WRB—Nov. 18, 2023

“the insides of a lobster”

We are desperate for information about how other people read because we want to know how to read ourselves.

Links:

In our previous issue we mentioned Little Women. We return to similar material in the Times with Elisabeth Egan on the 100th anniversary of Emily of New Moon (1923), another novel by L. M. Montgomery, author of Anne of Green Gables (1908):

Emily is a scrappier, more complex character than Anne, with a wicked temper and a refreshing candor. When classmates ridicule her apron, her bonnet, her ears and, finally, her uncle, she threatens them with the evil eye, then defuses the situation by asking, point blank, “Why don’t you like me?” She refuses to bend to her aunts’ rules even when it means burning her writing to avoid their scrutiny. When she experiences “the flash”—that rare, inspiring moment when she feels she can peer into another world—she pays attention.

“She could never recall it—never summon it—never pretend it,” Montgomery writes, “but the wonder of it stayed with her for days.”

The Managing Editors continue to be on their The Once And Future World (2013) beat about the decline of animal species once much more abundant and wide-ranging. In Grist, Max Graham details the effects of the declining salmon runs up the Yukon River on the Alaska Native population living on its banks:

The disappearance of so many chums and kings has been the subject of growing scientific inquiry. For years, the vanishing kings posed an ecological mystery because the Yukon flows mostly unimpeded — untouched by the sort of industrialization that has destroyed salmon habitat in California, Oregon, and Washington. The river’s salmon don’t have to contend with large-scale dams that block passage to spawning grounds, clear-cuts that destroy streams, or mega-farms that siphon off water.

But salmon are notoriously difficult to study. They spawn in fresh water, then spend most of their lives far out in the Pacific, an area dubbed the “black box” because it’s so vast and poorly understood. Most salmon research—in Alaska and along the entire Pacific Coast—is focused on streams and lakes, where it’s easier to study their habitat, sample the water, and count stocks.

On that same beat, a new study investigating how wolves change beaver activity:

As these toothy engineers pursue their projects, the wolves are “like permitters, in some sense,” said Thomas Gable, project lead for the Voyageurs Wolf Project, and an author of both papers. “They’re like, ‘Nope.’”

In Interview, Ryan Ruby interviews Bennett Sims about his new short story collection (Other Minds and Other Stories, November 14):

I was interested in thinking of technology as a new kind of space that might be haunted by the unconscious of the characters. In Unknown, which is a story about possessive jealousy and paranoia, the smartphone was this ready-to-hand prop for externalizing all of the jealous paranoia, because the smartphone is, first and foremost, a tool of surveillance. For something like The Postcard, which is a noir-ish detective story about someone both traveling to a strange place and also traveling into the past, the robotic voice commands of a GPS system became this increasingly uncanny third character guiding the protagonist. The GPS voice becomes a haunted extension of his own sense of displacement in this unfamiliar landscape. Portonaccio Sarcophagus, the street view story, was organized around effacement. The titular sarcophagus in question has these unfinished figures on it where their head should be and the narrator becomes really interested in those and starts connecting them with other images: from a family photograph that seems to feature this ghostly apparition without a face in the background, to the horror movie The Ring. I am not the first person to connect the facial distortions in The Ring to the facial recognition blurring in Google Maps.

Reviews:

In our sister publication in the Forest City, Nina Pasquini reviews Annie Ernaux’s latest (The Young Man, translated by Alison L. Strayer, September):

But Ernaux retains a level of self-awareness about her crafting of this story. The words she uses—“reenacting scenes…from the play of my youth”—indicate a recognition that these are scenarios that she’s set up, not some omnipotent interpretation of events. And while Ernaux is no longer the younger woman with no past or future, to whom things happen, she does not fall back on a traditional narrative structure of linear progress. Rather, she examines how A. shows her a new way of understanding life: as a “strange and never ending palimpsest.”

In The Point, Ross Benjamin reviews Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel of German reunification (Kairos, translated by Michael Hoffmann, June):

It is not the final disillusionment of the novel. In an epilogue that takes place after Hans’s death, Katharina discovers from his Stasi file that he had been treacherous not only in his marriage and personal life, but also in his professional sphere. He had collaborated with the secret police by spying on his colleagues in East Germany’s cultural arena. Together, the prologue and epilogue frame the novel as a multilayered inquiry into what it means to grieve something that is irretrievably gone but that you wouldn’t actually want back, to feel homesick for a place to which you wouldn’t want to return even if you could. Perhaps the real grief is for wishes and hopes that were erased together with the world that had failed to realize them.

In the local Post, Maureen Corrigan reviews Benjamin Taylor’s biography of Willa Cather (Chasing Bright Medusas: A Life of Willa Cather, November 14) [One of the Upcoming books in WRB—Nov. 11, 2023.]:

Two summers ago, during my brief pilgrimage to Red Cloud, I was fortunate to be shown the place where Cather’s transformations began: the “story-and-a-half frame house” that her parents bought in 1885 for their growing family. I climbed to the attic dormitory and peered into the shadowy little room, “a corner of the L-shaped attic” that had been partitioned off for Willa alone. Her girlish flowered wallpaper was still mostly intact. As Taylor notes, the heroine of The Song of the Lark, Thea Kronborg—an aspiring opera singer and stand-in for the young Cather—dreams of her destiny in a fictional evocation of that very same room: “From the time when she moved up into the wing, Thea began to live a double life. During the day, when the hours were full of tasks, she was one of the Kronborg children, but at night she was a different person.… She had an appointment to meet the rest of herself sometime, somewhere. It was moving to meet her and she was moving to meet it.”

In Rain Taxi, Allan Grabaud reviews a new translation of Joyce Mansour’s poems (Emerald Wounds: Selected Poems, translated by Emilie Moorhouse, July):

Included as well is Mansour’s take on gossipy female advice columns with some “Practical Advice While You Wait”; that is, for your man—when in a train station, a restaurant, a city hall, or at home. No matter being worried or jealous, the commandment is clear: The woman must stay “pretty, relaxed, sharp…” But don’t “wait in the streets” and always wait for the heart of the conflict steaming up “amongst the reddened leaves and the caramel fumes of your discriminations.”

Husband neglecting you? “Dowsing” has a cure: “Invite his mother to sleep in your room.” Want something more? Okay: “Piss in his soup when he lies down happily next to you.” And then, “Be gentle but skillful stuffing the fat goose / With octopus messages / And mandrake roots.”

In our sister publication in the City of Angels, James Palsey reviews Pip Adam’s The New Animals (2017), which prompted one reviewer to ask “What the fuck are we doing in this country when we are not reviewing and talking about this book?” [The country in question is New Zealand. What do they do there, anyway? Rugby? I hear it’s nice. —Steve]

Throughout the story, there is a clear divide between the generations. The older characters—whom we mostly learn about through Carla—are broke, tired, worn out, their bodies changing, morphing, aching in new places, while the younger generation, whom we mostly learn about through Tommy, are basically rich kids with time and options on their hands. They get to exercise to get stronger. Tommy’s dad is his investor, and Tommy’s granddad was his dad’s investor, yet Tommy believes those generations of wealth mean nothing, that he’s fighting the good fight, pushing against the old guard. Adam constantly uses the generational divide to examine social class. The two generations see everything differently. Even the way they feel, how they care about the world, is in conflict. While the older generation came of age in the 1990s, when “any kind of caring was frowned on,” the new generation cares “too much. They care crazily about things that no one gives a fuck about—or should. That was why they ran the world.”

In NLR, Dustin Illingworth reviews a pair of novels by Pasolini (Boys Alive, 1955, translated by Tim Parks, November 7; Theorem, 1968, translated by Stuart Hood, November 7) recently reissued by our cultural overlords at the NYRB:

The novel’s episodic structure—built loosely around criminal activity, family life, the procurement of prostitutes, group swims at the river, and plenty of shooting the shit—eludes a totalizing narrative. Scenes never outstay their welcome. A climax approaches, your heart lurches or breaks, and then you’re whisked to the next calamity a month or a year hence. It is in these pungent transitions that Pasolini betrays his obsession with cinema, in the way he weds his lyricism to setting, his prose like a camera eye, ever ready for the close up or tracking shot. Translator Tim Parks renders a lean, athletic prose that oscillates between beauty and brutality. Its wattage can’t be overstated. All is kinetic possibility, open-ended, chaotic, alive. No resolution, no hope, only action, action, action.

In The Atlantic, Tope Folarin reviews this year’s winner of the National Book Award for Fiction (Blackouts, by Justin Torres, October):

Much of Blackouts is a kind of Socratic dialogue between Juan and the narrator, yet instead of trading philosophical arguments in order to unearth essential truths, their principal mode of communication is storytelling. The stories that form the backbone of the novel are Juan’s sketches of Jan Gay. Juan reveals that it was Jan who initiated the Sex Variants report, and that she was subsequently erased from its history. The real Jan was already a published author when she started compiling the study, but she needed to secure the sponsorship of a group of scientists to help legitimize it. The group, which became the Committee for the Study of Sex Variants, eventually took over the project, nullifying her efforts. Jan’s experiences represent a kind of blackout; her identities—lesbian, female—seem to have prevented her from gaining the authorial credit she deserved. Juan eventually reveals that he knew Jan when he was a child, and supplements the archival material he has collected about her life with memories of the time he spent with her.

N.B.:

A. S. Byatt, scholar and novelist, died on Thursday. R.I.P.

The Point has a new advice column, “Higher Gossip: Problems in Sex and Love,” by Lillian Fishman. [Should we do an advice column? If you desire the advice of the Managing Editors on your problems, send them to washingreview@gmail.com. —Steve]

The Yale Review has a new column, “A Closer Look,” which will feature annotations of art or archival objects. In the first one, Anahid Nersessian on William Blake’s Laocoön: “Blake was also vehemently antiwar, and the resulting print, which expresses those sentiments, is uncannily contemporary, resembling a broadside or protest poster.”

The first issue of The Miami Native is out. [Andrew Boryga’s piece on writing a novel in Miami is a lot of fun. —Steve]

“Muriel Spark’s The Public Image from 1968 is 5 x 8 x 0.4 inches & 144 calculated pages.”

McSweeney’s is hiring interns.

Local:

On Sunday 18,000 people walked and ran across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge.

DC Zinefest 2023 will be held on the 5th floor of Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library today.

The Promised End, which “brilliantly weaves together the entirety of Giuseppe Verdi’s shattering Requiem, performed by eight exceptional vocal artists in a version that allows audiences to hear this music as if for the first time, and a one-woman monodrama depicting the composer Verdi, the play King Lear, and aged King Lear himself,” will be performed at the Source Theatre on dates from today to Sunday, December 10, and at the Baltimore Theater Project from Friday, December 15 to Sunday, December 17.

Poem:

“Soul” by David Ferry

What am I doing inside this old man’s body?

I feel like I’m the insides of a lobster,

All thought, and all digestion, and all pornographic

Inquiry, and getting about, and bewilderment,

And fear, avoidance of trouble, belief in what,

God knows, vague memories of friends, and what

They said last night, and seeing, outside of myself,

From here inside myself, my waving claws

Inconsequential, wavering, and my feelers

Preternatural, trembling, with their amazing

Troubling sensitively to threat;

And I’m aware of and embarrassed by my ways

Of getting around, and my protective shell.

Where is it that she I loved has gone to, as

This cold sea water’s washing over my back?

[Ferry, who passed last week, emerged later in his career as a notable poet and classical translator (his verse translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh is widely praised). This poem is from his 2012 Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations, which won the National Book Award.

I love how strange this poem is, both in its content and in its syntax. The syntax of the second of the three sentences in this poem is formidable—overwhelming, really, and yet handled with so much precision—and it’s interesting how it links the much simpler first and final sentences, both of which are questions that feel so troubled. What am I doing inside this old man’s body, and where is it that she I loved has gone to…? Both those lines are heartbreaking in their bewilderment. And I love that haunting tactile image we get in the final line. —Julia]

Upcoming book:

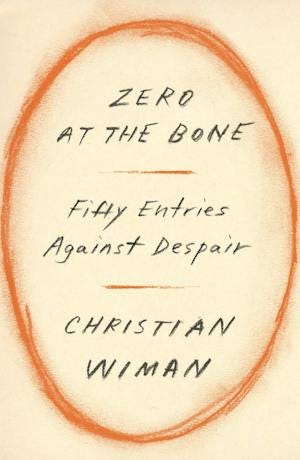

December 5 | FSG

Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair

by Christian Wiman

From the publisher: Zero at the Bone begins with Wiman’s preoccupation with despair, and through fifty brief pieces, he unravels its seductive appeal. The book is studded with the poetry and prose of writers who inhabit Wiman’s thoughts, and the voices of Wallace Stevens, Lucille Clifton, Emily Dickinson, and others join his own. At its heart and Wiman’s, however, are his family—his young children (who ask their own invaluable questions, like “Why are you a poet? I mean why?”), his wife, and those he grew up with in West Texas. Wiman is the rare thinker who takes up the mantle of our greatest mystics and does so with an honest, profound, and contemporary sensibility. Zero at the Bone is a revelation.

From an excerpt in Image: I begin this essay prompted by two things, a passage in C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce in which he talks of the necessity of drinking one’s particular shame to the dregs if one would ever be released from it. My shame is Christianity, sometimes. My shame is myself, sometimes. In any event I too often too-timidly sip of both, savoring my spite.

The second thing? As I read the Lewis passage, a hawk flew into my vision and landed on a tree limb I can see from my study. How we want the world to speak to us! But some utterance is too intrinsic to be speech. Some luck is love incompletely seen.