WRB—Oct. 29, 2022

Affirm: I am not going to apologize for how late this newsletter is.

So I bought me a ticket

I got on a plane to Spain

Went to a party down a red dirt road

There were lots of pretty people there

Reading the WRB

To do list:

order a tote bag or now a MUG;

avail yourself of our world-famous classified ads, now stored on this page for non-paying readers to access, either by placing or responding to one;

and,

Links:

The latest from The Atavist is good to read if you have all day.

Karl Ove Knausgaard on “Why the novel matters” at The New Statesman: “This is what the novel does: it pulls any abstract conception about life, whether political, philosophical or scientific in nature, into the human sphere, where it no longer stands alone but collides with myriad impressions, thoughts, emotions and actions. This is why Dostoevsky’s novels are still so eminently readable, the relationship between abstract ideas and a chaotic, bewildering, emotionally powered reality being their very rationale; Dostoevsky’s own ideals must submit in the event that an opposing voice belongs to a more interesting character. It’s also the reason why Lawrence’s novels aren’t nearly as good as Dostoevsky’s, for while Lawrence wanted the novel to be like life itself, the idea of life can become so powerful in his novels as to stifle what’s alive about them, life then losing its fluidity, its mutability, to solidify in the mould of thought.”

Adam Roberts with another look at Chapman’s Homer.

Reviews:

Dept. of Chris’ Preoccupations: For Book Post, Padgett Powell with a brief review of the LoA Barthelme volume (2021): “At the center of the cubist or impressionist or just abstract insult were these concrete moments of men or women in emotional delicacy. The business of emotion—’emotion of the better class, hard to come by,’ as he would put it to The Paris Review—was a preoccupation never not important to Barthelme. It was what could vindicate you of wacko mode. ‘All right. We have wacko mode. What must wacko mode do?’ we were asked one day when someone had tendered, I think, a dialogue between unnamed characters who were discussing, among other concerns and obliquely, a garter snake’s having eaten a Christmas bauble and having had a rough go because of the unhappy Yuletide ingestion.”

A bit late at this point but still interesting: For The Baffler, Nathan Shields reviews Jeremy Denk’s memoir of learning and playing piano very well (Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, in Music Lessons, March): “Given this gap between what classical music promises and delivers, why should we still think it makes life worthwhile? Denk’s answer comes, obliquely, in an episode toward the end of the book. He leaves his guru in Indiana to go to Juilliard. There he meets his ‘anti-Sebők,’ the famous violin teacher and ‘power broker’ Dorothy DeLay. Indifferent to ‘subtleties and shades, my many years of thought,’ she sees music as pure calculation and effect: ‘Well, it is the last movement, isn’t it? . . . And if you think about the audience, really, they need a new energy.’ What DeLay offers Denk is ‘the antidote to years of Bloomington idealism’: a vision of music demystified, in which the stagecraft is all that’s left. It feels ‘like a violence and a useful truth.’” [The Loser has been on my desk for months, maybe I’ll finally read it this weekend. —Chris]

[Julia, I know you just told me you don’t typically read all the links, but don’t skip this one. —Chris]: At the Genealogies of Modernity [Sigh. —Chris] blog, Charles Ducy reviews a recent novel by Tess Gunty (The Rabbit Hutch, August): “On its surface, then, Gunty’s novel takes on the form and content of its time with chameleon-like exactness. It is an impressive feat. But just as the chameleon’s transformation occurs superficially, this novel’s hypermodern dressings are a cover for something deeper. Even the brilliance of Gunty’s prose is not itself the novel’s beating heart. Gunty chooses her words—her adjectives especially—with precision. Midwesterners flash ‘supermarket smiles’ while mansions are perched on ‘sloping minty lawns.’ But perhaps greater attention is paid to the arrangement of morally fraught scenes, which frequently play in the wings of the main plot: one customer at a cafe refusing to yield an unoccupied chair; a grieving woman dodging her partner’s consoling embrace on a street corner; a boy casting his sister as an enemy on the playground; an apartment dweller invoking the golden rule as grounds for delivering a dead mouse to a neighbor’s doorstep. In contrast to the main conceits of the novel—the omnipresence of apps and devices, the pent-up sexual appetites, the vacillating perspectives—it is this human focus that gives The Rabbit Hutch its depth.”

N.B.:

Greater Greater Washington is looking for a managing editor.

D.C.’s hat lady died. R.I.P.

Working at the WRB is nothing like this in even one detail. [Working? —Nic]

Upcoming book:

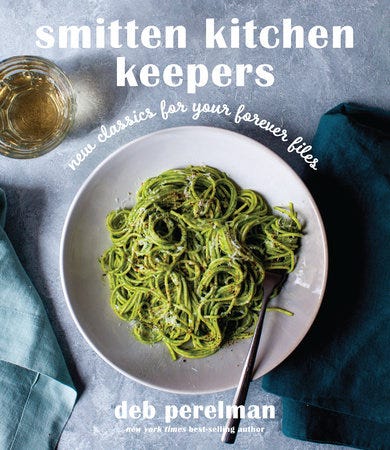

November 15 | Knopf

Smitten Kitchen Keepers

by Deb Perelman

From the publisher: Deb Perelman is the author of two best-selling cookbooks; one of the internet’s most successful food bloggers; the creator of a homegrown brand with more than a million Instagram followers; and the self-taught cook with the tiny kitchen who obsessively tests her recipes to make sure that no bowls are wasted and that the results are always worth the effort.

Here, in her third book, Smitten Kitchen Keepers: New Classics for Your Forever Files, Perelman gives us 100 recipes (including a few favorites from her site) that aim to make shopping easier, preparation more practical and enjoyable, and food more reliably delicious for the home cook.