WRB—Oct. 22, 2022

“After a page you are obfuscated by the literary debauch.”

[The subject line of this email comes from an essay by Charles J. Finger in The Dearborn Independent in 1925. He was worked up about Gertrude Stein’s “If You Had Three Husbands,” which just arrived in the mail (though I do not remember ordering it) from Sublunary Editions in their neat little issue with Finger’s essay appended. —Chris]

To do list:

Follow us on Twitter, and consider whether you would like to apply to be the new, perhaps better-managing social media intern (email us a pitch for yourself at washingreview@gmail.com!);

order a tote bag or now a MUG, both of which receive rave reviews and are as functional as they are stylish;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, now stored on this page for non-paying readers to access, either by placing or responding to one;

and,

Links:

A great essay in Artforum by Chloe Wyma on Elsa Schiaparelli: “Born in 1890, Schiaparelli was indebted to an earlier generation’s exoticizing, incense-scented bohemianism, a sensibility inherited as much from her own family of learned and cultured Roman aristocrats as from Mariano Fortuny or her mentor Paul Poiret. An astronomer uncle discovered what he insisted were Martian-built canals on the surface of the red planet; an Egyptologist cousin discovered the tomb of Nefertiti; her father was a gentleman scholar, specializing in the medieval Islamic world. But Schiaparelli wasn’t stuck in the past, or in ‘the East.’ The New Yorker’s Paris correspondent Janet Flanner (who wrote under the pen name ‘Genêt’) attributed her international success to the distinctly ‘un-European modernity of her silhouettes, their special applicability to a background of square shouldered skyscrapers, of mechanics in private life, and pastimes devoted to gadgetry.’” [My immediate association is the passed-around Schiaparelli dress in The Girls of Slender Means. —Nic]

Kristin Czarnecki writes from the Neglected Books blog about Sigrid Unset’s 1911 debut novel, Jenny.

“This pleasure is apparent in all of the Cruise-starring Mission: Impossible features. Taken together, they coalesce into a bricolage celebration of spectacular human engineering and the spirits of the age that spawned them. Running across St Paul’s Cathedral, speeding around the Arc de Triomphe, or abseiling a modern feat like the Burj Khalifa, Cruise wants you to look and to feel the vestiges and continuations of Geist. But also look at him, a seeker looking to conjoin with that trans-historic spirit through trial and turmoil, a vision of modern-day transcendence achieved through alignment with the past.” Notes from David Garry Hughes on current questions in cinema.

For 4Columns, Hannah Black writes about a new exhibition of Diane Arbus: “Photography is in fact something super traditional for Arbus: a mortification of the hubris of painting. As a young artist she was admired by her family and teachers as a promising painter, her talent carefully cultivated in progressive schools. But she believed her paintings to be in some way lifeless because they were purely the creation of her imagination. Like the world of her youth, the paintings’ very proficiency offered up only the image of a bloated self-regard. She needed to make a hole, an aperture.”

Twilight Zone and John’s Apocalypse at The Paris Review. [Setup to a terrible joke, sounds like. —Chris]

Reviews:

If you somehow haven’t seen it already, John Jeremiah Sullivan resurfaces with a review of The Passenger and Stella Maris: “The Passenger is far from McCarthy’s finest work, but that’s because he has had the nerve to push himself into new places, at the age of all-but-90. He has tried something in these novels that he’d never done before: I don’t mean writing a woman (although there’s that), but writing normal people. Granted, these normal people are achingly good-looking and some of the smartest people in the world and they speak in lines, but they are not mythic. Or they are mythic but not entirely so. They have childhoods and stunted or truncated adulthoods. They go to restaurants and bars and visit their friends. I think those may have been my favorite parts.”

Another in the Times: Jennifer Szalai reviews critic Peter Brooks new bromide against “stories” out from NYRB last week (Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative, October): ““This ‘storification of reality’ or ‘hyperinflation of story’ is so widespread that Brooks says he can’t even open a package of cookies without encountering some corporate pablum announcing itself as ‘Our Story.’ Such an example may seem trivial, but he argues that our “mindless valorization of storytelling” makes us more susceptible to those with more malevolent intentions—‘inertly accepting the notion that all is story, and that the best story wins.’”

For the Cleveland Review of Books, Tiber Worth reviews Emily Ogden’s volume of essays from earlier this year (On Not Knowing: How to Love and Other Essays, April): “On Not Knowing, by contrast, is nothing if not enlivening. There is palpable joy on every one of these pages: the joys of life, literature, and thought. The subtitle—How to Love and Other Essays—might seem presumptuous (or ironic) at the bookstore, but after reading, its aptness becomes apparent. Love, or intimacy, is the subject of Ogden’s work, just as much when she is writing about Melville and Hardwick as when she is writing about sex, marriage, or motherhood.” [Longtime readers may remember that we linked to Ogden’s conversation with the LARB in May. —Chris]

Two on Leo Damrosch’s recent book about Casanova (Adventurer: The Life and Times of Giacomo Casanova, May). He’s an interesting case!

For Harpers, Clare Bucknell: “The link he makes between mobility and a kind of magical thinking makes sense in the context of his feelings about traditional authority. Though skeptical by nature, he thrived, as Damrosch argues, in ancien régime milieus: he depended on hierarchies because they gave him something to scale, and on rules because, without them, there would be nothing to break.”

And for The New Criterion, Pat Rogers: “But who were adventurers, historically, in the English sense, and should Casanova be regarded as the archetypal member of this tribe? Damrosch writes that they formed ‘a true subculture, which overlapped with other subcultures that were important in Casanova’s story but have not been adequately explored by other biographers.’ Among the attributes of the subject that he lists, there is gambling, but also interest in the occult, libertinism, efforts to borrow ideas from Enlightenment philosophy, and—most apposite of all—restlessness. These are certainly defining characteristics of the breed, but not peculiar to it, and other men (and women) exemplified some of the characteristics more precisely. Further on, Damrosch remarks that his hero was about to encounter ‘the shadowy underclass to which [he] himself would soon belong.’ It’s doubtful whether there was an actual subculture in the way of a tightly connected milieu of the like-minded, as in the art world of late-nineteenth-century Paris or the hippie community of Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s. Nevertheless, a looser international grouping can be discerned, even if the participants were defined by actions rather than beliefs, and would never have agreed about very much.”

For Fare Forward, Marda Messick reviews Louise Glück’s tiny, weird new book (Marigold and Rose: A Fiction, October): “Glück’s ‘a fiction’ is exactly like that. Marigold and Rose are not only fictional; they are not remotely plausible. Real babies (Emmy and Lizzy, for example) don’t develop self-awareness until months past their first year. But Glück’s twins are parabolic. Their overheard thoughts provoke questions about what is true and real for our own existence. It is oddly as if Mother had given birth to triplets, and we are the third baby, a reminder that ‘unless you change and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.’”

N.B.:

Rest in peace, Peter Schjeldahl.

Book Sections are so back, says Ann Kjellberg. [Interesting here: “current paper shortages are actually attributed, in part, to what turned out to be unwarranted pessimism in American paper manufactury about the death of the physical book” —Chris]

Purse Book is a weekly newsletter about reading hot little books & being a gal on the go.

Upcoming book:

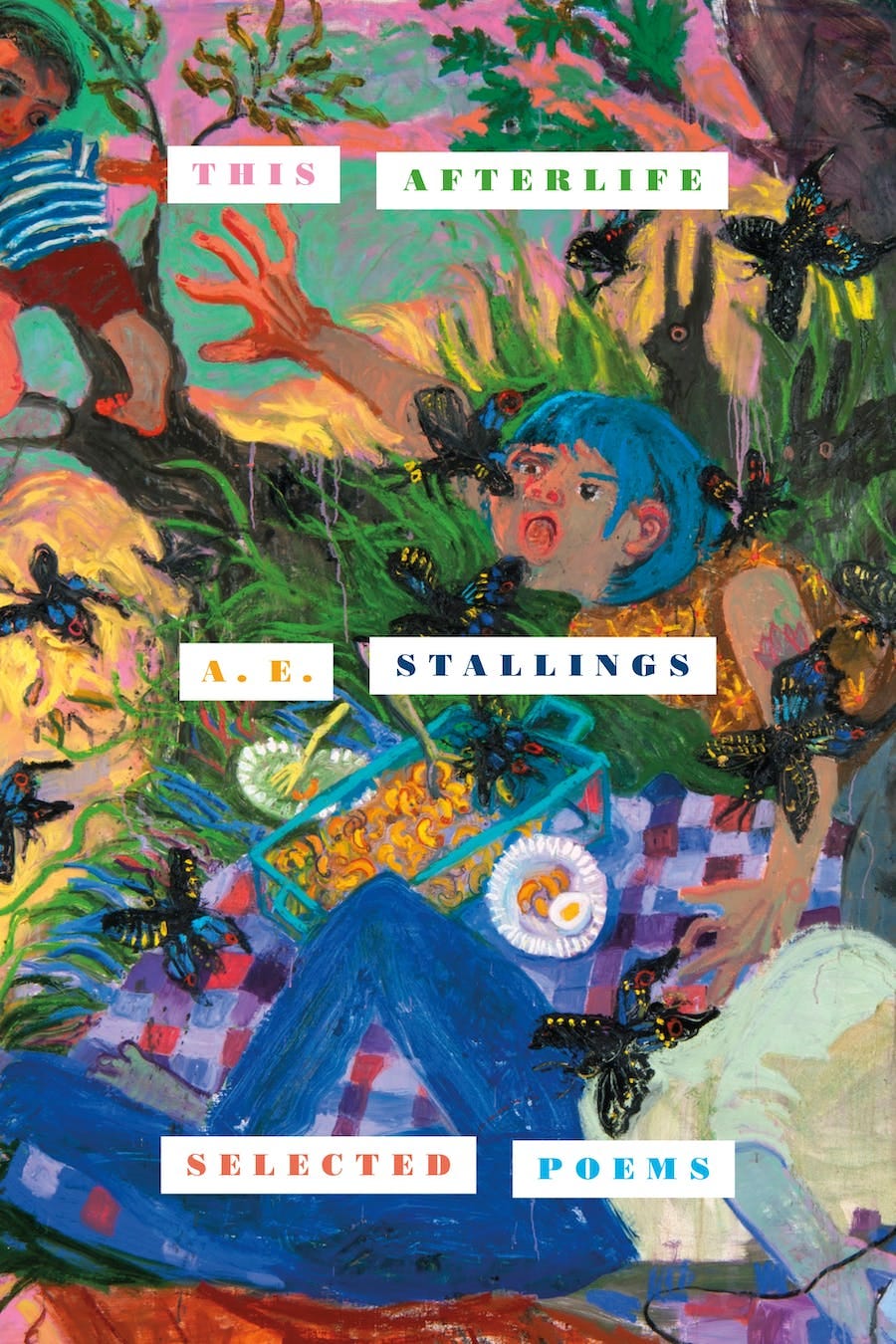

December 6 | FSG

This Afterlife: Selected Poems

by A. E. Stallings

From the publisher: This Afterlife: Selected Poems brings together poetry from A. E. Stallings’s four acclaimed collections, Archaic Smile, Hapax, Olives, and Like, as well as a lagniappe of outlier poems. Over time, themes and characters reappear, speaking to one another across years and experience, creating a complex music of harmony, dissonance, and counterpoint. The Underworld and the Afterlife, ancient history and the archaeology of the here and now, all slant rhyme with one another. Many of these poems unfold in the mytho-domestic sphere, through the eyes of Penelope or Pandora, Alice in Wonderland or the poet herself. Fulfilling the promise of the energy and sprezzatura of Stallings’s earliest collection, her later technical accomplishments rise to meet the richness of lived experience: of marriage and motherhood, of a life lived in another language and country, of aging and mortality. Her chosen home of Greece adds layers of urgency to her fascination with Greek mythology; living in an epicenter of contemporary crises means current events and ancient history are always rubbing shoulders in her poems.

Expert at traditional received forms, Stallings is also a poet of restless experiment, in cat’s-cradle rhyme schemes, nonce stanzas, supple free verse, thematic variation, and metaphysical conceits. The pleasure of these poems, fierce and witty, melancholy and wise, lies in a timeless precision that will outlast the fickleness of fashion.