WRB—May 4, 2024

“the evangelical peacock”

To the gross world of Washington, enslaved by commerce, respectability, and middle-age, it might have been anything; but the sons of fire who had similar oblongs protruding from their own breast-pockets knew what it was: it was a Print Edition of the Washington Review of Books, worn where it should be worn, just over the heart.

N.B.:

This month’s WRB Presents event will take place on May 14, organized with our friends at the Cleveland Review of Books, and will feature readings from Malcolm Harris, Joseph Grantham, and Margarita Diaz. As last time, doors are at 6, and the readings begin at 7.

The next WRB x Liberties salon will take place on May 18. If you would like to come discuss the topic “Should you like your friends?” please contact Chris or Celeste Marcus.

Links:

In the Journal, James Marcus on Emerson’s finances:

Sometimes Emerson could get tangled up in his own conflicting impulses about money. In the early 1860s, for example, his Boston publisher contacted Emerson about one of his articles that had previously appeared in The Atlantic magazine. There was now a plan to publish the same piece in a book, and so a check had been cut for the Sage of Concord—which he refused. “I don’t believe it honest for me,” he insisted, “to take money twice for the same piece of work.” He had an old-fashioned work ethic, believing that he had been paid for an honest day’s labor and the accounts were thereby balanced.

The publisher pleaded with him to accept the payment. Emerson, softening, wondered whether he should stick to the high road after all. Weren’t his principles simply gumming up the sacred machinery of supply and demand? “We cannot live in obedience to the true poles of our being,” he allowed. “I vary from my highest self, and I have no disposition to play the evangelical peacock here.” To put it another way: he took the check.

[Who among us? —Steve]

Alan Jacobs on Dorothy Sayers and the middlebrow:

Not well educated, not generously gifted, instinctively (not consciously) moved to create a whole but capable of constructing only the “rickety and ramshackle,” the common reader can only form “insignificant” ideas and opinions. Lovely.

Sayers would agree with some of this. But she did not think the ideas and opinions of the common reader insignificant; indeed, she thought them typically superior to the opinions of highbrows. More important: while Woolf takes the shortcomings of “the common reader” as givens, almost as natural phenomena like mushrooms or cloudy days, Sayers, by contrast, sees any such deficiencies as remediable—and sees such remediation as part of her responsibility as an intellectual.

In The Nation, Devin Thomas O’Shea on Jack Conroy and the left-wing literary movement he tried to support and inspire:

Conroy was a pragmatist: His focus was on regular people. He claimed the sight of Das Kapital on a shelf was enough to give him a headache, and he warned of the alienating danger of the “lower case” and “expatriate” journals publishing writers who had left America for Paris. The high modernists produced complicated experimental work, developing a form that only the intellectual connoisseur could keep up with. “Eccentricity is not an inevitable corollary of merit,” Conroy wrote. “Fidelity to life is always the final and only trustworthy touchstone.” Balzac, Swinburne, and Shelley developed the poetics that Conroy embraced, and his stories concerned such things as the burden of pregnancy for the poor, the starving conditions of wage labor, and the itinerant global working class rapidly developing in the Great Depression.

[I got whiplash upon reading that a man who claimed that “Eccentricity is not an inevitable corollary of merit” and that “Fidelity to life is always the final and only trustworthy touchstone” was indebted to Swinburne. (Having given this more thought than it probably deserved, I can only conclude that his focus on “regular people” led Conroy to—I understand that this is what he is complaining about but there are no other words—an incredibly vulgar understanding of poetry as the art of skillful rhyming and stringing together word after word, phrase after phrase, image after image, all possessed of a poetical quality. By these standards, Swinburne may be the best to ever do it.) There’s a reason that what may be the greatest sentences in the greatest piece of negative criticism state of Swinburne: “It is historically certain that he had seen the sea, but if it were not, it could not with certainty have been inferred from his descriptions: they might have been written by a man who had never been outside Warwickshire. Descriptions of nature equally accurate, though not equally eloquent, have actually been composed by persons blind from their birth, merely by combining anew the words and phrases which they have had read to them from books.” —Steve]

In our sister publication Down Under, Anwen Crawford on cricket, writing, and writing about cricket:

School matches, county matches, Test matches: Hughes was at them all. It’s clear from her accounts that she loved to be part of an audience—a recommendation in any critic. She delighted, for instance, in the wit and expertise of followers of the victorious West Indies team that toured England in 1950; these Londoners, the first of the Windrush Generation, “knew every cricketer, every score and every record.” Hughes insisted that Test cricket should have entertainment value, a principle she shares with many contemporary observers of a sport notorious, not least among its fans, for lapsing into stagnancy. (I wonder what she would have made of Bazball?) By her measure, great players are the ones who bring “the qualities of life”—humor, artistry and excitement—to the field. “A batsman who is dull and stolid, dour and ungainly, gives little to the game,” she pronounces. Lord’s deliver us a stylist, in cricket as in literature.

Two in our sister publication on the Thames: first, Julian Barnes on the funny process of trying to remember art:

But memory is such a shifty and shifting process, constantly duping us. As far as it is possible to generalize, I think we misremember small pictures as being larger than they are, and large pictures as smaller. Also, what we are remembering is not just the painting itself but its effect on us; and some parts of it will inevitably remain fresher than others. At least, in this age of mass color reproduction, we can always check our memories—or so we believe. In my early decades, going to an art gallery abroad always culminated in a good deal of time spent at the postcard carousels; and over the years I have accumulated a vast collection of cards which I can use to check my memory. This “check” can only be partial, however: there is the question of size (how accurately can and do we scale the image up?) and also of color fidelity. I have a friend who, when she first started looking at art, would never buy a postcard of a painting she admired, for fear that the original would be supplanted in her memory. This was properly high-minded, but in practice, she reported, her remembered images were still subject to normal deterioration.

[Near the end Barnes writes “For instance, memory rarely lets you down with Hockney’s work, clean and clear, memorable in the best way, and normally just the same when revisited, whereas you might be hard put to describe from memory a Rothko—though you might better recall its overall effect on you.” I suspect that there’s a similar phenomenon with novels, determined by the prominence of specific plot details in the memory. —Steve]

Reviews:

Second, David Trotter reviews a new collection of Emily Brontë’s work (Emily Brontë: Selected Writings, edited by Frances O’Gorman, March):

Heathcliff’s redounding occupies the greater part of Volume Two. Few fictional protagonists can have left a firmer or more calculated footprint on a milieu or environment than he does. It’s his redounding that generates the brutality that shocked Charlotte and Anne when Emily first read them Wuthering Heights. Discussing the strong element of Gondolian fantasy in the novel, O’Gorman remarks that the “distance” it maintains from the “fabric of lived experience” is most evident in its “figuring of violence.” But Brontë’s primary concern was always with repercussion rather than with motive. She meant her figuring of the ways people deal with violence to hew as closely as possible to the fabric of lived experience. Take Isabella Linton, Edgar’s sister, for example. We’re sometimes told that Brontë took little interest in Isabella except as a delivery system for the child Heathcliff requires if he is to gain legal ownership of the Grange after Edgar’s death. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Isabella suffers relentless physical and emotional violence from Heathcliff. Brontë went out of her way to ensure that she told this tale of domestic abuse—no further from lived experience today than it must have been then—in her own words.

[Worth noting that no adaptation of Wuthering Heights for film, a medium that loves fantastic violence, that I’ve seen is nearly as violent as the book. —Steve]

In the TLS, A. E. Stallings reviews a book about Anne Carson (Anne Carson: The Glass Essayist, by Elizabeth Sarah Coles, 2023) as well as her latest collection (Wrong Norma, February) [We linked to two previous reviews in WRB—Feb. 7, 2024 and one in WRB—Apr. 24, 2024.]:

Coles ends her book with a chapter on If Not, Winter (2002). This is an illuminating choice, being among the most straightforward (or, if you like, least gimmicky) of Carson’s works. We have tantalizingly few nearly complete poems of Sappho, and many of the fragments we have retained are ambered in quotations from other contexts. Here is Carson at her most glassily transparent: the facing Greek announces that in crossing the border into English, the English has “nothing to declare.” The right-hand brackets indicate lines or parts of lines we know to be missing, and hold open windows of silence. Yet despite minimal Carson interference, the result is somehow even more a blend of the two authors. Coles points out that Sappho “quotes” Carson verbatim: fragment twenty-two’s “you beauty” has been “previously” spoken in “The Glass Essay.”

[The second excellent piece I’ve read recently inexplicably marred by the cliche about the meaning of the word “essay.” (Ann Manov’s Bookforum review was the other.) Maybe we should give essays a new name to avoid this. —Steve]

In Literary Review, Morten Høi Jensen reviews a new edition of Kafka’s diaries (The Diaries of Franz Kafka, translated by Ross Benjamin, 2023) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Jan. 7, 2023; we linked to excerpts and an earlier review in WRB—Jan. 11, 2023.] and two books about him (Metamorphoses: In Search of Franz Kafka, by Karolina Watroba, June 4; Kafka: Making of an Icon, edited by Ritchie Roberston, August 30):

Benjamin’s most crucial departure from Brod is his restoration of the diaries’ open-endedness. His edition reveals how the preoccupations of Kafka’s fiction—alienation and loss, shame and guilt, futility and repetition—grew out of his circumscribed life, so much of which was spent negotiating the demands of the everyday: noise from a nextdoor apartment, the petty encumbrances of office culture, spending an evening in the company of a friend’s unbearable spouse. It is not even always clear whether a given entry is fictional or not. As Benjamin explains, by restoring Kafka’s many drafts, dream notes, false starts, cryptic fragments, letters and stories, he has attempted to preserve the original manuscripts’ “rough edges,” allowing us to peer into the “laboratory for Kafka’s literary production” for the first time.

Lydia Davis on her short story “Kafka Cooks Dinner”:

I used to read his diaries very closely and very often when I was younger. I think I felt very close to him. He was never proud or arrogant. I’m sure he had many facets to him, but I found him a very sympathetic, lovable person. I felt very comfortable appropriating him for this dinner situation.

The story started as just a neat idea, because I was having trouble thinking what to make for dinner. And I thought how much more trouble he would have had because he was such a hesitater. It was going to be just a page or so, but then I decided to incorporate his language into it. It grew and grew because I went to his letters, too. And I wanted to incorporate all the wonderful things he says in them, like “Someone once said I swim like a swan, but it was not a compliment.”

[It’s a great story. The appearance of the phrase “Kartoffel Surprise” three times in the opening paragraphs makes me laugh, which somehow feels like the appropriate mood to be in for it. —Steve]

Two in our sister publication on the Hudson:

Ange Mlinko reviews collections of the poetry of Denise Levertov (The Collected Poems of Denise Levertov, edited by Paul A. Lacey, January) and Anne Stevenson (Collected Poems, 2023), who emigrated across the pond in opposite directions:

No wonder Andrew Motion called her “a puritan writer who at once honors and contests her inheritance.” There’s also more to the story than what appears in the poem: when Stevenson returned to England after her fellowship, she left her husband and young children for her lover, the poet Philip Hobsbaum. It was while she was suffering from bereavement and a bad conscience that she finished Correspondences (1974), where at the end of the New England family line stands a woman who acts defiantly, if selfishly, no matter the personal cost. “I learned how to put experience into poetry without ‘confessing’ it,” she wrote in her 1979 essay “Writing as a Woman.” Her protest took a different form from those of Levertov and other American peers; despite drawing inspiration from Williams for the free verse of Correspondences, it was this book that signaled her permanent leave-taking, her “good-bye to all that.”

Catherine Lacey reviews a new translation of a novel by Alba de Céspedes (Forbidden Notebook, 1952, translated by Ann Goldstein, 2023):

Riccardo, without directly saying it, is telling his mother that Clara’s relationship with Michele should be a humiliation—women cannot be friends with men because of their innate inferiority, and thus their sexual relationship is blatantly obvious. Though Valeria believes this to be true, she doesn’t want it to be true, and there is the crux of her obsession with Mirella: her daughter represents a different possible future for women, one that Valeria both craves and distrusts. Even if Mirella’s hopes to reach this “new position in society” are met, Valeria will always be imprisoned in her generation.

When Valeria finally does meet Cantoni, she realizes that her daughter’s choices are a refutation of her own disempowered life. Cantoni is quite a bit older than Mirella and is still in the process of divorcing his first wife. When Valeria asks how long it will take him to marry Mirella, Cantoni explains, “Marriage isn’t our goal, we don’t want to be obligated to love each other; every day we choose freely to love each other. You understand, right?” Of course Valeria does not understand, but she tries to look at him “with Mirella’s eyes.” The scene has a confused, painful romance to it; it’s unclear whether she’s jealous of their relationship or simply finds such seemingly equal love impossible to comprehend.

N.B. (cont.):

“The Diminishing Returns of Having Good Taste” [There’s a conflation of “knowing what the cool thing is” and “being able to say interesting things about it” here, and the internet can much more effectively kill the first. —Steve]

Someone is stealing rare editions of Pushkin from European libraries.

The Possessed:

It was impossible, of course, to remain any longer in Petersburg, all the more so as Stepan Trofimovitch was overtaken by a complete fiasco. He could not resist talking of the claims of art, and they laughed at him more loudly as time went on. At his last lecture he thought to impress them with patriotic eloquence, hoping to touch their hearts, and reckoning on the respect inspired by his “persecution.” He did not attempt to dispute the uselessness and absurdity of the word “fatherland,” acknowledged the pernicious influence of religion, but firmly and loudly declared that boots were of less consequence than Pushkin; of much less, indeed. He was hissed so mercilessly that he burst into tears, there and then, on the platform. Varvara Petrovna took him home more dead than alive.

The New Atlantis is soliciting submissions about “what, exactly, we should be building.”

New issues:

The Brooklyn Rail May 2024

The Jewish Quarterly 256 - May 2024

Literary Review May 2024 [As linked to above.]

Spike Issue 79 (Spring 2024)

An Extra Edition of the European Review of Books

Local:

RFK Stadium has been cleared for demolition.

The Reston Regional Library is hosting a book sale with a “record-setting number of books” today from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and tomorrow, May 5, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Poem:

“Genesis III” by Nicole Robinson

The jellyfish, clear but filmed in its slime,

is dead on the shore, wordless as always.

I’m stupidly in love with the story

I’ll never know of its life. I turn it over

with a stick, careful not to deflate it.

[This is from Robinson’s 2023 Without A Field Guide, her first collection.

This is the shortest poem in the collection, but its clarity and concision is a constant throughout the book, even in Robinson’s longer poems. The other notable constant throughout the book, to me, is the subtle but sharp tension that we see in this poem. Wordless as always connotes a mixture of disappointment and resignation, but there’s also a sense in this poem that the speaker somehow wants that wordlessness, even as she’s conflicted about her own desire for it: I’m stupidly in love with the story / I’ll never know of its life. I love that moment of the speaker’s admission of fondness for her own ignorance. What I think is so interesting in that sentence is that it’s not that the speaker loves her ignorance because it allows her to imagine whatever she wants about the jellyfish’s life; the love is directed toward the reality of the thing, even though it’s an unknown reality: the story / I’ll never know.

The thing about this collection that got me most, honestly, is the fact that two of its poems make use of an eastern Ohio infinitive copula deletion (the uses in question being say what needs said and What we find needs found), which is a construction that I love. I don’t think I’ve ever seen it in a published collection before. —Julia]

Upcoming books:

May 7 | W. W. Norton & Company

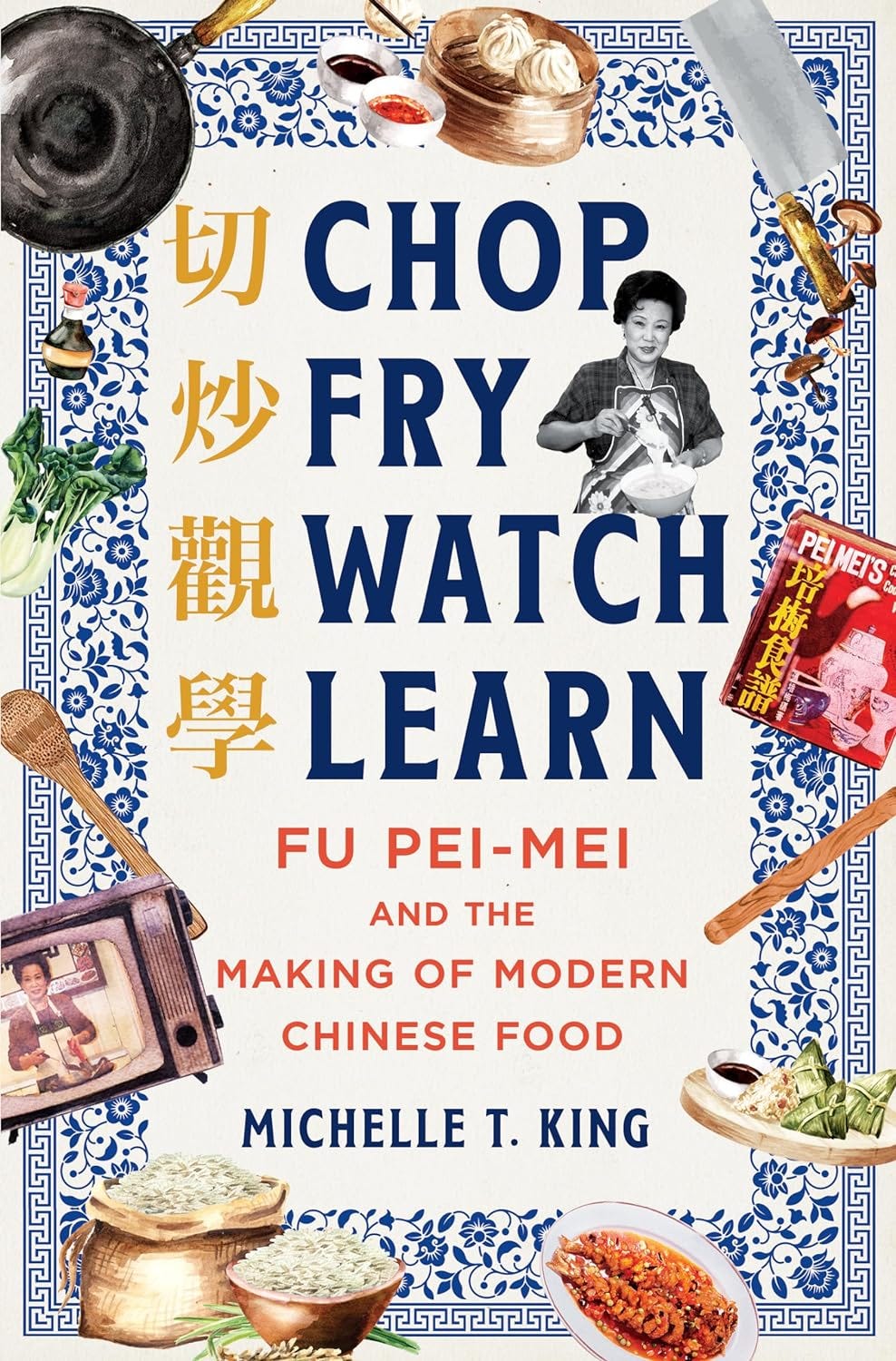

Chop Fry Watch Learn: Fu Pei-mei and the Making of Modern Chinese Food

by Michelle T. King

From the publisher: In 1949, a young Chinese housewife arrived in Taiwan and transformed herself from a novice to a natural in the kitchen. She launched a career as a cookbook author and television cooking instructor that would last four decades. Years later, in America, flipping through her mother’s copies of Fu Pei-mei’s Chinese cookbooks, historian Michelle T. King discovered more than the recipes to meals of her childhood. She found, in Fu’s story and in her food, a vivid portal to another time, when a generation of middle-class, female home cooks navigated the tremendous postwar transformations taking place across the world.

In Chop Fry Watch Learn, King weaves together stories from her own family and contemporary oral history to present a remarkable argument for how understanding the story of Fu’s life enables us to see Chinese food as both an inheritance of tradition and a truly modern creation, influenced by the historical phenomena of the postwar era. These include a dramatic increase in the number of women working outside the home, a new proliferation of mass media, the arrival of innovative kitchen tools, and the shifting diplomatic fortunes of China and Taiwan. King reveals how and why, for audiences in Taiwan and around the world, Fu became the ultimate culinary touchstone: the figure against whom all other cooking authorities were measured.

Also out Tuesday:

Hanover Square Press: The World Is Yours: The Story of Scarface by Glenn Kenny

Spiegel & Grau: Shanghailanders by Juli Min

What we’re reading:

Steve read more of Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton (2023). He also read What If?: A Closer Look at College Football’s Great Questions by Matt Brown (2017).

Julia finished Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me and started Eileen Simpson’s memoir of her marriage to John Berryman, Poets in Their Youth (1982).

Critical notes:

Helena Aeberli on the problem of the “literary it-girl”:

None of this is strictly a bad thing—if anything, it’s refreshing to see women moving away from the self-infantilizing girlhood culture of the past couple of years and embracing markers of intelligence and artistry. Yet at the same time it speaks to our desire to consume surface level content rather than engage meaningfully with art, and to the image-obsessed online world which sees the book as a commodified marker of status increasingly adopted into the “hot girl” arsenal. . . . As A. V. Marraccini writes in her electric manifesto “Hephaestus Contra The It Girl”: “The It Girl is them selling you the idea of the thing you are supposed to want to be.”

So whilst this new turn towards intellectual aesthetics might be an attempt to give girl discourse a more substantive base, it feels equally as reductive. We can’t just be writers; we have to be girl writers, in which girl is conjoined to an invisible adjective: hot.

[I love Aeberli’s analysis here. I agree with her that the “literary it-girl,” as an ideal, has more good in it than some other constructions of female desirability, and she’s also right to point out that it is, ultimately, still just another way of selling female desirability. Which is to say the obvious: it can easily become about hotness at the expense of substance.

Little of what Aeberli points out is entirely new, either. Like she notes, singling out writers who are women as women writers isn’t always constructive. It has important reasons, of course: to counteract to the ways women have been marginalized, or to celebrate their distinctive lens as women, but it also can turn women’s writing into a kind of separate “league,” as though it’s a sport where women only compete against other women and not with men—or, worse, makes women writers into something like women’s razors: their “packaging” becomes focused on their femininity over other qualities. (Bishop, for one, repeatedly turned down requests to be included in anthologies of women poets because she didn’t want to be viewed as only a woman poet.) —Julia]

Justin Smith-Ruiu on internet humor:

I hate, but really hate, McSweeney’s. Every time I start reading it I think: Am I reading “Reader’s Digest Presents: The ‘Lighter Side’ . . . Of Graduate School!”?

Victoria Moul on the death of Antony:

Cavafy’s poem acknowledges the grandeur and reality of such turning-points and links this to personal courage in the face of disaster. His poem urges his addressee to an absolute dignity of which Antony in the end is deprived—in Plutarch (as in Shakespeare), after botching his suicide, he is hauled up by ropes to Cleopatra as he is bleeding to death. In Shakespeare, there’s a rough kind of comedy to the scene alongside its pathos: “Here’s sport indeed. How heavy weighs my lord!” says Cleopatra, as she strains on the ropes. Cavafy imagines, instead, someone who has “long prepared” for the moment of reckoning, an exhibition of stoic self-control more reminiscent of Horace’s Regulus (from Odes 3.5) than of Shakespeare’s Antony.

Nicholas Dames and John Plotz interview John Guillory about his latest book (Professing Criticism: Essays on the Organization of Literary Study, 2022):

What I wanted to show was that by the later 1960s, judgment was returning in the mode of, not the criticism of the literary work, but the criticism of society—interpreting literary works in order to arrive at a judgment of society.

What happened was what I call the “reassertion of criticism,” but the reassertion of criticism with this different end, with this different purpose. Some of that judgment redounded back on literary works, so that it was possible for a number of scholars to judge the literary works themselves as morally and politically objectionable. That’s presented us with this perennial problem of, when we do talk about literary works in the context of the criticism of society, what do we want to say about the value of literary works themselves in that context?

Is the value of the literary work its capacity to disclose aspects of society that need to be judged adversely? Or is the value of the literary work its transcendence of those conditions in society that need to be pointed out, condemned, and ultimately be averted?