WRB—Oct. 30, 2024

“it’s all intertextuality”

In that part of the Washington Review of Books of my memory before the which is little that can be read, there is a rubric, saying, Incipit Vita Nova.

N.B.:

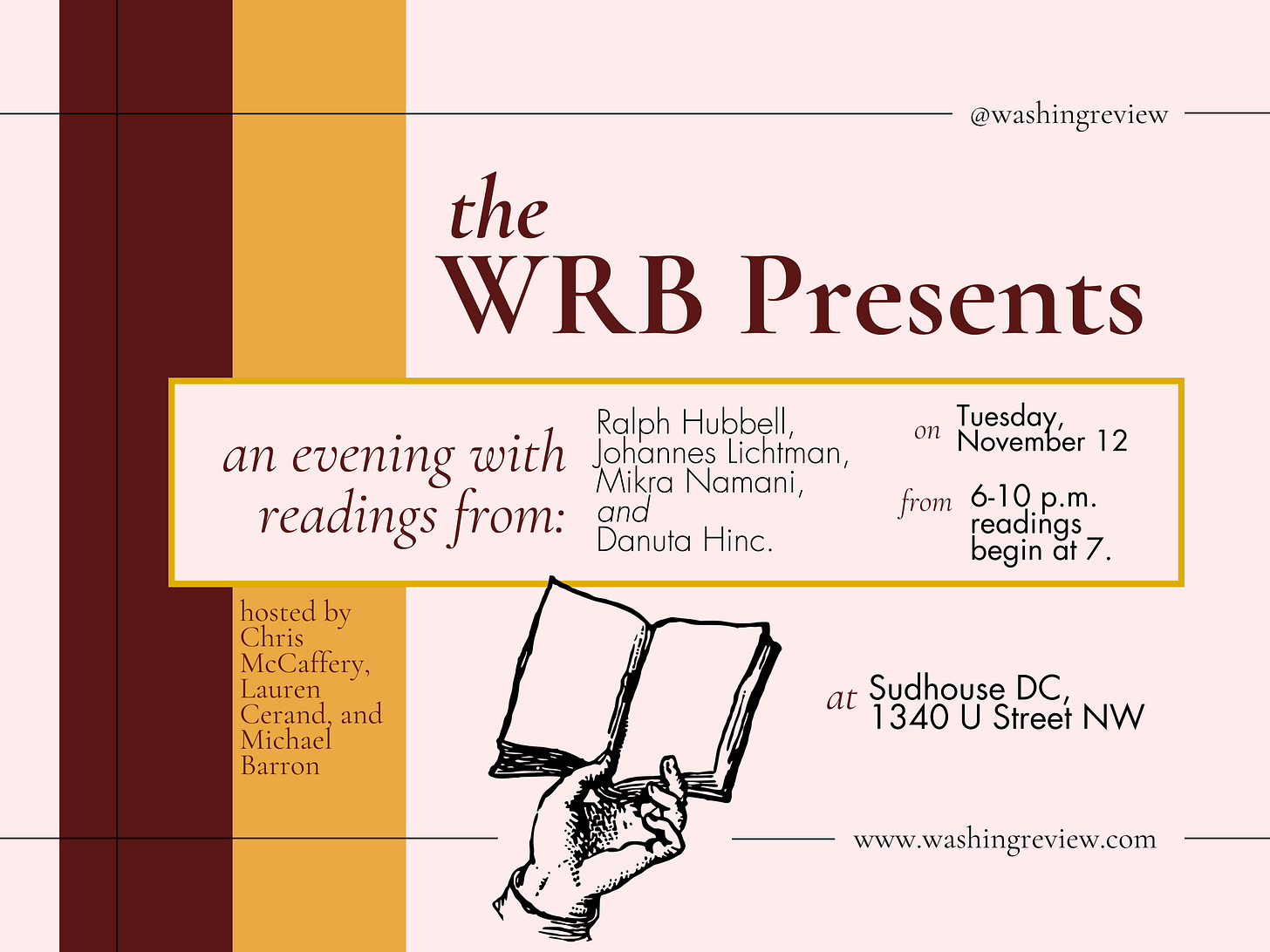

The next WRB Presents will take place on November 12, featuring Ralph Hubbell, Johannes Lichtman, Mikra Namani, and Danuta Hinc.

The audio of October’s D.C. Salon, on the topic “Is art more beautiful than nature?”, is now available:

Next month’s salon will meet on the evening of November 30 to discuss the topic, “Is order more important than justice?”

Links:

In the Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Diane Mehta on Dante’s friendship with Virgil in the Divine Comedy:

It is rare to have transcendent friendships that will break our hearts when we say goodbye. Virgil, for Dante, was like that. We all know that our parents will die and our children will leave. We are the children who leave and the parents who die. This is our lot, and our job. Dante wants to teach us how to say goodbye.

All through Purgatorio, Virgil warns Dante to stop looking back; we’re going to paradise, he’d say. The structure of the poem is designed around companionship, so it’s a shock to hear Dante keep driving home the fact that as we get older we have to learn how to leave the people we care about most. Dante meets people all the time, but there are only two friends in the poem. He bumps into his childhood friend Casella at the beginning of Purgatorio. Casella plays music and sings one of Dante’s love songs. What a good time—it’s just like being young and in Florence again. Dante asks Casella if he loves him and Casella says yes, I loved you in my mortal body and I love you now. It is painful to watch them say goodbye, but the loss of Casella is only a hint of the greater loss to come. So often during the journey, Dante casts Virgil in a parental role so that we recognize how it will feel when Virgil leaves.

[I think two is an undercount—maybe people with other roles in relation to Dante were left out. But to insist that, say, Brunetto Latini was not Dante’s friend because he was his teacher would be to misunderstand what it means to be a friend and a teacher.

Dante’s friends also play important roles in La vita nuova, in which there are three moments that transform his poetry. The first happens when a friend, hoping to cheer Dante up, decides to take him to see all the pretty women at (what I, along with the note in my NYRB edition, can only conclude is) Beatrice’s wedding feast. Needless to say, this doesn’t work at all, but the experience forces Dante to rethink how he imagines his poetry. The second comes when some women he is friends with express their judgment of his work, telling him that, if he were sincere about wanting to praise Beatrice, his poetry would be doing that instead of recording his moping around. And the last comes with the death of Beatrice, which is the death of a friend and a friendship (after a fashion) in this life. Dante is a poet of friendship, not least because of his openness about the influence of his friends on his work. Even the Comedy, a poem of exile, is a poem about where his friends went—the ones he meets in it are all dead— and what they meant to him, and Virgil, through his poetry, is a friend Dante will always have with him.

Are we losing this? Brandon Taylor, in a piece on Sally Rooney:

I spent a lot of the summer reading European, British, and Irish novels by contemporary authors, some debuts, some established, but it was only when I read a recent American novel that I realized that the key difference between the Euro-British-Irish novel and the novel of the United States at just this moment is that characters in novels by American writers don’t have any friends. I don’t know how I didn’t notice it before. One of the significant drivers of plot and theme in Rooney’s work—like that of her European contemporaries—is hanging out and all that it entails. Her characters exist in large networks of friendships, neighbors, families, family friends, coworkers, old lovers, roommates, and more.

As an American who has friends, maybe I need to write a novel.

“It is rare to have transcendent friendships that will break our hearts when we say goodbye” is a sad sentence. It’s only as rare as you make it—any friendship is a giving away of part of yourself, and part of living is giving most of yourself away. I have little idea who I am outside of my friendships. The loss of any of them is a wound, even if it happens through the natural and inevitable process of falling out of touch. If we don’t experience it as devastation it is only because we are too small, too limited in time and space, full of too many other cares.

In spite of all we hear about the alienating effects of technology, I want to say that letting me talk to any of my friends near-instantly has made me even closer to them. (And it has allowed me to make friends I never would have otherwise.) Yes, it prevents some falling out of touch, but the ability to put down any thought and send it immediately has led to my thinking transforming from something that happens in my own head into something that happens collaboratively in texts and Instagram DMs and emails. (To those whose texts and Instagram DMs and emails are full of very rough drafts of comments that appear in the WRB: thank you.) And to lose that is a kind of heartbreak. It feels like having part of your brain removed, like having part of your body amputated. As Dante understood, loving your friends is bound up in being seen, being challenged, and being transformed by them, and missing them is missing that experience. —Steve]

In Lithub, an excerpt from Damion Searls’ new book on translation (The Philosophy of Translation, October 29) [An Upcoming book in WRB—Oct. 26, 2024.]:

I will begin with, but quickly abandon, the nearly universal and often unexamined image of translation as bringing an original text from one language into another. This is an image of two isolated villages or islands, separated by some kind of gap, with no contact between them except that lone, special, unusually mobile person, the translator, who is able to bring messages from one place to the other, maybe even occasionally smuggle in some food. Although this is sometimes the right way to talk about translation, it usually isn’t. It creates all sorts of false dichotomies, mischaracterizes what translators actually do, misrepresents the continuities between translation and other kinds of writing, and misunderstands the nature of reading.

Reading—“this fruitful miracle of communication in the bosom of solitude,” as Proust called it in a translator’s preface—is miraculously and mysteriously neither objective nor subjective, neither purely taking something in nor purely revealing or expressing what’s inside oneself. It is a complex interplay of the self and the world, analogous to perception—we see what’s really there in the world, but we see it, and it’s there in our world, the environment we move in and care about, which is different from the environment of any other person or animal in the same physical space.

[Behind the paywall: Grace on a poem by A. A. Milne, Steve does his usual bit about the novel, explains why Dante and Milton are like that, and quotes the Beatles; also included below are beer, being online, Mormonism, Auden, Cheddar, lady detectives, and more links, reviews, news items, and commentary carefully selected for you, just like on Saturdays. If you like what you see, why not sign up for a paid subscription? The WRB is for you, and your support helps keep us going.]