WRB—Oct. 25, 2025

“an unbeloved cousin”

As flies to wanton boys, is the Managing Editor of the WRB to the gods,—

They kill him for their sport.

Links:

In The Baffler, Sean Hooks interviews Ilya Gridneff and Helen DeWitt about their new book (Your Name Here, October 28) [The Upcoming book in WRB—Oct. 22, 2025.]. DeWitt:

As for the novel, the original idea was to have emails from an “Ilya” interacting with an affectless, alienated, bestselling writer, Rachel Zozanian, a character shaped by Tom McCarthy’s Remainder (2005) and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s schizophrenic from Anti-Oedipus (1972). Agents complained that the Zozanian character was not “fleshed out” and that they had no idea where it was going. The point was to get quick cash so Ilya could get time for his own book, so I couldn’t ignore them, though “fleshing out” was an unspeakable departure from the Remainder vibe and missed the point that “Ilya” was meant to be the joker in the pack, gloriously disruptive of narrative direction and control. I thought (tragic irony) that this could be fixed by making clear that the disruption was intentional.

If we appropriated Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler (1979)—that is, with multiple interrupted texts and a second-person narrator—but took it even further with multiple second-person narrators, and if we spelled out the debt to Kaufman and Spike Jonze’s Adaptation (2002)—that is, the impossibility of imposing virtuous order, with arguments between authors a part of the narrative—then intention would be clear and all would be well. Your Name Here is possibly a more interesting text now but was fatal as a fast track to that clinking-clanking sound.

Henry Oliver on slavery in Mansfield Park:

“Unquestionably,” says [Marilyn] Butler, “Austen expects us to see the play as a step in Maria Bertram’s road to ruin.” Maria is not too much subject to Sir Thomas’ supreme authority, but too little. He chose her husband, but ignored her moral development. By participating in the theatricals, Maria was allowing herself to act on feelings over which she ought to have exercised self-command.

The wayward Bertram children cannot be saved by the staging or not staging of an illicit romance, nor by Edmund’s reasonable objections; instead, they ought fundamentally to be more like Fanny: they require moral education, the one great theme of all Austen’s work. Mansfield Park may be a place of some subjugation (it is, still, ultimately hierarchical), but it is also a place of individual moral failure. (As ever, Austen points to the parents as the problem. Lady Bertram is so indolent she is no sort of mother.)

It is this that links the slavery parts of the novel to the whole.

[While Sir Thomas opposes the play, his opposition fails to prevent it from happening not only because he has been inattentive to the moral development of his children; more directly, it happens because he is not there to stop it from happening. The estate of a great English landowner under absentee management is a site of moral ruin that its owner would prefer not to think about. There are obvious differences, yes, but does this not also apply to the plantations in the Caribbean that are also the property of these great English landowners?

And the last we hear of Julia Bertram is this:

She had been allowing [Mr. Yates’] attentions some time, but with very little idea of ever accepting him; and had not her sister’s conduct burst forth as it did, and her increased dread of her father and of home, on that event, imagining its certain consequence to herself would be greater severity and restraint, made her hastily resolve on avoiding such immediate horrors at all risks, it is probable that Mr. Yates would never have succeeded. She had not eloped with any worse feelings than those of selfish alarm. It had appeared to her the only thing to be done. Maria’s guilt had induced Julia’s folly.

Whether her imaginings would have been right, or whether her father would have shown himself to be a changed man, is hard to say. But her fears show how Sir Thomas’ authority has been understood by someone formed by it and still subject to it. No doubt Sir Thomas did not intend this to be the result of his parenting, but this is what his daughter thinks of his authority: it is authority for authority’s sake, and punishment for punishment’s. It is aimed at instilling fear and not love, and it acts as if frightening someone into behaving is an adequate substitute for giving them a moral education. And so she runs away. As before, I admit that there are obvious differences, but is this not one form of relationship Sir Thomas has with some of those under his authority leaching into another? —Steve]

In The New Criterion, John P. Rossi on Dwight Macdonald:

For sheer vitriol, Macdonald’s review—really a demolition job—of Colin Wilson’s The Outsider (1956) outshone anything he had to say about By Love Possessed (1957). Cozzens was a serious writer, though a flawed one in Macdonald’s opinion. He saw Wilson as an “earnest, humorless, and self-confident” young man who wrote one of those weighty books that fall from the presses every year, discussing the big questions facing man: in Wilson’s case, the sense that some major figures in history are “Outsiders”—T. E. Lawrence, Van Gogh, Nietzsche, et al. Wilson describes his archetype as follows: “The Outsider is a man who is awakened to chaos . . . the only man who knows he is sick in a civilization that doesn’t know it is sick.”

The critic, however, has no time for Wilson’s dive into cultural or intellectual history. He finds the analysis “crude” and “banal” and written in a prose he calls debased and lacking in vigor and exactitude. What really seems to bother Macdonald, though, is how the literary world fell for what he believed was a clear example of his “[Masscult and Midcult”] argument: a piece of bad middlebrow trash being passed off as high culture by critics who should know better.

[Earlier Rossi says that “Masscult and Midcult” “has passed from the literary scene and is rarely discussed today.” It’s true that nobody is saying “Masscult” and “Midcult,” but, as Rossi does, people say “middlebrow” for the latter, and Macdonald’s essay is occasionally discussed in that connection. If it has faded from memory it’s only because the entire concept of “brows” no longer makes much sense—I discussed the disappearance of highbrow, and what has replaced it, at some length in WRB—Sept. 27, 2025. —Steve]

Reviews:

In our sister publication in Tinseltown, Amy R. Wong reviews a book about Chinese history and King Lear (The Chinese Tragedy of King Lear, by Nan Z. Da, June) [An Upcoming book in WRB—June 7, 2025.]:

A demand for filial piety in the form of exaggeration and flattery—love that must be expressed as propaganda—is what gets the tragedy of Lear going, and what gets the tragedy of Maoism going too. For generations of Lear’s readers, the opening scene of the play is the first outrageous instance of its overall improbability (according to literary scholar A. C. Bradley, something in the play’s “very essence [ . . . ] is at war with the senses”). Why does Lear need a pro forma public proclamation from his daughters of their love if he already intends beforehand to divide the kingdom three ways? Why does Cordelia refuse to humor what could simply be an aging parent’s petulant bid for exaggeration? Why would Lear subsequently react so disproportionately out of hand as to disown Cordelia for her measured declaration of love and banish Kent for his reasonable plea for the king to “check [his] hideous rashness”? How does the intensity of the violence to follow get going so quickly after what seems, on the surface, like a mere ceremonial formality for a peaceful transfer of power?

[It never occurred to me that Lear’s behavior was anything particularly improbable. I have known elderly people who, I assume to cope with the loss of agency and ability that comes with aging, became ever more difficult and demanding, more insistent on displays of loyalty and affection, more paranoid that their family and friends were somehow out to get them, and more willing to cut people out of their lives for small slights. And if someone with that temperament were in a position of political power it is not hard to see how it could corrode politics for the same reasons it corrodes a family. (The answer to “Why does Cordelia refuse to humor what could simply be an aging parent’s petulant bid for exaggeration?”, by the way, is “Because this is the thousandth time he’s done something like this, and she can’t take it anymore.”) —Steve]

In The Nation, Barry Schwabsky reviews a collection of T. J. Clark’s criticism (Those Passions: On Art and Politics, March):

Art historians often want to see artists as typical of their time and place while still proclaiming the significance of their creations, without quite coming to terms with the paradox of finding exaltation in the ordinary. It reminds me of the complaint about certain kinds of writing made by one of the characters in William Gaddis’ great novel The Recognitions (1955): “It never takes your breath away, telling you things you already know . . . as though the terms and the time, and the nature and the movements of everything were secrets of the same magnitude.” Clark, every so often, really can take your breath away, precisely because he is attuned to the strange contradictions art so often generates. In writing about the eighteenth-century painter Jacques-Louis David, that revolutionary whose classicism would exert such a conservative influence on French painting, Clark expresses the paradox by acknowledging that “David’s painting is of its time” but only in its way of being “deeply absorbed in dreaming an other to the present.”

[Perhaps the last days of the ancien régime, and then revolutionary and Napoleonic France, were particularly suited for dreaming an other to the present, but everybody has always done this. David would be neither the first nor the last to discover the rhetorical force of invoking the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome as a contrast to the dismaying present. That David’s ideas of an alternative world are filtered through his classicism is one thing that does make him of his time. (And we can discuss the influences, both personal and cultural, that would have led David in that direction, as well as the specific ways ideas and images from classical antiquity would have been useful to the revolutionary project David participated in.) Many people in the back half of the eighteenth century spent a lot of time thinking about classical antiquity as a model for a new world, though, and very few of them were David. —Steve]

N.B.:

A history of motels.

A history of the tuba.

“‘Space Tornadoes’ Could Cause Geomagnetic Storms” [Seems like an oversight that there is not a great ’70s hard rock song called “Space Tornadoes.” Maybe parts of “Space Truckin’” live could be said to depict space tornadoes as the space truckers make their way through space Oklahoma. —Steve]

New issues:

Harper’s Magazine November 2025

The New Criterion Volume 44, Number 3 / November 2025 [As linked to above.]

Poem:

“A Hunger So Honed” by Tracy K. Smith

Driving home late through town

He woke me for a deer in the road,

The light smudge of it fragile in the distance,

Free in a way that made me ashamed for our flesh—

His hand on my hand, even the weight

Of our voices not speaking.

I watched a long time

And a long time after we were too far to see,

Told myself I still saw it nosing the shrubs,

All phantom and shadow, so silent

It must have seemed I hadn’t wakened,

But passed into a deeper, more cogent state—

The mind a dark city, a disappearing,

A handkerchief

Swallowed by a fist.

I thought of the animal’s mouth

And the hunger entrusted it. A hunger

So honed the green leaves merely maintain it.

We want so much,

When perhaps we live best

In the spaces between loves,

That unconscious roving,

The heart its own rough animal.

Unfettered.

The second time,

There were two that faced us a moment

The way deer will in their Greek perfection,

As though we were just some offering

The night had delivered.

They disappeared between two houses,

And we drove on, our own limbs

Sloppy after that, our need for one another

Greedy, weak.

[When Smith wakes to the sight of the deer she feels, “Free in a way that made me ashamed of our flesh— / His hand on my hand, even the weight.” And later, in the wake of the second sighting—“we drove on, our own limbs / Sloppy after that, our need for one another / Greedy, weak.” The deer and the rawness of desire join together at the center of the poem: “I thought of the animal’s mouth / And the hunger entrusted it. A hunger / So honed the green leaves merely maintain it.” Though I’ve read this poem several times now and I have yet to reach a definite conclusion about the relationship between the deer and the allusions to the body, but I think it is neatly embodied in the phrase “the heart its own rough animal.” —K. T.]

Upcoming books:

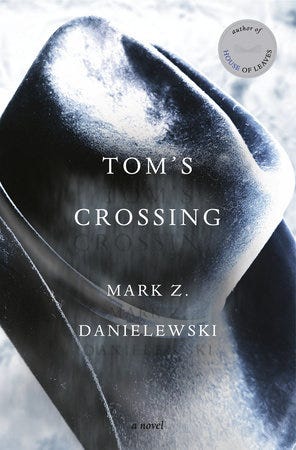

Pantheon | October 28

Tom’s Crossing: A Novel

by Mark Z. Danielewski

From the publisher: While folks still like to focus on the crimes that shocked the small city of Orvop, Utah, back in the fall of 1982, not to mention the trials that followed, far more remember the adventure that took place beyond municipal lines.

For sure no one expected the dead to rise, but they did. No one expected the mountain to fall either, but it did. No one expected an act of courage so great, and likewise so appalling, that it still staggers the heart and mind of anyone who knows anything about the Katanogos massif, to say nothing of Pillars Meadow.

As one Orvop high school teacher described that extraordinary feat just days before she died, Fer sure no one expected Kalin March to look Old Porch in the eye and tell him: You get what you deserve when you ride with cowards.

Also out Tuesday:

Astra House: I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan, translated from the Chinese by Jack Hargreaves [We linked to a review in WRB—Oct. 11, 2025.]

Farrar, Straus and Giroux: When All the Men Wore Hats: Susan Cheever on the Stories of John Cheever by Susan Cheever

Penguin Press: Dead and Alive: Essays by Zadie Smith

PublicAffairs: Chaim Soutine: Genius, Obsession, and a Dramatic Life in Art by Celeste Marcus

Slant Books: Invited to the Feast: Poems by Bonnie Naradzay

What we’re reading:

Steve read Forward Progress: The Definitive Guide to the Future of College Football by Bill Connelly (September). [Connelly is one of the rare “stat guys” with great insight about the sport as a whole because he has done the reading. Fans, coaches, administrators, and media tend to have the memories and attention spans of goldfish, but Connelly traces back the issues of the day through the past hundred years because college football has been fighting about the same things for a long time. And, if you want to know where something is going, it is useful to know where it is and how it got there.

As always, the lessons of college football extend beyond college football, and Connelly’s best chapter is not really about the sport. Instead, it focuses on other sports that have seen declines in popularity (boxing, baseball, and NASCAR get the most time) and derives from their stories lessons that college football should heed. Needless to say college football is currently doing the opposite of heeding them. The stories all go something like this: the people in charge of a sport wanted to make more money, either directly, as in the case of boxing moving to pay-per-view or strikes and lockouts in baseball, or indirectly, as in NASCAR leaving many of its traditional Southern racetracks in pursuit of more casual fans in other parts of the country. And if any of this alienated hardcore fans by removing things they loved about the sport, so what? They’d always be there. That’s what “hardcore fan” means, after all. But it doesn’t always work that way, as Connelly says:

You can put your hardcores through hell, but you probably shouldn’t change what’s most important to them, even if it means sacrificing some short-term growth. And you won’t find out if you’ve driven them away until the casuals have ditched you and you need them more than ever.

This is not a new story; the goose that laid the golden eggs is one of Aesop’s fables. But it is also a story of today. Degrading the experience of your existing customers in the pursuit of new ones, whose experience you will degrade in turn because this cycle of degradation leads to more and more revenue, is more or less Cory Doctorow’s concept of “enshittification.” (I will say that “enshittification” is a word I despise because it embodies the very thing it aims to describe and condemn, but no matter.) When Doctorow came up with the idea he was not thinking about sports. He was thinking about Big Tech. But in a world where Amazon Prime has Thursday Night Football, Apple TV+ has Friday Night Baseball, and Netflix has WWE RAW, is it any surprise that the attitudes of one are seeping into the other?

The joy of observing college football as a “cultural critic” (and not as a fan) is in part that nobody is in charge of college football, and the different powers that fight to direct it are all, more or less and each in their own ways, self-interested, craven, and—mostly importantly here—sloppy. They can’t hide anything. They make everything obvious. —Steve]

He then read Clarice Lispector’s An Apprenticeship or the Book of Pleasures (translated from the Portuguese by Stefan Tobler, edited by Benjamin Moser, 2022). [This was a recommendation from a friend, and a delightful one. It is aware that most works about romance are wish-fulfillment, and they have to be on account of the form and the demand for a happy ending. With this knowledge, it acknowledges its wish-fulfillment while also turning around and making demands of the reader. It is a story about a man who teaches a woman how to love, which is not perhaps so uncommon especially in fantasy, but he does so by forcing her to confront herself and figure out who she is and what she is capable of. Anyone familiar with the itch scratched by mediocre romantic comedies knows that we would vastly prefer the people we love to do this for us and make it easy. As Sheila Heti says in the afterword to my edition:

He can resist her, so he must be above her. And because she is below him, she is ready to make him her teacher. What does he hope to teach her? How to be worthy of him. Which is also how to be worthy of life itself—to be like rain, “without gratitude or ingratitude.”

This is an incredibly difficult task. It takes a great deal of patience to bring herself to that place, and she undergoes a lot of suffering—but also gains more illumination than many people find in a lifetime. Isn’t it horrible? What a plot! Yet can I say Lispector is wrong?

Love asks so much of us; it insists that we transform ourselves. The book’s emphasis on this and dedication to unveiling the process by which it happens makes it feel almost allegorical at times, as if Lóri (who frequently gets compared to various natural forces, most notably the sea) were the “natural” human being and Ulises (a professor of philosophy) were Love, or Philosophy, or something like that, demanding more of her. —Steve]

He then started reading Paradise Lost: A Primer (by Michael Cavanagh, edited by Scott Newstok, 2020).

Critical notes:

In Granta, Christian Lorentzen on the transitive “gift”:

I suspect but cannot prove—because I am no detective or expert in these matters but merely a crank or a buff with some rudimentary training and strong opinions that demand to be registered before the language acquiesces and finally accepts “to gift” like a child on Christmas morning, the wrapping paper in shreds on the rug and the receipt finally tossed in the bin, the point of no return, as it were, of linguistic commerce—that the resurgence of the transitive usage first took off from the coinage of “re-gifting,” merely a rumble in the language until the turn of the twenty-first century when it became not only permissible but practical (because, hey, why not?) to take something somebody gave you and give it on to somebody else, under a transparent veil of false pretenses, as if it isn’t the thought that counts because nothing really counts, especially at, say, an office holiday party or the birthday of an unbeloved cousin.

[Cranks have to stand together. Personally, I’ve given up on fighting the transitive “gift” even if I’ll never say it myself. What I will fight is the idea that “casted” is the simple past or past participle of “cast.” The life of an actor is full of enough indignities; must we add the additional indignity of being “casted” in parts? —Steve]