WRB—Oct. 11, 2025

“now-expected dynamics”

What should they know of the Washington Review of Books who only the Washington Review of Books know?

Links:

In Liberties, Ryan Ruby on Wu Jingzi’s Rulin Waishi, or The Unofficial History of the Scholars and canon wars:

Disillusioned by the corruption of scholarship, a motley crew forms. This group of failed candidates is made up of talented refuseniks and independent men of letters in Nanjing, and led by Wu’s “romantic” alter ego Tu and his friend Chuang Shao-Kuang, who has just declined the Emperor’s offer of a ministerial post thanks to a timely intervention by a scorpion that crawls into his scholar’s cap. The group decides to create a counter-institution called the Tai Po Temple. Chapter Thirty-Seven, which is about the temple’s dedication ceremony, is unanimously held to be the central episode of The Scholars, the one that gives structural and in all respects from the other chapters, including its form, whose “rhetoric of repetition” and “schematic expository style,” in the words of Shang Wei, the Du Family Professor of Chinese Literature and Culture at Columbia University, are pastiches of the ancient ritual manuals that were objects of great interest in Wu’s circle in Nanjing. Wu catalogues the ritual’s seventy-six participants, led by the virtuous Dr. Yu as master of sacrifice, in a manner reminiscent of the catalogue of ships in the Iliad; he describes their rites of purification and ceremonial dress; he details the decorations put up in the temple, the various items sacrificed to the ancient sage Tai Po, and the period-specific musical instruments played to entertain his spirit; finally, he gives a blow-by-blow account of the ritual itself. By recreating this Confucian-era practice of ceremony and music, the participants hope to help “produce some genuine scholars, who will serve the government well.”

Confucius in the Analects (translated by James Legge):

If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music will not flourish. When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded. When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires, is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect.

Hugh Kenner:

Again and again in the Cantos single details merely prove that something lies inside the domain of the possible. It is not necessary to prove that the possibility was ever widely actualized; only that it exists. . . . The Cantos scan the past for possibilities, but their dynamic is turned toward the future.

[Perhaps both the scholars recreating Confucian-era practice and the Cantos are insufficiently attentive towards the conditions which allowed things to exist, but, as Ruby says in the next paragraph, “Critique of the present is just as often legitimized by an appeal to an idealized past as it is legitimized by an appeal to an imagined future.” In recreating the ritual the scholars are not only appealing to an idealized past; they are denying that it is the past at all by making it part of the present. —Steve]

Reviews:

In The Yale Review, Sloane Crosley reviews a collection of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s writing about drinking (On Booze, 2011, reissued November 4):

In “My Lost City,” booze is more prominent as a catalyst for discontent. Fitzgerald becomes disillusioned with “the style and glitter of New York even above its own valuation.” Through “many an alcoholic mist,” he stumbles between “lush and liquid garden parties,” getting “roaring, weeping drunk” on his last penny. He returns to St. Paul for three years, and when he comes back, he finds that nights out in New York have become untenable. The pace of the city has quickened, and the size of the parties has expanded. “The morals were looser,” he writes, “and the liquor was cheaper.” Here, drinking is part of a larger problem, just as it was once part of a larger joy. In a rich twist, Fitzgerald decides his friends drink too much. He hightails it to France. When he returns to Manhattan yet again, his judgment of nightlife (“a last hollow survival from the days of carnival”) is sharper than ever. The city “no longer whispers of fantastic success and eternal youth.” Frankly, as a New Yorker, I am tempted to wash my hands of this Goodbye to All That urtext. Patient: Doctor, it hurts when I do this! Doctor: Then don’t do that. But “My Lost City” remains a gorgeous topography of an emotional hangover, charted by one of our most cherished cartographers.

[Fitzgerald’s protagonists and narrators are rarely having fun; they instead assume everyone else in any given glittering world is having fun but them. That other people might also not be having fun rarely occurs to them, frequently because their tendency to think of themselves as the protagonist of reality does not lend itself to serious consideration of the inner lives of others. Fitzgerald is doing something similar here. It may be true that he learned something about himself through attending New York cocktail parties over the span of a decade, but I suspect that the purpose of those cocktail parties was not the edification of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The reader can only wish for Fitzgerald’s sake that there had been some kind of “New York Cocktail Parties Are Decadent and Depraved” moment—”we came down here to see this teddible scene: people all pissed out of their minds and vomiting on themselves and all that . . . and now, you know what? It’s us.” (Not as if it helped Hunter S. Thompson.) —Steve]

In The Guardian, Philip Terry reviews Seamus Heaney’s collected poems (The Poems of Seamus Heaney, edited by Rosie Lavan and Bernard O’Donoghue with Matthew Hollis, November 18):

What impresses is the consistency and the variety, coupled with the continuing ability to surprise us, for while Heaney always hugs the shore of tradition, he is not afraid to experiment, developing and deepening his craft. In an interview with Dennis O’Driscoll, discussing the attention he pays to the sounds of words in Wintering Out (1972), Heaney was dismissive when asked about the sound poets Kurt Schwitters and Bob Cobbing, pronouncing: “I have nothing at all to declare in that area.” Yet when I corresponded with Heaney in 2006 about experiments in French poetry, including the formal innovations of the Oulipo, he responded with enthusiasm. The French tradition of syllabic poetry, where syllable takes precedence over stress patterns, informs the slithering six-syllable lines of “Beyond Sargasso,” one of many poems about eels, in Door into the Dark (1969). Heaney’s love of a pun is pushed to the limit with chilling effect in “Two Lorries,” his only sestina, which reinvents the form by metamorphosing the end word “load” into “lode”, “lead”, “payload”, and finally “explode”. In Seeing Things (1991) Heaney creates a form of his own invention in the clarifying 12-liners of the sequence Squarings (1991), a form he was to return to again and again, where he attains a new simplicity and transparency, almost stripped of rhetoric, as the skin is stripped from an eel: “Roof it again. Batten down. Dig in. / Drink out of tin. Know the scullery cold, / A latch, a door-bar, forged tongs and a grate.”

[I wonder if while working on “Two Lorries” Heaney had been listening to Dylan, whose “Visions of Johanna” has this in its final verse:

And Madonna, she still has not showed

We see this empty cage now corrode

Where her cape of the stage once had flowed

The fiddler, he now steps to the road

He writes, everything’s been returned which was owed

On the back of the fish truck that loads

While my conscience explodes

Beyond the rhyme of “loads” and “explodes” it also shares with Heaney’s poem a mother who belongs to an earlier time and a truck. (Here, by the way, is a picture from 1985 with both Dylan and Heaney in it featuring some incredible outfits.) —Steve]

In 4Columns, Jessi Jezewska Stevens reviews Claire-Louise Bennett’s latest novel (Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, October 21):

Unlike the stark gender- and age-based asymmetry that critics such as Noor Qasim and Namwali Serpell have noted as a hallmark of contemporary romance—novels marked by legislative malaise, negotiations of power, female self-harm, and heteropessimism—in Bennett’s latest, these now-expected dynamics go slack. The age difference is stretched to such an extreme that Xavier is flawed, but undeniably vulnerable. As a result, the question of who has exploited whom, and of how to treat one another in love (or heartbreak), becomes an open one, even if its answers remain painful and ambiguous.

[Chris and I discussed an instance of Serpell’s argument in WRB—Jan. 20, 2024.

Once you notice “heteropessimism”—a terrible word but it’s apparently the one we’re using—you start seeing it far beyond contemporary romance. A friend recently pointed out to me that the cultural moment around female friendship this millennium tends to offer it as a substitute for romance with men, which is still theoretically the goal but ends up unsatisfying due to whatever is wrong with men these days. (Do not write in to tell me what is wrong with men these days.) And some of the central pieces of this cultural moment are very explicit about this substitution—Frances Ha (2012), for example. —Steve]

In The New Statesman, Nikhil Krishnan reviews a history of opera in Britain over the last century (Someone Else’s Music: Opera and the British, by Alexandra Wilson, July):

Wilson has brisk and persuasive responses to those who accuse opera of elitism. Elitist how? Is it the price? Tickets to a Taylor Swift concert are more expensive by an order of magnitude; the cheapest seats at both Covent Garden and the [English National Opera] sell out the fastest. And a ticket to watch touring companies or a performance at a regional theatre is unlikely to set you back more than a cinema ticket. Moreover, productions at Covent Garden are broadcast live at cinemas across the country.

Is it that the rich are more frequently to be found at the opera? But they are more frequently found at everything: restaurants, gyms, football matches. Is it that the opera is full of bejewelled prima donnas? But operatic superstars are rare—your typical singer would be lucky to be earning the national median wage.

Are operas “unrelatable”? “No more than James Bond, and often less.” Is it that their conventions are arcane? Well, so are those of cricket. Is it that operas are generally in foreign languages? With the advent of surtitles, that makes them no harder to access than Squid Game or Shogun. Is it the off-putting people in dinner jackets and tiaras? But with the partial exception of Glyndebourne in the summer, black tie is rare at the opera, and often the choice of people who treat it as a harmless bit of fancy-dress for a night out.

[Krishnan gets off one of the funnier lines I’ve read in a while near the end: “I had advantages: for an Indian, there was nothing the tiniest bit off-putting or elitist about a form of entertainment that went on for three hours and in which the characters broke into song at every opportunity.” I’m not sure how well “Opera: it’s basically Bollywood” would work to promote it, but someone should try. —Steve]

In the local Post, becca rothfeld reviews a memoir of package delivery (I Deliver Parcels in Beijing, by Hu Anyan, translated from the Chinese by Jack Hargreaves, October 28):

Yet he managed to find something to savor in even the most fatiguing and dispiriting work. “The simpler the labor, the more easily I feel positively motivated by it, because I can very directly see the value it brings to others,” he reflects. “When I handed over a parcel to a customer, I could see the satisfaction and excitement in their expression.” He is even capable of appreciating the aggravating customer who refused to open a door manually and insisted on pressing the unreliable automatic opening button until it worked. “It’s a relief there still exist certain values in this world that transcend the utilitarian rules of gain and loss we’ve long placed our faith in,” he muses. The customer’s insistence on inefficiency struck him as a beautiful anachronism.

[As one of the world’s last letter-writers—as always, write more letters, support the boys in blue (employees of the United States Postal Service)—I sympathize with the desire to preserve beautiful inefficiencies, but I do not think automatic doors fall into that category. If anything, the customer’s behavior smacks of laziness, demanding that technology do something that he could do on his own very easily. The beautiful anachronisms worth preserving are craft traditions that preserve and pass down a specific kind of human skill and artistry. And while I suppose this customer may push a button with a refined and exquisite beauty beyond the comprehension of my unimaginative mind, somehow I doubt it. —Steve]

N.B.:

Congratulations to László Krasznahorkai on winning the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Some previously unknown music by Henry Purcell was discovered. [“Remember me, but ah! forget my song written for a character named ‘Monsieur le Prate.’” —Steve]

Revolutionary War reenactors in the northeast. [I wondered, so I counted: if this appeared in The New Yorker there would be 76 diaereses in it, 74 for forms of “reenact” and two for forms of “coordinate.” —Steve]

New variations in the martini. [My opinion on the martini is that you’re just pouring a bunch of gin into a glass, so you might as well embrace that. —Steve]

What people are doing in Beijing’s “fake offices.”

“Consumer research revealed that 42% of people didn’t know Lay’s chips are made out of real potatoes.” [This aggression against the potato farmers of the County will not stand. —Steve]

New issues:

Liberties Volume 6 - Number 1 | Fall 2025 [As linked to above.]

Literary Review of Canada November 2025

Poem:

“Sequel” by Alice Fulton

The universe’s ignorance of me is privacy.

I know the endangered meadow in a way

it will never know itself.Must be the cosmos wanted something

to hear the splendornote

and find the fossil data,to take an interest

in extinction events and ask

what pulsation is thisexserted from, what What.

I don’t know about purpose,

the why of whywe’re here, but we seem to witness

with a difference.

To think is to exercisegodheat. Haven’t I been given

everything, my life?

I might as well revisethe opening to read

the universe adores me.

It leans. It likes. It feelsno one could fail in quite

the same way as I’ve.

It gives burnishwhen what is worthy of it.

The cosmos must have wanted something

to provide ovationand disdain and inquire

under whose auspices

comes applause and hissand ask whose modulations unscroll

in flowers so immoderate that many

fewer would be none the lessa form of excess.

[This poem contends with contradiction: Fulton’s assertion of what she knows, counterposed against what she does not. First, the lovely, “I know the endangered meadow in a way / it will never know itself,” followed by, “I don’t know about purpose, / the why of why // we’re here, but we seem to witness / with a difference.” But it is the metanarrative moment that seems to me to be the fundamental element upon which the rest of the poem depends: “I might as well revise / the opening to read / the universe adores me.” It is a pivot which, by relocating Fulton in her work, balances the intensity and awe otherwise found throughout. —K. T.]

Upcoming books:

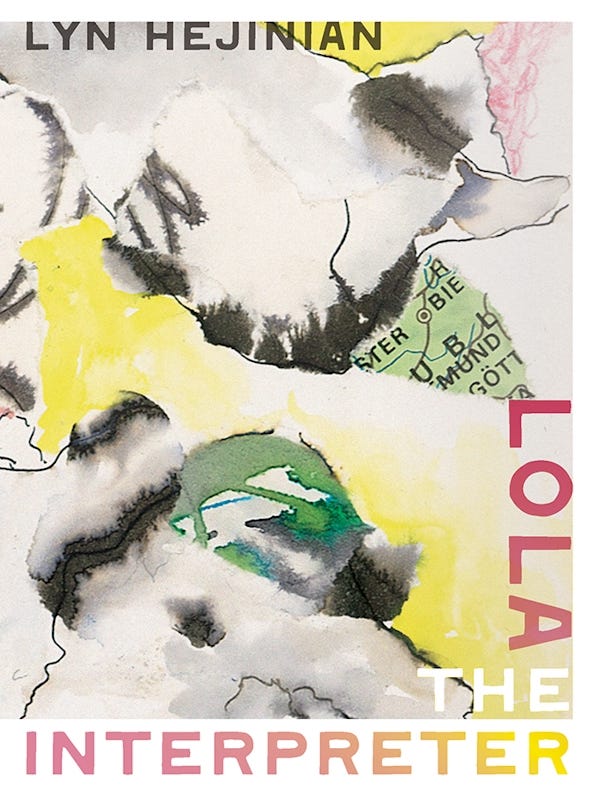

Wesleyan University Press | October 14

Lola the Interpreter

by Lyn Hejinian

From the publisher: Lyn Hejinian’s Lola the Interpreter is a prose poem in which an “I” and a series of quasi-characters (including Lola) interpret one another, their quotidian lives, and the terms, categories, and presuppositions that allow fragments of experience to be extracted from the flux of perception and framed as objects of analysis. This work stands as a culmination of Hejinian’s lifelong exploration of thought’s infrastructure, threading through her oeuvre from A Thought is the Bride of What Thinking to My Life (1976) and A Border Comedy (2001), to this, her last book. What perhaps marks Lola as a work of late style, of new experimentalism even at the twilight of Hejinian’s life, is the extent to which the interpretation that at first seems to be generated out of discrete events transcends its ostensible occasion and becomes philosophy more broadly, a philosophy poised between a necessary skepticism toward the given or imposed and a life-affirming commitment to the emergent possibilities within the ever-shifting and uncertain domain of daily existence.

Also out Tuesday:

Archipelago Books: The Leucothea Dialogues by Cesare Pavese, translated from Italian by Minna Zallman Proctor

Atlantic Monthly Press: Unabridged: The Thrill of (and Threat to) the Modern Dictionary by Stefan Fatsis

Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster: Joyride: A Memoir by Susan Orlean

Pantheon: True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen by Lance Richardson

Yale University Press: Philip Roth: Stung by Life by Steven J. Zipperstein

What we’re reading:

Steve is still reading The Faerie Queene.

Critical notes:

Victoria Moul on Ben Jonson’s poetry of friendship:

Jonson puts an Horatian tag at the center of the poem. Roe survived unscathed “His often change of clime (though not of mind).” The quotation from Horace Epistles 1.11 to which this alludes is still quite well-known, and would certainly have been instantly recognizable, even slightly hackneyed, in the early seventeenth century: caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt (“men who rush across the sea change the weather, not their heart”). Jonson uses the reference to tell us that Roe’s traveling, by contrast, was not out of some desire to escape himself or his character: it delicately implies a kind of wisdom and consistency.

I think it works in other ways as well. It takes us away from the epigram—conventionally addressed or at least imagined as addressed, to someone present before us—and to an epistle, by definition an address to someone who is not there. It is part of the pathos of the poem that this epistle cannot reach its addressee. But Jonson’s little poem reworks Horace’s epistle in another way too. Horace’s poem to Bullatius ends by assuring him that if one has a “balanced mind” (animus . . . aequus) then everything you seek—all the secrets of “living well”—are to be found here, there or anywhere, wherever you happen to be.

[Poetry about friendship is difficult. Love poetry we’ve worked out, but friendship doesn’t have as many models in poetry. The elegy can quickly move away from the dead to the fascinations of the living—“Lycidas” is infamous here, but even something as deeply felt as In Memoriam A. H. H. moves around to a number of Tennyson’s interests beyond his friend Arthur Hallam. Epistolary poems are not really about friendship per se—they could be, but friendship is outward-facing enough that it doesn’t promote that sort of reflection, and so the poems (when not merely display pieces reworking tropes) tend to be more of a snapshot of a moment in a friendship than about a friend or friendship in itself. The best poem I know about a friendship is E. A. Robinson’s “Isaac and Archibald,” which is about fictional characters and whose speaker merely observes the friendship between the titular men. He is also a boy, and Isaac and Archibald are old men who spend a decent portion of the poem telling him that he doesn’t know what it’s like to be old. This message underlines that some portion of their friendship is opaque to him; he will never quite experience the precise way theirs works. “All men, in the vertiginous moment of coitus, are the same man” is not quite true, but all lovers think they understand all other lovers, hence the unending pileup of clichés ever ancient, ever new. Friendship is different.

The best poems about specific friendships, I think, are dedications because the question “why am I dedicating this to you?” forces a more explicit reckoning with what makes the friendship special (at least as it involves the thing being dedicated). And it has to be communicated in a manner consistent with the rest of the friendship. For example, the combination of Catullus 1’s sincere affection for and slight teasing of Cornelius—sincere affection conveyed through teasing—reveals, I think, how that friendship tended to play out. —Steve]