WRB—Nov. 9, 2024

“FIFTY THOUSAND DOLLARS FOR THAT BOOK!”

George Washington gave his name to Washington, D.C., but the Managing Editors of the Washington Review of Books defined it.

N.B.:

Save the Date: The next WRB Presents will be on November 12 at Sudhouse D.C., featuring Ralph Hubbell, Johannes Lichtman, Mikra Namani, and Danuta Hinc.

Next month’s salon will meet on the evening of November 30 to discuss the topic, “Is order more important than justice?” If you would like to attend, please please email Chris for the details.

Links:

In Aeon, Abigail Tulenko on ornament in Austen and Darwin:

The two also share a concern with the philosophically rich relationship between the natural world and aesthetic beauty. Darwin was fascinated by capricious ornamentation—natural features such as the peacock’s plumes, which seemed to serve no other purpose but beauty, even to the detriment of other sorts of biologic fitness. He saw a paradox: the naturalist posits that all that exists can be explained in natural terms. And, yet, there is a sense in which ornament, in its superfluity, goes beyond what nature dictates. How can the naturalist make sense of “excessive” beauty, of nature’s “wonderful extreme,” which may appear to defy or transcend the closed logic of the naturalistic worldview?

Austen prefigures Darwin’s contention that aesthetic ornamentation is a natural human practice that places us in continuity with the wider natural world. Like Darwin, she grapples with ornament’s apparent superfluity, and the tension between naturalism and aesthetic “excess.” She writes evocatively of this clash in Pride and Prejudice: “I shall never forget her appearance this morning. She really looked almost wild,” gossips Mrs. Hurst after Elizabeth traipses across dirty fields to see her ill sister. Worst of all: “her petticoat; I hope you saw her petticoat, six inches deep in mud, I am absolutely certain.” The aesthetic is literally drenched in the natural; human ornament splashed with mud.

[The little dispute between Mrs. Gardiner and Elizabeth about whether to visit Pemberley goes as follows:

“My love, should not you like to see a place of which you have heard so much?” said her aunt. “A place, too, with which so many of your acquaintance are connected. Wickham passed all his youth there, you know.”

Elizabeth was distressed. She felt that she had no business at Pemberley, and was obliged to assume a disinclination for seeing it. She must own that she was tired of great houses: after going over so many, she really had no pleasure in fine carpets or satin curtains.

Mrs. Gardiner abused her stupidity. “If it were merely a fine house richly furnished,” said she, “I should not care about it myself; but the grounds are delightful. They have some of the finest woods in the country.”

The appeal of the house is not the house itself but its integration into the natural world around it. —Steve]

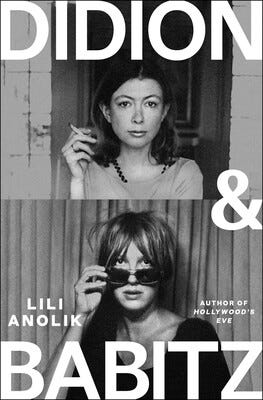

In the Journal, an excerpt from Lili Anolik’s book about Didion and Babitz (Didion & Babitz, November 12) [Today’s Upcoming book.]:

Hollywood’s appeal for Joan and Dunne wasn’t hard to fathom. It was one of the few places on earth where a writer could strike it rich. And writing movies for the money and only the money seemed to be how a writer maintained his or her integrity. At least in the eyes of other writers. “[Joan and John] didn’t give a shit about the movies except it was a way to make a lot of money,” said novelist Dan Wakefield. “And I totally respect that.” In brief, books were art, movies were commerce.

Only, that was changing.

In 1969, the summer of Manson, Easy Rider roared onto screens trailing clouds of motorcycle exhaust and marijuana smoke. A new era of Hollywood had begun. (“Now the children of Dylan were in control,” actor-screenwriter Buck Henry told me.) It was Nouvelle Vague American style. And Joan and Dunne, in their house on the bluff above Nicholas Beach, overlooking the houses of actresses Jennifer Salt and Margot Kidder, of producers Michael and Julia Phillips, were smack-dab in the middle of it. Though I don’t think they quite knew what “it” was.

[The sportswriters wish they were doing politics, the politics writers wish they were doing sports, the literary types wish they were doing movies, the movie types wish they were doing something more literary, no one has ever been satisfied in this life, and so on. —Steve]

In The Nation, Francesca Billington interviews Claire Bishop about technology in museums and performance venues:

Billington: How have the formal strategies of artists changed in relation to the changes in attention span we are seeing?

Bishop: It’s happening in various ways, some conscious, some not. I think all artists today anticipate how the exhibition is going to look in a photograph. Then, on the level of a work, there are different responses, some of which I argue are symptoms rather than deliberate attempts to engage critically with attention as a problem. On the one hand, you have the rise of interest in performance, especially durational performance. This is a direct effect of media technology like smartphones. There’s a desire for immediate experience, being together with a group of people. But it’s also paradoxical: The physical immediacy of performance also looks great in photographs. It’s a symptom as well as the cure.

On the other hand, you have artists making installations that contain a lot of dense materials—perhaps in reaction to the one-line concision of social media and headlines. But the effect is to compound the viewer’s sense of information overload. So it cuts both ways: A dense, intellectualized, text-based installation is both a counter to and a symptom of our information environment. The book doesn’t deal with the “experience” economy, the rise of all those immersive installations like the Chagall Experience and the Van Gogh Experience. I’m concerned primarily with work that appears in museums, biennials, and galleries.

[I’m going to have the WRB painted onto the side of buildings. Look on my dense, intellectualized, text-based installation, ye mighty, and despair! I am also registering my usual objection to “information overload” talk—you know you can stop looking at the screen, right? In fact, you should only look at the screen to read the WRB. Even better, print it out and read it with you daily (print) paper. —Steve]

In The Hobbyhorse, david c. porter on the development of a Beckett teleplay:

They all love to talk about Dante—well, not all of them, really, but enough to constitute a trend. When you pull up a scholarly text on Samuel Beckett’s Quadrat 1+2, his limit-pushing 1981 teleplay “for four players, light and percussion”, it will more likely than not mention, with the slightly-smug eagerness of a child sharing a fact they believe to be, maybe, just a bit naughty, that said players, who do nothing but move along the edges and through the middle of a square of empty stage, only ever turn to the left—just like (and here is the part where your eyebrows are supposed to rise a hair in measured appreciation of the Implications so deftly implied) the damned in Dante’s Inferno. It is a common enough recurrence to inspire Graley Herren to drolly quip, following a brief review of the extant Quadrat literature, “If constantly turning to the left were all it took to constitute a Dantean allusion, then the entire NASCAR circuit would qualify as one big Inferno.”

In the Financial Times, Ariella Budick on Belle da Costa Greene, who managed J. P. Morgan’s library:

Belle and her brother added a hint of Portuguese to explain their darker complexions. Armed with that new identity, Belle da Costa Greene plunged into the heart of whiteness. She got her first job in the library at Princeton, which wouldn’t (knowingly) accept Black undergraduates until 1947. There, she met Junius Spencer Morgan II, who introduced her to his uncle, J. P.

Greene became the patriarch’s personal librarian in 1905, when the architects at McKim, Mead and White were still putting the finishing touches on the limestone palazzo on East 36th Street. Six years later she scored her most famous acquisition: Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, printed by William Caxton in 1485 and extant in only a single complete copy. Morgan, willing to pay up to $100,000 for this rarity, was thrilled that Greene snagged it for half that sum. It seemed like a lot to everyone else: “FIFTY THOUSAND DOLLARS FOR THAT BOOK!” crowed a headline in The World Magazine, embellished by drawings and photographs of the star librarian in her feathered hat.

[What’s wrong with America is the lack of star librarians in feathered hats. —Steve]

Reviews:

In The New Statesman, Lucy Hughes-Hallett reviews a book about the political legacy of Paradise Lost (What in Me Is Dark: The Revolutionary Afterlife of Paradise Lost, by Orlando Reade, December 10):

Reade traces Milton’s influence on subsequent canonical authors, but this book is not primarily about literary history. The biggest story that Reade is telling is that of slavery. He notes that Milton introduces the theme early, when Beelzebub asks why God hasn’t killed all the rebel angels, and concludes it is so that they can “do him mightier service as his thralls.” The angels-turned-devils are slaves, doing God’s “errands in the gloomy deep.” Reade traces that theme of enslavement through a succession of authors and political activists.

The line begins with Olaudah Equiano. Equiano was abducted from his home in West Africa and sold into slavery. After years of hard labor, he bought his freedom, and in 1789 he published his autobiography. Writing about the notoriously cruel slave-plantations of Montserrat, Equiano quotes Milton on Hell. The island is the place where “Hope never comes / That comes to all, but torture without end.” Equiano doesn’t name his source: perhaps he didn’t want people to think he was comparing enslaved people like himself with devils.

[Regular readers of the WRB will know that 2024 is the Year of Milton. Not everything about Milton’s post-Restoration work is about finding a new way forward now that the political dream is dead, but phrasing Beelzebub’s question as “why hasn’t God killed all the rebel angels?” brings that problem to the front, especially since Milton went into hiding after the Restoration. (Campbell and Corns make a solid case in their biography of him that he was very unlikely to be executed, but he couldn’t have known that at the time.) The dream is dead—what now? At the beginning, the devils ask that question; at the end, Adam and Eve do. —Steve]

In our sister publication out West, Annie Berke reviews Elizabeth Strout’s new novel (Tell Me Everything, September):

It’s funny because it’s strange. Literary fiction has dabbled in crossovers, but nowhere near as often as blockbuster franchises, comics, or genre fiction. Strout’s books consistently articulate bewilderment around and disapproval of mass culture; even theatrical performances are suspect. In Olive, Again (2019), the estrangement between a long-married couple is dramatized through their separate television sets. In Anything Is Possible (2017), a grandfather is confronted, Dickens-style, by the actor who plays Ebenezer Scrooge in the town’s annual production of A Christmas Carol. In both cases, the patriarchs are thrown by these adaptive forms and devices into literal shock, even life-threatening medical crises. No one keels over reading Proust, so let’s just say it’s not a ringing endorsement for the boob tube or even the hokey community playhouse.

Strout diplomatically referred to HBO’s 2014 adaptation of her Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Olive Kitteridge (2008) as “its own thing,” a comment meant less as a criticism than an expression of how her sense of creative ownership fell away while watching. For their part, critics described it as mostly faithful, as well-received adaptations usually are. After all, the character of Olive, an aging schoolteacher who looms large but feels invisible, was born for the screen: blunt and argumentative, she’s a Frances McDormand type for whose portrayal McDormand won an Emmy. It’s easy to picture her, a tall, unshrinking woman in every sense—but this is also because Strout writes about her in a sharp, omniscient third person.

In the local Post, Anthony Domestico reviews a book on mysticism (Mysticism, by Simon Critchley, October) [An Upcoming book in WRB—Oct. 26, 2024; we linked to an excerpt in WRB—Aug. 14, 2024.]:

Precision matters, especially when talking about things that frustrate precision. Meister Eckhart sought a different kind of ecstasy than the Stooges did. Critchley knows this, of course, but his wide angle of vision risks dissolving into mistiness. He writes of Julian of Norwich: “The ambition of her writing is to show how the self can somehow lift itself from woe to wellness, from sin to salvation.” Yet as a Christian, Julian believed that God’s grace, not her own self, did the lifting. Critchley writes that mysticism “might permit us to push back against the violent pressure of reality and allow a richness of life and a possible transfiguration of self and the world.” But mysticism doesn’t claim to push back against reality. It claims to reveal reality, to allow us to see how things are if only we had eyes to see.

N.B. (cont.):

A discovery of early Christian tombs in Egypt.

An investigation into how checked baggage gets lost.

Local:

Nic on Dumbarton Oaks:

How little has changed from 1809 to now! Though the area in Northwest D.C. near Dumbarton Oaks is heavily populated, the interests of its inhabitants remain much the same—money, food, and gossip.

[The WRB does its best. —Steve]

Lux Choir is performing William Byrd’s Mass for Five Voices at St. Jerome Catholic Church in Hyattsville on Thursday, November 14 at 8 p.m.

Poem:

“Affirmation” by Donald Hall

To grow old is to lose everything.

Aging, everybody knows it.

Even when we are young,

we glimpse it sometimes, and nod our heads

when a grandfather dies.

Then we row for years on the midsummer

pond, ignorant and content. But a marriage,

that began without harm, scatters

into debris on the shore,

and a friend from school drops

cold on a rocky strand.

If a new love carries us

past middle age, our wife will die

at her strongest and most beautiful.

New women come and go. All go.

The pretty lover who announces

that she is temporary

is temporary. The bold woman,

middle-aged against our old age,

sinks under an anxiety she cannot withstand.

Another friend of decades estranges himself

in words that pollute thirty years.

Let us stifle under mud at the pond’s edge

and affirm that it is fitting

and delicious to lose everything.

[I hate to hand it to the state of New Hampshire, but sometimes I have to.

There’s so much water imagery in this poem— “row,” “pond,” “shore,” “strand,” sinks,” “pond’s edge”—that I almost expect a Catullus 70 reference with the pretty lover, but things are so impermanent here that she won’t even tell you otherwise. The final image parallels Canto 6 of the Inferno, where the gluttons for their punishment lie unmoving in the mud. It’s not a pleasant image, but Hall holds it out as a possibility; at some point you will lose everything, so would you like to make your peace with it now or later? And there is an acuity to “delicious.” I can’t tell you why but it’s the right word. —Steve]

Upcoming books:

Scribner | November 12

Didion & Babitz

by Lili Anolik

From the publisher: 7406 Franklin Avenue was the making of one great American writer: Joan Didion, a mystery behind her dark glasses and cool expression; an enigma inside her storied marriage to John Gregory Dunne, their union as tortured as it was enduring. 7406 Franklin Avenue was the breaking and then the remaking—and thus the true making—of another great American writer: Eve Babitz, goddaughter of Igor Stravinsky, nude of Marcel Duchamp, consort of Jim Morrison (among many, many others), a woman who burned so hot she finally almost burned herself alive. Didion and Babitz formed a complicated alliance, a friendship that went bad, amity turning to enmity.

Didion, in spite of her confessional style, is so little known or understood. She’s remained opaque, elusive. Until now.

With deftness and skill, journalist Lili Anolik uses Babitz, Babitz’s brilliance of observation, Babitz’s incisive intelligence, and, most of all, Babitz’s diary-like letters—letters found in those sealed boxes, letters so intimate you don’t read them so much as breathe them—as the key to unlocking Didion.

What we’re reading:

Steve is still reading The Historical Novel. He also read Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents That Forged the Republic by Lindsay M. Chervinsky (September). [If you have unabridged print copies of A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America or (especially) the Discourses on Davila please send them to me. I’m going to figure this thing out. —Steve]

Critical notes:

BDM on being a fake fan:

The internet changes the game slightly. I’m constantly challenging myself with tests that prove that I am a fake ___ girl about all kinds of stuff. This is probably at least a little healthy—or at least, better than the alternative, of pretending to an expertise you do not in fact possess—but it’s also definitely stupid too, to act as if at any moment a troll will appear and say, like, if a fan you truly be, name to me their albums three.

But if I’d happened to see a picture of Yva’s in a magazine in the nineties or something, clipped it out perhaps, it would have made sense to say I was a fan without really much experience or knowledge. And then there are things where that is still basically the case—like paintings. If a painter’s body of work is scattered across several museums in different countries, you’ll probably only see a handful of them in person. But I think it would still make sense to say “my favorite painter is Sargent” even if you’d never seen a Sargent painting and only seen reproductions.

On the other hand, and this is also very odd, it’s never really felt like people know less, or are less willing to go and look up something that they don’t know, even though it’s genuinely never been easier to encounter an unknown phrase and simply look it up.

[I think of something else BDM wrote a year ago (quoted in WRB—Dec. 20, 2023): “Prestige writing often means assuming an audience that is somehow very cultured and totally ignorant at the same time.” “Cultured” is a question of pose and “ignorant” a question of knowledge. What to do about people who won’t look up things they don’t know, though, is a harder question. I think, at least, we can stop writing phrases like “the twentieth-century painter Mark Rothko.” —Steve]

Isn’t it curious that the Swedes and Norwegians have ended up as the arbiters of world culture? It’s a good trick. In the fifth book of the Aeneid, the titular hero does not participate in the funeral games for Anchises; he merely presides. In this way also the Roman emperors did not participate in the cursus honorum, but oversaw it. Americans, Chinese, Germans, Indians all sweating away in the bowels of the machine of history while the people behind ABBA and modular furniture dole out approbations. I don’t know what lessons are to be learned from this, other than that the Nordics are surprisingly slippery operators.

Small things. Memories of connection. Why of all things would I remember a moment of sharing agreeable sentences with a man, a stranger, sixteen years ago in a suburb of Buffalo, where we set up a Juicy Couture mall store for minimum wage? Because it’s beautiful and it lives. As we unpacked and sorted endless boxes of denim product we began to talk of the same memories—how football and all sports had drastically changed. He was about fifteen years older, but we related: “Remember when Walter Payton scored a touchdown? No celebration and he just tossed the ball back to the ref. Today, nobody does that.” Then we laughed and nodded, happy to have this small moment shared. And I’ve had that with other men—remembering how sports used to be. Brief encounters that buoyed. We looked at each other with something like happiness and then we never saw each other again. I felt as close to them as I’ve felt to almost anyone. How? Why? So I could remember it now when it’s needed most.

[I think that one of the great advantages of being old will be the ability to harangue recalcitrant youths with stories of watching Brady and Mahomes on the field and Belichick and Saban on the sideline. The game, as we all know, was at its best when you specifically were young, and it’s only gone downhill since then. It’s nostalgia, but in the service of something you rarely see in America—the wisdom of age defining itself in those terms: “I have been around long enough to see more of this game than you have, and with that comes a knowledge of the game that you lack.” It’s also about keeping a memory alive. When Gerke had this conversation Payton was dead. (There was a very nice story on his final days and his friendship with his fullback, Matt Suhey, in The Athletic a couple weeks ago.) But he taught something about the game and how it should be played (literally and metaphorically), and for that he is worthy to be talked about in the way that we talk about anyone who passed down tradition to us. “Today, nobody does that”—how easily we forget. —Steve]