. Now, her astonishing career is explored for the first time. Based on exclusive interviews, never-before-seen personal papers, and years of research, The Editor tells the riveting behind-the-scenes narrative of how stories are made, finally bringing to light the audacious life of one of our most influential tastemakers.

Also out Tuesday:

Catapult: Accordion Eulogies: A Memoir of Music, Migration, and Mexico by Noé Álvarez

What we’re reading:

Steve did what he mentioned on Wednesday and read the intro and the first essay in the NYRB Max Beerbohm collection. [I laughed out loud multiple times, which I rarely do when reading, especially not in the span of seven pages; more about the intro below. —Steve]

Julia read more of Joanna Biggs’ A Life of One’s Own: Nine Women Writers Begin Again (2023).

Critical notes:

Woolf on Beerbohm (quoted in the above-mentioned intro):

Once again, we have an essayist capable of using the essayist’s most proper but dangerous and delicate tool. He has brought personality into literature, not unconsciously and impurely, but so consciously and purely that we do not know whether there is any relation between Max the essayist and Mr. Beerbohm the man. We only know that the spirit of personality permeates every word he writes. The triumph is the triumph of style. For it is only by knowing how to write that you can make use in literature of your self; that self which, while it is essential to literature, is also its most dangerous antagonist. Never to be yourself and yet always—that is the problem.

[In other words, the advantages, and problems, of editors’ notes in the WRB. —Steve]

Writers, who must be read in order to survive, have generally responded to this cultural schism—recently schematized by Anna Kornbluh as the rift between form and immediacy—by either embracing a first-person approach, which values authenticity, reliability, and mundanity (you can’t read, but neither can I), or by embracing craft (I can read better than you).

[Speaking of approaching this work; I assume I can read better than some of our readers, and I also assume that some of our readers can read better than me. I have a high enough opinion of my writing to think that, between the content and the style, there’s something for everyone. —Steve]

Adam Roberts on Coleridge’s thoughts on life after death, the longaevi, and the Rime:

What is water, in Coleridge’s poem? The desert ocean, vast and hostile to life, salt and drear, death in endless motion? Or perhaps: the ocean, teeming with life (like the water-snakes that moved in tracks of shining white, the blessing of whom frees the Mariner), the pathway to adventure, empire and freedom, the sublime and beautiful waters? In Genesis the deep predates the cosmos, and Coleridge’s own God broods over it before speaking the universe into being.