WRB—Nov. 25, 2023

Hot Dr. Pepper

Then said Evangelist, “If this be thy condition, why standest thou still?” He answered, “Because I know not whither to go.” Then he gave him the Washington Review of Books, and there was written within, Fly from the wrath to come.

Links:

Two from the newest issue of our sister publication on the Thames:

Patricia Lockwood went to Rome to meet the pope, who wanted to meet some artists [There are resonances with Grand Tour narratives in here. English audiences love nothing more than hearing about going to Italy and having weird experiences. —Steve]:

There now exist, in the world, several official photos where I appear to be cursing the pope in ermine language. As well as an image of his attempt to wrench his hand from mine, because when Ross stands and I walk forward to meet him, I glitch. I tell him my name, which seems untrue. “I hope your stomach feels better,” I say, insanely, pointing to mine. Possibly I even say tummy.

A bit of weather crosses the pope’s face. He’s mad at me, maybe, for not giving him a drawing called The Quantum Eternity of Love. No, he’s mad at me for not giving his hand back. He retrieves it, with surprising strength, and then raises two fingers and blesses my stomach. He is finally smiling—no longer trapped with the artists, but back with the bambini. Oh my God, I realize, as I walk back to my seat, he 100 per cent thinks I am pregnant.

Speaking of Grand Tour narratives, Clare Bucknell on Lord Byron:

“Deem” and “seem” form one of Byron’s favorite rhyming pairs. Deeming (judging, reckoning) is intimately connected to seeming because the claims to authority on which it grounds itself are questionable, illusionary, reliant on obfuscation or mystery. One important difference between Byron and Pope, the poet he most admired, is the degree of confidence each places in poetry’s ability to order the world. Mock-epic, a genre that gets its laughs from yoking high and low together, or making them switch places, “is right for Dryden and Pope,” Cronin argues, “because it is the mode that best registers confusions that they do not share.” It doesn’t work for Byron, who frequently advertises his confusions and distrusts those who claim a vantage point above them. Judging, as he presents it, is typically partial and autocratic, conducted by vengeful, inscrutable means: the “midnight carryings off and drownings,” “mysterious meetings, / And unknown dooms” that Marina, wife of the condemned Jacopo in The Two Foscari, laments; or, in English Bards, in a less desperate scenario, the merciless “sentences” handed down by the “tyrant” critics of the Edinburgh Review, a cabal of “Self-constituted Judge[s] of Poesy” only too eager to “decree the rack.”

[Are young men still trying to finish off Don Juan? I didn’t, personally, but after college I developed a plan for a similar mock-epic in ottava rima. I think I completed five stanzas. —Steve]

In Asterisk, D. Graham Burnett on the “alliance between psychologists and advertisers” that helped create modern advertising and the machinery they used to find out what people pay attention to:

This amazing ad represents a perfect little punctum in the world of midcentury attentional surveillance, a moment in which the scientific advertisers advertised scientific advertising as…an advertisement. Which is to say, what we have here is an ad for menswear that deploys the datasets developed by an actual eye tracker that had been developed in order to measure the attention value of advertisements!

We tend to think of eye tracking as a distinctly internet-age phenomenon, but in the 1930s such systems were in use—not just in sophisticated laboratories (where the devices could be used to study the “saccades” in human reading, or the optical reflexes under various forms of cuing and stimulations), but on Madison Avenue too, where they offered the promise of unprecedented access to the visual life of consumers.

In the Financial Times, Robert Armstrong on luxury clothing looking more and more like the cheap versions of the same product:

Witness, for example, the leisure sneaker phenomenon: you can buy a $1,000-ish pair from Loro Piana, or Louis Vuitton, or The Row, or Brunello Cucinelli, or Zegna. Beside their prices, what they all have in common is that they are not better looking, more refined, more comfortable or sturdier than a nice pair of Nike’s that will set you back less than $100 (manufacturing technology has driven the real cost of good sneakers down dramatically in recent years). The luxury sneakers do, however, successfully signal to a select group of people that you are rich.

The problem is that to a different select group of people, they signal that you are an idiot. The imperative to go casual has been taken as far as it can go, to the point where it makes a laughable contrast with the imperative to differentiate with price.

[I am well acquainted with this problem, having made my billions in the books and culture newsletter industry. —Steve]

Reviews:

In the local Post, becca rothfeld reviews a collection of Flaubert’s letters (The Letters of Gustave Flaubert, edited and translated by Francis Steegmuller, reissued September) [An Upcoming book in WRB—Sept. 23, 2023.]:

But the letters provide an even better refutation of Flaubert’s self-conception. Beginning when he is only 9 and ending when he dies of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 58, they are rife with autobiographical disclosures of the sort he sought to expunge from his fiction—and better yet, they reveal the extent to which all of his prose is permeated with his personality. “If style is the man, greatness of style is greatness of person,” the art critic and philosopher Arthur Danto wrote. It is hard to think of a statement Flaubert would have rejected more strenuously, but all the hallmarks of his fiction—the lightly mocking tone, the exacting eye for detail, the delight in incongruous juxtapositions of high and low—are present in the letters from the very first line.

[I read Sentimental Education last month and discussed my impressions in WRB—Oct. 18, 2023. —Steve]

In Bookforum, Justin Taylor reviews “Lexi Freiman’s satire about influencers, AntiFa, and the love of literature” (The Book of Ayn, November 14):

Literature is a difficult genre to neatly define, but you could do worse than start with Anna’s own notion of “a natural and necessary thinking-through-of-things.” Next, maybe look to Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up, where he asserts the value of being able “to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Anna, of course, is defining jokes, and Fitzgerald “the test of a first-rate intelligence,” but I still feel like we’re getting somewhere. A work of literature should serve as an intellectual proving ground for both author and reader (otherwise we might as well be watching television) and all the best books are at least a little funny. This one is very funny. But I hope the generous quote given above demonstrates that it isn’t just funny. Freiman is a gifted stylist, part of a tradition that is traceable from forebears such as Martin Amis, Sam Lipsyte, Lorrie Moore, and NW-era Zadie Smith, to fellow travelers like Andrew Martin, Tony Tulathimutte, Alissa Nutting, and Patricia Lockwood. Freiman’s sentences are swift and vivid, her paragraphs precision machines. Even her goofiest set pieces and illest-advised riffs feel propulsive and pull their share of narrative weight. The Book of Ayn, like Inappropriation before it, finds genuine pathos and imaginative empathy in the absolute last places you’d think to look for them or, frankly, hope to find them. Lexi Freiman shitposts from the bottom of her heart.

In the Journal, J. Ryan Stradal reviews a cookbook of the Midwest (Midwestern Food: A Chef's Guide to the Surprising History of a Great American Cuisine, with More Than 100 Tasty Recipes, by Paul Fehribach, September):

Unlike some chefs, who throw would-be home cooks into the deep end, Mr. Fehribach often makes concessions to his readers’ skill, time and budget constraints. He explains methods by which recipes could be made easier or more cost effective while still presenting the best approach as he sees them. In the recipe for green-bean casserole, for instance, he writes: “I’m not going to denounce anyone who decides to make this casserole exactly according to Campbell’s original recipe, although I do think it’s possible to develop a deeper flavor by substituting Quick Cream of Mushroom Soup and using Worcestershire sauce instead of the soy sauce.” Later in the same recipe, he explains that “French’s french-fried onions are hard to improve on, unless you want to create a long, extra step of prepping, dredging, and frying onions.…So we’re going to embrace a bit of our Midwestern heritage and use a processed ingredient from the dry-goods shelf at the supermarket.” Such antisnobbery is perhaps the marrow of Midwesterness and appears here in manifold ways.

N.B.:

Hope you all enjoyed a steaming cup of hot Dr. Pepper this Thanksgiving! [Chris says: “This is fine.” I was drinking New England cider, as the Pilgrims intended. —Steve]

The Library of America is having a sale on boxed sets.

Fernando Sdrigotti wants to “make self-publishing great again.”

New issues:

LRB Vol. 45 No. 23 · 30 November 2023 [As linked to above.]

European Review of Books Issue Four

Granta 165: Deutschland

One Thing is a new newsletter that “collects things that are cool and good.” [Cool and good are cool and good things for a thing to be. —Steve]

Poem:

“Elegy for N. N.” by Czesław Miłosz, translated by Miłosz and Lawrence Davis

Tell me if it is too far for you.

You could have run over the small waves of the Baltic

and past the fields of Denmark, past a beech wood

could have turned towards the ocean, and there, very soon

Labrador, white at this season.

And if you, who dreamed about a lonely island,

were frightened of cities and of lights flashing along the highway

you had a path straight through the wilderness

over blue-black, melting waters, with tracks of deer and caribou

as far as the Sierra and abandoned gold mines.

The Sacramento River could have led you

between hills overgrown with prickly oaks.

Then just a eucalyptus grove, and you had found me.True, when the manzanita is in bloom

and the bay is clear on spring mornings

I think reluctantly of the house between the lakes

and of nets drawn in beneath the Lithuanian sky.

The bath cabin where you used to leave your dress

has changed forever into an abstract crystal.

Honey-like the darkness is there, near the veranda

and funny young owls, and the scent of leather.How could one live then, I really do not know.

Styles and dresses flicker, indistinct,

not self-sufficient, tending towards a finale.

Does it matter that we long for things as they are in themselves?The knowledge of fiery years has scorched the horses standing

at the forge,

the little columns in the market place,

the wooden stairs and the wig of Mama Fliegeltaub.We learned so much, this you know well:

how, gradually, what could not be taken away

is taken. People, countrysides.

And the heart does not die when one thinks it should,

we smile, there is tea and bread on the table.

And only remorse that we did not love

the poor ashes in Sachsenhausen

with absolute love, beyond human power.You got used to new, wet winters,

to a villa where the blood of the German owner

was washed from the wall, and he never returned.

I too accepted what was possible, cities and countries.

One cannot step twice into the same lake

on rotting alder leaves,

breaking a narrow sunstreak.Guilt, yours and mine? Not a great guilt.

Secrets, yours and mine? Not great secrets.

Not when the bind the jaw with a kerchief, put a little cross

between the fingers,

and somewhere a dog barks, and the first star flares up.No, not because it was too far

did you not visit me that day or night.

From year to year it grows in us until it takes hold,

I understood it as you did: indifference.

[This poem, written in 1962, is from Miłosz’s New and Collected Poems, 1931-2001.

I love the way that distance is communicated in that first stanza. Between the first line (Tell me if it is far for you) and the last line of that stanza (and you had found me), we get a kind of route map that the departed beloved has to follow to reach the speaker. It’s rich with details that, by their variety, reinforce the sense of distance (the blue-black, melting waters, lights flashing along the highway, beech wood and prickly oak). All those lines detailing place also physically separate the speaker’s initial command (Tell me) from the moment of theoretical union (you had found me), creating a parallel between the poem’s structure and its content.

There’s so many images here that I love, too. One of my favorites is the transformation we get via the syntax in One cannot step twice into the same lake / on rotting alder leaves, / breaking a narrow sunstreak, which takes Heraclitus’s famous phrase and makes it stranger. The reason this can’t be done, in Miłosz’s retelling, is not the water’s movement, but rather the rotting alder leaves and the breaking of a narrow sunstreak.

Beyond physical distance, the poem also deals with the distance created by memory. The bath cabin where you used to leave your dress / has changed forever into an abstract crystal. Things that were once intimate, shared experiences slowly transform into abstractions that, though they may still hold great beauty, cannot be touched. Does it matter, Miłosz asks, that we long for things as they are in themselves? (This line reminded me a bit of the Glück poem we featured a couple weeks ago.) The poem seems to view it as inevitable that we come to be separated from our loves as they are in themselves: gradually, what could not be taken away / is taken. So how much does it matter, then, that we long for something that we can’t have? The poem doesn’t seem to give a clear answer one way or another. On one hand, there’s that final admission that what really kept the speaker and N. N. apart during life was their mutual indifference. And yet the poem itself can’t maintain its indifference; moments of confusion, or wrestling, like the heart does not die when one thinks it should seem to show that our speaker can’t let go of the sense that all this does, somehow, matter. And there’s the remorse that we did not love…with absolute love, beyond human power. Of course that’s an impossible task, to love absolutely beyond human power, and yet, despite the indifference, the individual failures, even the beloved’s death, the speaker can’t stop trying to close the gap of distance. —Julia]

Upcoming book:

December 12 | Slant

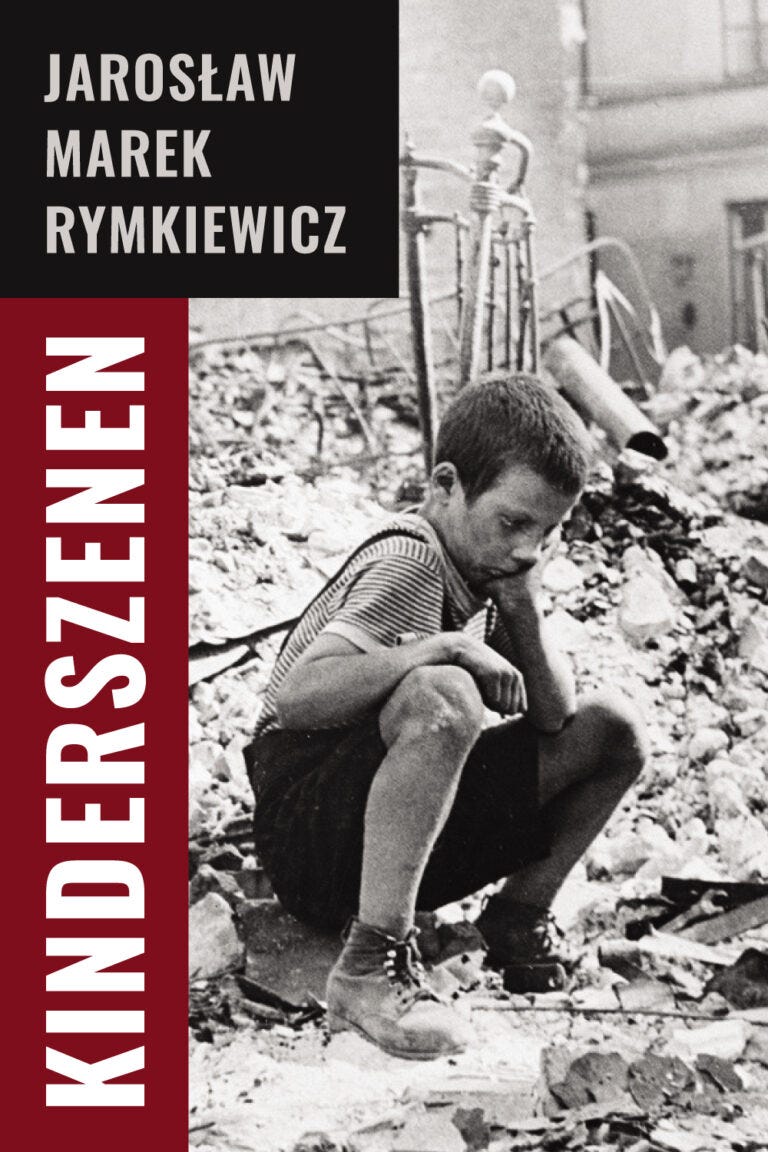

Kinderszenen

Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz, translated by Charles S. Kraszewski

From the publisher: An old man—poet, playwright, essayist, and scholar—sifts through the broken fragments of his memory as he recounts what it was like to grow up in Warsaw during the German occupation of World War II. The result is Kinderszenen, a searing and controversial memoir by a major post-war Polish writer that has evoked both debate and praise, now translated into English for the first time.

The book’s title comes from the suite of piano pieces by Robert Schumann which evoke the innocence and joy of childhood—thus providing a wrenching counterpoint to the violence, destruction, and madness that characterize Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz’s coming of age.

While the scenes of his youth are depicted in vivid detail, from his boyish encounters with cats, horses, and turtles up to the shocking brutality of murder and mayhem witnessed at first hand, what really sets Kinderszenen apart is its extended meditation on the nature of war, oppression, and fanatical nationalism, and the possibility—however doomed it may seem—of human resistance to those forces. Here is an enduring testimony that remains starkly relevant to our own time.